By Todd Galati, M.A.

Shoulder instability is very common and has many causes. Before you can design an exercise program to help your clients with shoulder instability, you must first understand shoulder structure and function, common causes of instability and potential injuries. Armed with this knowledge, you can make better decisions about the functional issues that can be addressed through a fitness program, appropriate movement assessments and resultant exercises, and when to refer.

Shoulder Structure and Function

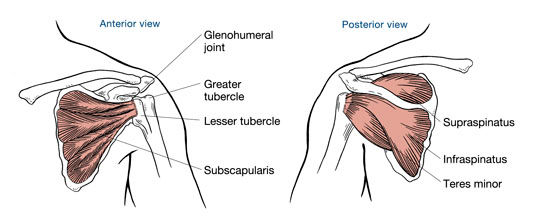

At the root of shoulder instability is its structure. The shoulder joint is a shallow ball-and-socket joint that is formed by the attachment of the head of the humerus with the glenoid fossa of the scapula. The glenoid labrum provides a bit more depth to the glenoid fossa’s “socket,” while the ligaments, joint capsule and rotator cuff muscles collectively hold the shoulder joint together. The scapula is then attached to the torso via a two-joint linkage formed by the scapula’s attachment to the clavicle at the acromioclavicular joint and the clavicle’s attachment to the sternum at the sternoclavicular joint. These connections are given dynamic support from the scapulothoracic joint formed by the muscles that originate on the torso and insert on the scapula and humerus (e.g., trapezius, latissimus dorsi). These combined structures form the shoulder complex, a highly mobile unit that allows greater range of motion and increased velocity when throwing or striking.

When the shoulder complex is functioning properly, it has pain-free mobility built upon a stable scapula. Scapular stability is essential for programs focused on improved shoulder function, mobility and strength. The scapula is mobile, adding to the full range of motion of the shoulder complex; however, its primary design is to serve as a stable platform from which the shoulder moves the upper limb. When the muscles that act on the scapula are weak, they compromise scapular stability. In her book, Therapeutic Exercise for Musculoskeletal Injuries, Peggy Houglum describes the difference between a stable and an unstable scapula for the shoulder as being “similar to the difference between running on firm ground and running on a suspended wood-and-rope footbridge.” In this analogy, the firm ground provides a stable base for propulsion, while the unstable footbridge “places high energy demands on the individual’s leg muscles, causes incoordination and inefficiency of movement, and increases risk of injury” (Houglum, 2005). As with this footbridge example, an unstable scapula will transfer its instability to the shoulder joint, causing movement issues and increased risk of injury.

The bones, articulations and ligamentous structures provide static stability for the shoulder complex, while the muscles and nervous system provide dynamic stability. Static stability of the shoulder can be compromised by injuries to the ligaments (e.g., shoulder separation), bones (e.g., fractured clavicle) or tightness in the joint capsules. Injuries to the ligaments or joint capsule can impair the normal proprioceptive function of the neural receptors in the injured ligaments, which can inhibit the response of the muscles. Dynamic stability can also be compromised by injuries (e.g., biceps tendinitis), shoulder impingement or an imbalance in the muscle force couples acting on the scapula.

Scapular instability can cause the glenohumeral joint to migrate superiorly, which can lead to shoulder impingement and biceps or rotator cuff tendinitis (Houglum, 2005). Other factors that can negatively impact shoulder stability and function include postural deviations that change the mechanics of the shoulder complex (e.g., scapular protraction due to exaggerated kyphosis) and the stability-mobility relationship of other joints in the kinetic chain. For example, a baseball player with limited thoracic spine mobility will have to rely on increased mobility in the lumbar spine and scapulothoracic joints to allow his hand to travel the arc and speed needed to make a particular throw. This change in mechanics due to a tight thoracic spine can lead to injury.

Regardless of the cause of a client’s shoulder instability, the exercise program should focus primarily on stabilizing the scapula. This will provide the foundation for proper movement and balance within the shoulder complex, and will significantly reduce the risk of injury. It is important to remember that any client experiencing pain during assessments or exercise should be referred to his or her physician for evaluation.

Assessments

After performing a thorough health history to rule out any current pain, injuries or risk factors requiring referral to a physician for evaluation, your next step is to conduct a basic postural screening to look for pronounced deviations from normal posture. Key postural deviations that can directly impact shoulder function include exaggerated kyphosis, protracted scapulae, medially rotated humerus, elevated shoulders and any asymmetry among shoulder positions. Exaggerated kyphosis has become more commonplace due to increased computer use in both the workplace and at home. This postural deviation can limit movement in the generally mobile thoracic spine, causing the adjacent links in the kinetic chain—the scapulothoracic joint and lumbar spine—to compensate for the inhibited thoracic spine mobility. This chain of events can eventually lead to decreased stability of the scapulae and lumbar spine, setting up both the shoulder and the lower back for potential injuries. The other postural deviations at the shoulder can take the scapulae out of normal alignment, which can alter shoulder mechanics, setting it up for instability issues and increased risk of injury.

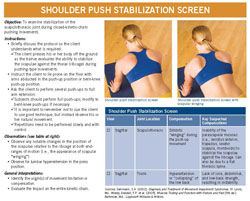

After noting any key postural deviations, the next step is to assess shoulder stabilization and thoracic mobility. The shoulder push stabilization screen is relatively easy to implement and provides feedback about the client’s ability to stabilize his or her scapulae while performing a push-up (modified as needed to bent-knee or even wall push-up, dependent upon the client’s current fitness). Any observable scapular instability should be noted, such as the medial borders of the scapula lifting up away from the torso (scapular “winging”), which would indicate weakness in the muscles controlling the scapulae; it can also be caused, to a degree, by a flatter-than-normal thoracic spine. The thoracic spine mobility screen will provide data about the client’s ability to rotate the trunk to each side, with 45 degrees being the benchmark for adequate rotation. The protocol for the shoulder push stabilization screen can be accessed by clicking on the image to the right, while the thoracic spine mobility screen can be found in Chapter 7 of the ACE Personal Trainer Manual (4th edition).

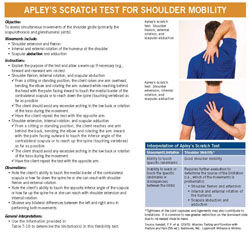

To assess range of motion of the shoulder, have the client perform all or a combination of the following tests:

- supine shoulder flexion

- prone shoulder extension

- supine internal and external rotation

- Apley’s scratch

Each test provides feedback on the client’s mobility in different planes of motion. The protocol for Apley's scratch test can be accessed by clicking on the image to the right, while the protocols for the other three assessments can be found in Chapter 7 of the ACE Personal Trainer Manual (4th edition). Any noted postural deviations, scapular instabilities and ROM limitations in the thoracic spine or shoulder should be addressed through the client’s program.

Exercise Program

Exercise programs focused on improving scapular stabilization should include exercises to increase strength and endurance in the muscles that act on the scapula, increasing muscle length to correct inhibited ROM, and retraining the body to have better posture with good scapular positioning. Shoulder packing, which involves pulling the shoulder blades down and back into a retracted and depressed position and holding for five to 10 seconds per repetition, is a great exercise to use with clients, both during the dynamic warm-up and as part of their daily routines. Shoulder packing helps retrain the muscles to hold the scapula in a good position, improving kinesthetic awareness, posture, and strength and flexibility of the muscles that act on the scapula.

In addition to shoulder packing, incorporate into the dynamic warm-up shoulder stabilization movements that produce the letters I, Y, T, W and O. These exercises can begin in the supine position initially to improve ROM, progress to standing upright to increase resistance, and then progress to prone position with advancement to prone on a medicine ball. Prisoner rotation is another good exercise to include in the warm-up to increase thoracic mobility to allow for better shoulder mechanics during the primary workout.

Bradley and Tibone (1991) used electromyography (EMG) to collect data on the response of key shoulder muscles to various exercises. Any exercise that produced substantial effort, based on EMG response, in more than one muscle was identified as a “significant” exercise. They identified six primary movements that were labeled “significant” and should be included in any exercise program designed to improve shoulder stability and function. These exercises include:

- scapular plane elevation (scaption) with thumbs up

- scaption with thumbs down

- rowing

- push-up plus

- seated press-up

- horizontal abduction with external rotation

Scaption places the rotator cuff in the least stressful position for exercise, and is defined as elevation of the shoulder in the scapular plane, which is 30 degrees forward of the frontal plane (Houglum, 2005). Scaption with the thumbs down (“empty can”) has more recently been found to significantly increase the chance of shoulder impingement (American Council on Exercise, 2009). As a result, this exercise has been replaced by shoulder abduction in the scapular plane and is listed with the other “Key Shoulder Stabilization Exercises” in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Key Shoulder Stabilization Exercises

|

|

Exercise

|

Movement |

Muscles activated/ strengthened

|

|

1. Scaption with thumbs up

|

Arm raise in the plane of the scapula to below horizontal with elbows slightly bent and thumbs up

|

Scapular stabilizers – rhomboids, trapezius, levator scapulae, serratus anterior, pectoralis minor

|

|

2. Shoulder abduction in the scapular plane*

|

Arm raise in the plane of the scapula, starting with the thumbs down and rotating thumbs up as the humerus moves toward and then beyond horizontal

|

Subscapularis, anterior deltoid, posterior deltoid, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor

|

|

3. Rowing

|

Active scapular retraction and depression, with shoulder extension

|

Rhomboids, trapezius

|

|

4. Push-up plus

|

Active scapular protraction at the terminal end of a push-up motion (serratus “punches”)

|

Serratus anterior, pectoralis minor

|

|

5. Seated press-up

|

Pressing up to lift torso off seat

|

Rhomboids, pectoralis minor, pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi |

|

6. Horizontal abduction with external rotation

|

Reverse fly with shoulders externally rotated and thumbs pointing backward

|

Infraspinatus, teres minor, posterior deltoid

|

Based on Bradley and Tibone (1991); adapted from Houglum (2005)

* Adaptation from ACE Advanced Health & Fitness Specialist Manual (2009)

The exercises in Table 1 can initially be performed with minimal weight for clients who have significant shoulder instability or are new to resistance training, and can progress to more advanced exercises with heavier weight that incorporate the same motions. Once shoulder stabilization has begun to improve, isolated internal and external rotation exercises can be incorporated. The internal rotators include the strong pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, teres major and anterior deltoid, in addition to the subscapularis. Collectively, these muscles can produce far greater force than their antagonists that produce external rotation including the infraspinatus, teres minor and posterior deltoid. This becomes a factor when the external rotators are called upon to quickly contract eccentrically to slow down the explosive forces produced by the internal rotators seen in throwing and striking. This makes training the external rotators critical for shoulder joint stability and injury prevention, with particular attention paid to the eccentric phase of the exercise. To further enhance external rotation exercises, place a rolled-up towel between the client’s humerus and torso, with the elbow bent at 90 degrees, to increase the mechanical advantage of the external rotators (American Council on Exercise, 2009).

To improve range of motion in the shoulder complex, incorporate specific flexibility exercises in the cool-down that can address ROM limitations found during assessments and exercises. These can include stretches for the shoulder capsule, supine internal and external shoulder rotation, supine shoulder flexion and the 90 degree lat stretch.

Summary

The shoulder complex combines the more stable scapulothoracic joint with the more mobile shoulder joint to produce very large ranges of motion in all planes. Many factors can contribute to shoulder instability, and all of them increase the risk of shoulder injury. Clients at all levels of fitness will have shoulder instability. It is important to select the correct exercises and stretches to address their specific instability issues at appropriate resistance levels for their current fitness levels. For some clients, this will mean starting with isometric contractions and progressing to single-plane movements, then adding resistance and finally moving to diagonal and multiplanar movements. Exercises should not be painful, and any client who has recurring or extended pain should be referred to his or her physician for evaluation.

Clients will only work with you a few hours per week, so it is important to have them perform some of the key exercises focused on kinesthetic awareness, such as shoulder packing, to help them be mindful of their scapular position and posture throughout the day. This will improve shoulder position and posture over time, which will ultimately lead to better function of the shoulder complex and can improve total kinetic chain movement.

References

American Council on Exercise (2010). ACE Personal Trainer Manual (4th ed.). San Diego, Calif.: American Council on Exercise.

American Council on Exercise (2009). ACE Advanced Health & Fitness Specialist Manual. San Diego, Calif.: American Council on Exercise.

Bradley, J.P. and Tibone, J.E. (1991). Electromyographic analysis of muscle action about the shoulder. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 10, 789-805.

Floyd, R.T. (2009). Manual of Structural Kinesiology (17th ed.). New York, N.Y.: McGraw-Hill.

Houglum, P.A. (2005) Therapeutic Exercise for Musculoskeletal Injuries (2nd ed.). Champaign, Ill.: Human Kinetics.

_____________________________________________________________________

Todd Galati, M.A., is the director of credentialing for the American Council on Exercise. He holds a master’s degree in kinesiology, a bachelor’s degree in athletic training and ACE certifications as a Personal Trainer, Advanced Health & Fitness Specialist, Lifestyle & Weight Management Coach, and Group Fitness Instructor. Galati’s experience includes directing youth-fitness programs focused on reducing obesity, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes at the UC San Diego School of Medicine, teaching courses in biomechanics, applied kinesiology and human anatomy at Cal State San Marcos and San Diego State University, conducting human performance studies as a research physiologist with the U.S. Navy, personal training in medical, nonprofit and commercial facilities, and coaching endurance athletes.

Todd Galati, M.A., is the director of credentialing for the American Council on Exercise. He holds a master’s degree in kinesiology, a bachelor’s degree in athletic training and ACE certifications as a Personal Trainer, Advanced Health & Fitness Specialist, Lifestyle & Weight Management Coach, and Group Fitness Instructor. Galati’s experience includes directing youth-fitness programs focused on reducing obesity, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes at the UC San Diego School of Medicine, teaching courses in biomechanics, applied kinesiology and human anatomy at Cal State San Marcos and San Diego State University, conducting human performance studies as a research physiologist with the U.S. Navy, personal training in medical, nonprofit and commercial facilities, and coaching endurance athletes.