By CATHERINE SABISTON, PH.D., AND ROSS E. ANDERSEN, PH.D.

About one-third of women will develop some type of cancer in their lifetime. Breast cancer is the most common cancer globally, accounting for 17.9 percent of all diagnoses. The National Cancer institute estimates that 12.2 percent of women born today will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point in their lives (National Cancer Institute, 2011).

Have you trained women after they have undergone treatment for breast cancer? Share your experiences and training tips in the comments section below.

Rates of breast cancer increase rapidly as women age through the childbearing years. Risk factors for breast cancer include aging, beginning menstruation at an early age, late menopause (after age 55 years), a family history of disease, genes, age of parity, and excess weight gain. Alcohol consumption and a high-fat diet may also increase the risk of breast cancer, while an active lifestyle is associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer (Kohl, Laporte and Blair, 1988). The good news is that breast-cancer survivorship has improved dramatically in recent years and many survivors are leading long, healthy lives. In fact, death rates from breast cancer decreased 37 percent between 1990 and 2005 (Jemal et al., 2009).

The American Cancer Society has added an active lifestyle to their list of ways to reduce the risk of cancer. Appropriate exercise also can play a crucial role in helping breast-cancer survivors improve their quality of life and well-being, while also helping to reduce the risk of recurrence (Harrison, Hayes and Newman, 2010). Unfortunately, breast-cancer survivors tend to be more overweight and sedentary than women who have not experienced the disease. The most striking finding from a review on physical activity, diet and adiposity in breast-cancer survivors was that obesity was associated with a 30 percent increased risk of mortality (Courneya, Katzmarzyk and Bacon, 2008). Moreover, an active lifestyle was associated with a 30 percent decreased risk of mortality. Thus, new strategies are needed to help breast-cancer survivors live healthier, more active lives.

Taking Advantage of a “Teachable Moment”

The completion of primary treatment for breast cancer (i.e., surgery, radiation and/or chemotherapy) has been referred to as a “teachable moment” for health-behavior change such as starting an exercise program. Specifically, women may be more receptive and responsive to receiving physical-activity recommendations during the survivorship period. Unfortunately, an estimated 58 percent of breast-cancer survivors are not sufficiently active to gain health benefits (Courneya, Katzmarkzyk and Bacon, 2008). While there are myriad reasons for these high rates of inactivity, many survivors confess to feeling overwhelmed and unsure of how to begin an exercise program, and the pressure of gaining or maintaining a healthy lifestyle may add to the stress they already face. Therefore, it is critical that they are educated about the importance of adopting a physical-activity program, sooner rather than later. There is evidence to suggest that, independent of a woman’s activity level prior to breast cancer, changes in physical activity post-diagnosis lead to important health gains (Blanchard, Courneya and Stein, 2008). Therefore, barring any restrictions imposed by a physician, there is no better time to help breast-cancer survivors design and implement physical-activity programs.

Surveys of oncologists reveal that time constraints or uncertainty regarding the accuracy or appropriateness of offering certain lifestyle and behavioral recommendations often prevent them from discussing the importance of exercise with their patients (Jones et al., 2005). Therefore, cancer survivors may be considered optimal candidates for exercise and lifestyle counseling and intervention. In addition, many medical professionals are eager to refer their patients to competent fitness professionals. As a fitness professional, you can help survivors make the most of their “teachable moment,” when they are most likely to follow instructions and do their best to make healthy lifestyle choices.

Physical-activity Guidelines for Breast-cancer Survivors

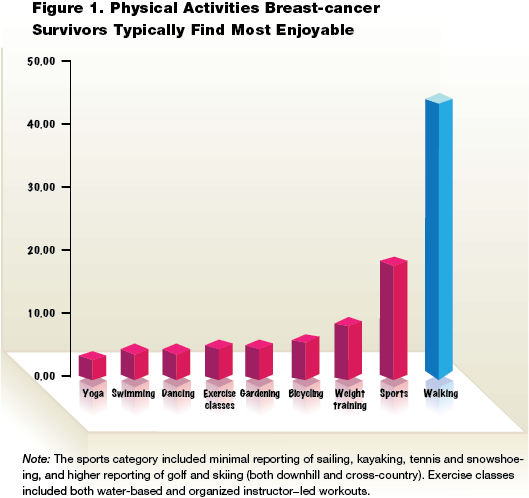

Physical-activity guidelines suggest that breast-cancer survivors should engage in aerobic activities at moderate intensity for a total of 150 minutes per week or vigorous/strenuous intensity for 75 minutes per week; or some combination of moderate and vigorous activities (Schmitz et al., 2010). Most survivors appear to enjoy cycling and/or walking as their primary activities—it is always best to make sure your clients are participating in activities that they enjoy. In a research project that is underway at McGill University, breast-cancer survivors were asked to identify the activity about which they are most passionate. More than half of the sample (163 women to date) reported a physical activity as their most passionate activity (Figure 1).

Recommendations for strength training include performing activities that work the major muscle groups in both the lower and upper body two or three times per week. To improve flexibility, recent recommendations suggest stretching major muscle groups when aerobic and strength-training activities are performed. These guidelines are similar to those established for the general adult population, and have been deemed safe, feasible and effective by a large consortium of physical activity and oncology experts (Haskell et al., 2007).

Actual Quotes from Participants in the McGill University Study of Exercise and Breast Cancer

“It’s hard to explain. I’m doing things in the last few months that I wouldn’t have believed I could’ve done last year…I’m lifting things easier than I did before…picking up a jug of milk takes less effort…I open doors, hold doors…I pick my cat up… I can lift things that I wouldn’t have lifted before.”

–63-year-old breast-cancer survivor, speaking on the benefits of exercise

“It’s been something beyond my wildest expectations really…pushing myself physically, I feel great. I’ve accomplished things that I never thought possible at my age…No kidding. It’s really empowering…I just feel so pumped.”

—56-year-old breast-cancer survivor

“I have muscles. I didn’t expect to have muscles. I am 58 years old and I love being cut!”

—breast-cancer survivor

“I now know the importance of physical activity and all of its benefits, and how it has such a large effect on my life. I have taken back control over my emotions, and I have re-discovered the body I once had. It is an extraordinary feeling to be a survivor of breast cancer, but it’s even more extraordinary to have more and more energy to accomplish.”

—33-year-old breast-cancer survivor

“I am losing weight, but not because of how I look to others—I want to be in the best shape and form that I can be as I continue on the path of survivorship and aging.”

—62-year-old breast-cancer survivor

Summary of the Benefits of Physical Activity

Physical activity at or less than the recommended levels has many physiological, psychological and social benefits for breast-cancer survivors. Most importantly, physical activity may protect breast-cancer survivors from premature death and/or death due to their cancer (Sternfeld et al., 2009; Irwin et al., 2008). From a physiological or biological perspective, physical activity may be associated with improved immune function, reduced fatigue and cancer-related fatigue, protection from the loss of bone mass (a frequently reported concern among breast-cancer survivors), improved sexual functioning, reduced incontinence, improved sleep, reduced pain, improved balance, and reduced blood pressure and resting heart rate. Physical activity is also clearly and consistently linked to improved cardiorespiratory fitness, and favorable changes in body composition including reduced fat mass and increased lean-body mass. An active lifestyle may also help survivors improve their quality of life, with the strongest effects noted in the physical health (the control/relief of symptoms, maintenance or improvement in biological and physiological indicators of health, co-morbidities), functional health (the maintenance of function and independence, balance), and mental health (cognitive and affective aspects including emotional distress, fear of recurrence and death, body image and self-esteem) (Schmitz et al., 2010; Courneya, 2003; Speck et al., 2010).

From a psychological perspective, physical activity is an effective mechanism for reducing the burden of mental illness among cancer survivors (Massie, 2004; Stark and House, 2000). Lower levels of depression and anxiety are consistently demonstrated as outcomes of physical activity, as well as improved mood and lower levels of stress. There is also a possible association between engaging in physical activity and experiences of posttraumatic growth. Specifically, physical activity may provide opportunities to experience a new appreciation for life, relate to others, realize new opportunities and gain personal strength (Sabiston, McDonough and Crocker, 2007). Furthermore, physical activity is linked to improvements in several body-image constructs such as self-esteem, physical self-perceptions and reduced anxiety (Pinto and Trunzo, 2004). Finally, other benefits of active living may include enhanced happiness, sexual attractiveness, personality and locus of control, and reduced tension, cognitive disorganization, emotional irritability and confusion.

From a social perspective, group- or community-based programs targeting women, either during or following treatment, may foster increased feelings of social support and connectedness among breast-cancer survivors. The evidence suggests that group activity is beneficial in helping breast-cancer survivors gain support by providing them with a forum to discuss cancer-related (and non-cancer-related) concerns within a group of “similar others.” In fact, some women describe the benefit of receiving social support during exercise programs as more desirable than that obtained in support groups. Specifically, the women feel they get the informational, emotional and role-modeling support they need, and there is more of a focus on achieving and challenging oneself physically rather than what one breast-cancer survivor described as “too much navel-gazing” (Sabiston, McDonough and Crocker, 2007).

It is important to consider the type of treatment that each woman has endured before designing a physical-activity program. Each treatment, and the period of time since various treatments have ended, is associated with a range of considerations that need to be incorporated into the exercise program. In addition to the information provided in Table 1, it is also important to consider the age of the individual and whether she has any comorbidities or predisposing factors that could influence her ability to engage in exercise. Be sure to follow age-specific exercise protocols. Finally, it is also important to consider that some women may have unique needs for physical activity. For example, some women may choose not to exercise in front of mirrors; others might prefer a home-based or small group-based environment. Women engage in more physical activity if they enjoy it and feel competent in achieving their goals. For this reason, walking and other lower-intensity activities may initially be preferred to more vigorous exercise. And while individuals who were active before their diagnosis will likely have more confidence and will be more comfortable exercising vigorously, those who have been largely sedentary will likely need more help, attention and compassion to get their programs underway (Christmas and Andersen, 2000).

Workout attire is another important consideration for helping women enjoy exercise, and clients should be encouraged to choose clothing that makes them feel comfortable. Some women who have lost their hair due to chemotherapy may prefer to wear a wig rather than a headscarf, even though this may increase their sensitivity to heat and possibly limit the type of exercise they can do. Creating and maintaining a training environment that is comfortable, cool, provides water stations or breaks, and that limits social and/or personal comparison (i.e., no mirrors, no sections where other exercisers can watch) is most conducive to an effective physical-activity program, particularly for breast-cancer survivors who are new to exercise.

Conclusion

Recent advances in the detection and treatment of breast cancer has led to an increased number of breast-cancer survivors in the U.S. and around the world. Survivors are often eager to make positive changes in their lifestyle, but may feel overwhelmed with the prospect of starting an exercise program and uncertain about how and where to begin. Compassionate fitness professionals can become important members of the healthcare team in helping breast-cancer survivors improve their physical and emotional quality of life, while also reducing the risk of recurrence. For more education on working with clients who have cancer, see ACE's online continuing education course Cancer and Exercise.

References

Blanchard, C.M., Courneya, K.S. and Stein, K. (2008). Cancer survivors' adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: Results from the American Cancer Society's SCS-II. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26, 13, 2198–2204.

Christmas, C. and Andersen, R.A. (2000). Exercise and older patients: Guidelines for the clinician. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 48, 3, 318–324.

Courneya, K.S., Katzmarzyk, P.T. and Bacon, E. (2008). Physical activity and obesity in Canadian cancer survivors: Population-based estimates from the 2005 Canadian Community Health Survey. Cancer, 112, 11, 2475–2482.

Courneya, K.S. (2003). Exercise in cancer survivors: An overview of research. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 35, 11, 1846–1852.

Harrison, S.A., Hayes, S.C. and Newman, B. (2010). Age-related differences in exercise and quality of life among breast cancer survivors. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 42, 1, 67–74.

Haskell, W.L., et al. (2007). Physical activity and public health: Updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39, 8, 1423–1434.

Irwin, M.L., et al. (2008). Influence of pre- and postdiagnosis physical activity on mortality in breast cancer survivors: The health, eating, activity, and lifestyle study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26, 24, 3958–3964.

Jemal, A., Siegel, R., Ward, E., Hao, Y., Xu, J. and Thun, M.J. (2009). Cancer statistics, 2009. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 59, 4, 225–249.

Jones, L.W., Courneya, K.S., Peddle, C. and Mackey, J.R. (2005). Oncologists' opinions toward recommending exercise to patients with cancer: A Canadian national survey. Support Care Cancer, 13, 11, 929–937.

Kohl, H.W., Laporte, R.E. and Blair, S.N. (1988). Physical activity and cancer: An epidemiological perspective. Sports Medicine, 6, 4, 222–237.

Massie, M.J. (2004). Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs, 32, 57–71.

National Cancer Institute. (2011). Probability of Breast Cancer in Women.

Pinto, B.M. and Trunzo, J.J. (2004). Body esteem and mood among sedentary and active breast cancer survivors. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 79, 2, 181–186.

Sabiston, C.M., McDonough, M.H. and Crocker, P.R. (2007). Psychosocial experiences of breast cancer survivors involved in a dragon boat program: exploring links to positive psychological growth. Journal of Sport Exercise Psychology, 29, 4, 419–438.

Schmitz, K.H., et al. (2010). American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 42, 7, 1409–1426.

Speck, R.M., et al. (2010). An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 4, 2, 87–100.

Stark, D.P. and House, A. (2000). Anxiety in cancer patients. British Journal of Cancer, 83, 10, 1261–1267.

Sternfeld, B., et al. (2009). Physical activity and risk of recurrence and mortality in breast cancer survivors: Findings from the LACE study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 18, 1, 87–95.

________________________________________________________________________

Dr. Catherine M. Sabiston is an assistant professor of exercise psychology at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec. Her research interests are focused primarily on the link between indicators of emotional wellbeing and physical activity motivation and behaviour. Her studies target individuals who are most at-risk for low levels of physical activity, including women, individuals with chronic disease, and youth.

Dr. Ross E. Andersen is the Canada Research Chair in Physical Activity and Health at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, where he is a professor in the Departments of Kinesiology, Medicine and Nutrition. He was a contributor to the ACE Clinical Exercise Specialist Manual and served on the ACE Board of Directors for eight years.