By Megan Senger

Personal trainers often give clients cues on how to move the shoulder blades during back- and chest-strengthening exercises. But they rarely agree on exactly how trainees should do so in the case of exercises like push-ups or lat pull-downs. Should the shoulder blades retract mostly at the beginning of the exercise? Retract throughout the exercise? Protract throughout? Or just move freely?

This article examines shoulder-blade positioning during four common resistance exercises, and explains when, why and how you should cue scapular movement to help your clients achieve safe and effective form.

Moving Naturally

Generally speaking, a client’s shoulder blades should be allowed to move “naturally” during pushing and pulling exercises, says Rick Kaselj, M.S., a Surrey, British Columbia−based kinesiologist, ACE-certified Personal Trainer and creator of the fitness blog ExercisesForInjuries.com. Natural movement, Kaselj explains, means “the scapulae are moving in a smooth and controlled manner into retraction.”

However, for those with known shoulder-girdle imbalances, the “right” way to move will depend on the exercise objective and your level of expertise in assessing scapular function. For novices and those with known shoulder dysfunction derived from injury, chronic pain or prior medical treatment(s), you should clarify cues before movement begins, says Irv Rubenstein, Ph.D., an author, exercise physiologist and president of STEPS, Inc., a personal-training center in Nashville, Tenn.

Anatomical Review

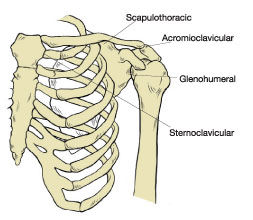

The shoulder girdle is made up of the clavicles (collar bones) and scapulae (shoulder blades.) The upper and outer bony edge of each shoulder blade is a protrusion known as the acromion process. Although the acromion is part of the scapula, your clients may think of it as their “shoulder bone.”

The scapulae “float” or “glide” over the soft tissues on the posterior (back) side of the upper (thoracic) ribcage, forming the scapulothoracic joint. It is not a true joint, anatomically speaking, because it does not have typical articular characteristics such as a ligament capsule or a meeting of bony surfaces. Nevertheless, it plays a critical role in movements of the shoulder and upper arm.

The glenohumeral joint is the articulation between the head of the humerus (upper arm) and the glenoid fossa of the scapula (the concave “socket” on the upper outside corner of each shoulder blade). Scapulohumeral rhythm refers to synchronous motions of the glenohumeral and scapulothoracic joints that coordinate full elevation of the arm.

To start, consider the client’s goals: A bodybuilder and a sedentary office worker with poor posture clearly have very different needs. “If the goal of the exercise is to build muscle size in one area of the body versus to correct a musculoskeletal imbalance, then the motion of the scapula can be coached or the exercise manipulated differently,” says Justin Price, M.A., a corrective exercise specialist, creator of The BioMechanics Method and an ACE-certified Personal Trainer based in San Diego, Calif.

Above all, proceed with caution. Poorly cued exercises involving the shoulder girdle can lead to unnatural, inefficient movements outside of the gym, explains Paul Chek, H.H.P., N.M.T., founder of the CHEK Institute and a corrective exercise specialist based in San Diego, Calif.

To ensure efficient scapular motion, consider the following:

Manage the weight. “Don’t overload the movement at the expense of form,” says Rubenstein. Sacrificing form for load results in what he calls a “bad neuro-education” and teaches faulty movement patterns. “As [the weight] exceeds the client’s functional range of loading, there will be secondary (compensatory) movements induced, such as bobbing of the head, hiking of shoulders or overuse of the back,” notes Chek.

Consider the ribs. “I place emphasis on first aligning the ribcage to create a good platform for the scapula to glide upon, and then work on the timing and coordination of scapular motion,” says Price.

Check the neck. During each exercise the head should be in neutral, Kaselj says. “If the head is dropped, the scapulae will elevate as the upper trapezius becomes more involved in the movement,” he explains.

Use neutral spine…usually. “Neutral spine is good for many exercises, but not all,” notes Rubenstein. For example, “during reverse flys you actually get better movement if you go a little into extension of the spine,” he says.

Consider these principles as you cue the following pushing and pulling exercises:

Low Rows

Healthy Movement: “The scapula should [protract] and outwardly rotate as the arm reaches forward,” explains Price. “As the arms pull the weight back [during the concentric phase of the exercise] the scapulae should retract and inwardly rotate back to the starting position.” Scapular movement will change slightly as the arm raises or lowers, or if the width of the grip is altered, Price adds.

Cueing Correctly: Watch out for overactivation of the upper trapezius (seen as a raising or shrugging of the shoulders during the exercise), says Rubenstein. Verbally cue clients to move the shoulder blades “back and down,” and to raise the sternum up during the concentric phase of the row.

Avoiding a Bad Neuro-education: Rubenstein feels many trainers overemphasize pre-movement scapular retraction. “If the shoulder blades go back [i.e., retract] too soon, you’re retraining the client’s shoulder blades to move before the humerus moves. That would be detrimental to real-ife and/or sports-specific scapulohumeral rhythm,” he says.

Lat Pull-downs

Healthy Movement: “The scapulae should outwardly rotate and elevate as the arms reach upward,” says Price. “As the arms pull the weight back down, the scapulae should inwardly rotate and depress back to the starting position.” Price notes that this pattern may include some retraction/protraction and anterior tilt if cables are used instead of a pull-down bar.

Cueing Correctly: As with low rows, Rubenstein cues clients to move the shoulder blades “back and down,” and avoids cuing for bar movement. If told to “bring the bar to the chest,” weaker or more inflexible clients will usually roll the shoulders internally and elevate the elbows, he says. Instead, trainers should say, “bring the bar down by pulling your elbows toward your ribs and back, and stick your sternum up to the bar,” Rubenstein counsels, noting that this also moves the lumbar spine into an ideal, lordotic position.

Additionally, Kaselj advises clients to avoid relaxing and elevating (i.e., shrugging) their shoulders at the top of the movement. This prevents both the overactivation of the upper trapezius and excess compression on the structures between the head of the humerus and clavicle.

Avoiding a Bad Neuro-education: As with rows, do not cue strong scapular retraction and depression at the beginning of the pulldown (i.e., prior to concurrent movement at the glenohumeral joint), says Kaselj. “When you start the exercise by moving your shoulder blades down and together [prior to upper-arm movement at the glenohumeral joint] you affect the proper movement pattern of the scapulae and scapular muscles,” he explains. “The muscles around the scapulae should be active prior to the movement, but the contraction should be at a level that the scapulae can still move freely during the full exercise.”

Reverse Flys

Healthy Movement: The scapulae should [protract] as the arms come across the body and the weight lowers, says Price. “As the arms pull the weight back in line with the shoulders [i.e., the weight is lifted], the scapulae should retract.” Price notes that scapular movement will change slightly if the position of the arm or grip position is altered.

Cueing Correctly: Spinal position is important for smooth scapular movement during this exercise, Rubenstein explains. In particular, a lordotic curve should be maintained to help the shoulder blades move properly on the thoracic ribcage, he says.

For reverse flys to be effective with dumbbells, the client’s torso needs to be parallel to the floor so the arms can move through true horizontal abduction, he adds. “If the client’s torso is at an angle, you won’t get the ‘down’ part of the back and down [of shoulder blade retraction during the concentric phase of movement].”

However, when using tubes or cables in an upright position, cue clients to “raise the chest up” and pull the shoulder blades back and down during the concentric phase of the exercise, he says.

Avoiding a Bad Neuro-education: Trainers should cue for shoulder-blade movement (“back and down”) versus only movements of the hand (“raise the weight up”), Rubenstein says. This ensures that motion occurs at the shoulder blades as well as the glenohumeral joint.

Push-ups

Healthy Movement: “The scapulae should retract and slightly inwardly rotate (depending on how wide the hands are placed apart) on the down phase of the push-up,” explains Price. “As the arms push away from the body, the scapulae should protract and slightly outwardly rotate.” Price adds that scapular movement will change if arm or hand positions are altered.

Cueing Correctly: To avoid interfering with the natural movement of the shoulder blades, Kaselj keeps it simple. “The only cue that I give my clients is to activate the muscles around the scapulae,” he says. “If they have elevated shoulder blades or overactive upper-trapezius muscles, I will cue them to lightly depress the scapulae.”

Avoiding a Bad Neuro-education: Be cautious when entering what Rubenstein calls the high-risk range of the push-up movement—the lowest part when the chest is closest to the floor, the shoulder blades are retracted, and the pectoral muscles and triceps are targeted. Rubenstein argues this can be inappropriate for a client who is weak or has a history of shoulder problems.

In the lowest part of the push-up, “you’re essentially ‘hanging on’ with the serratus anterior, which is then working in a stretched position,” Rubenstein says. “Hence, the serratus doesn’t strengthen or learn to bring the blades forward as it should in scapular protraction,” thus interrupting healthy motor patterns of the serratus and shoulder blades.

Another controversial way to target the pecs is to hold the shoulder blades in retraction during chest exercises. “Bodybuilding lore has people bench press or perform a push-up by holding the shoulder blades in retraction to eliminate the serratus anterior function of scapular protraction. This creates a greater demand on the pecs to bring the humerus into horizontal flexion,” explains Rubenstein. “This may serve a purpose if bodybuilding, [but] if lifting for function, it’s totally inappropriate” because it teaches the nervous system unnatural muscular sequencing.

Movement Review

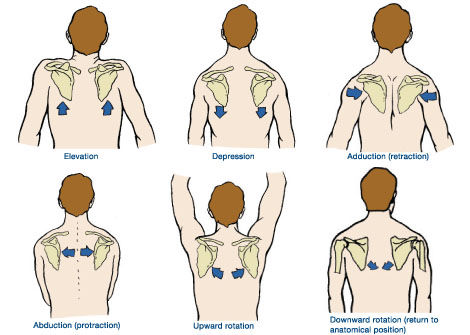

Biomechanics expert Justin Price shares his “very basic definitions” of seven shoulder blade movements below. Note that, in practice, scapular motions are nonlinear and do not occur in isolation. Thus, any given movement typically includes two or more of the following:

Elevation: When the scapula moves upward on the ribcage (i.e., shoulder shrug)

Depression: When the scapula moves downward on the ribcage

Adduction or Retraction: When the scapula moves toward the spine

Abduction or Protraction: When the scapula moves away from the spine

Upward rotation: When the bottom corner edge of the shoulder blade rotates up and away from the spine (i.e., lateral or upward rotation)

Downward rotation: When the bottom corner edge of the shoulder blade rotates down and in toward the spine (i.e., medial or downward rotation)

Anterior tilt (not depicted): When the top edge of the scapula tilts down and forward, and the bottom edge lifts up and away from the ribcage

Instructing Overall Movement

Keeping these details in mind, you should still be very cautious when assessing the health of a client’s current scapular-movement patterns. “If you do not have the specific skills to assess motor sequencing in the human body, it is much better to simply train the individual to use their body naturally,” says Chek. “For example, you will never find a monkey or chimp climbing a vine prematurely adducting [i.e., retracting] their scapula as part of a pulling sequence while climbing a vine.”

When in doubt, leave the refinement of musculoskeletal imbalances to physical or occupational therapists and simply teach gross motor skills emphasizing natural, fluid movements in the shoulder girdle area.

____________________________________________________________________

Megan Senger is a writer, speaker and fitness sales consultant based in Southern California. Active in the exercise industry since 1995, she holds a bachelor’s degree in kinesiology and English. When not writing on health and lifestyle trends, techniques and business opportunities for leading trade magazines, she can be found in ardha uttanasana becoming reacquainted with her toes. She can be reached at www.megansenger.com.