BY CARRIE MYERS

You work out to improve your cardiovascular fitness, muscular strength and endurance, and flexibility. You train your clients and students for the same reasons. But have you forgotten to breathe?

“By learning to control your breathing, by understanding how the respiratory system is integrated with your body, by using conscious breathing in all your pursuits, you will improve nearly every aspect of your life,” explains Al Lee, co-author of Perfect Breathing (Sterling Publishing, 2009). “Whether you’re a casual gym-goer, a mall walker, a mountain biker, an actor, singer or dancer, putting your breath at the core of your discipline will help you achieve far more than you ever thought.”

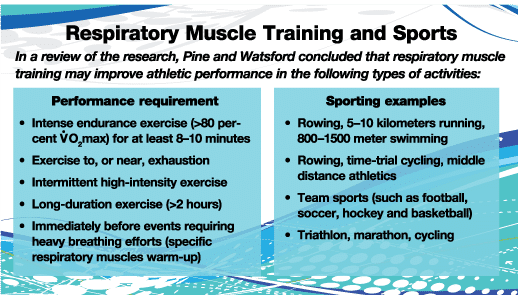

“During exercise, the body’s demand for oxygen increases and our breathing volume or ventilation must also rise,” explain Matthew Pine and Mark Watsford, both from the human performance laboratory at the University of Technology, Sydney. “This requires numerous muscles surrounding the lungs to contract in a highly coordinated manner. As the intensity of exercise increases, these respiratory muscles must contract more forcefully and more rapidly to keep pace with the body’s substantial increase in metabolism.”

However, in the same way that a stronger heart can push out more blood with each pump and as a result doesn’t have to beat as often, a stronger diaphragm and intercostals mean you can slow your breathing rate down and even get more oxygen to your muscles.

“By increasing the strength and stamina of your respiratory system, your breathing becomes more efficient, requiring less energy—which leaves more energy for the motor muscles and whatever task or activity you’re involved in,” explains Lee. “Therefore, you can take slower, deeper breaths, getting more oxygen out of each breath; you don’t have to work as hard to get it, because you don’t have to breathe as many times to get the same amount of oxygen.”

As an example, Lee cites studies that he and co-author, Don Campbell, came across with competitive athletes that showed an efficiency improvement of about 10 percent with respiratory resistance training. That means that at the same level of performance, they were consuming 10 percent less oxygen. “There was also an associated performance improvement of about 5 to 8 percent,” says Lee, “which would shave about three to five minutes off the time of a runner in a 60-minute race.”

That performance improvement, he explains, may also be due in part to improved focus. “When you are focused on your breath, you become intimately in touch with your mind, body and emotions and very much in the moment, which improves performance.”

In a study performed at the State University of New York at Buffalo, subjects who followed breathing resistance training improved their snorkel surface swimming time by 33 percent and their underwater Scuba swimming time by 66 percent.

“This is in agreement with previous studies in cyclists, rowers and runners,” explains study author, Dr. Claes Lundgren. “It suggests that athletes in most sports could improve their performance by undergoing respiratory muscle training. It is also clear that the greater the stress on the respiratory system, the larger the improvement in performance.”

During high-intensity exercise, when the respiratory muscles become fatigued, the body switches to survival mode and “steals” blood flow and oxygen away from locomotor muscles. As a result, these locomotor muscles become fatigued and performance can suffer significantly. Increasing the strength of the muscles involved with breathing, say study authors, through breathing-resistance exercise, can prevent this fatigue during sustained exercise situations, resulting in better performance.

Lee goes on to explain that if the diaphragm and intercostals aren’t exercised, they atrophy—just like any other muscle in the body. “For most adults, their breathing has slowly moved higher and higher into their chests over the years, so they’re taking little sips of air into the tops of their lungs and are barely using the diaphragm. In fact, if you’re not actively exercising it, the older you get, the more difficult it is to get it unstuck.”

Performance Breathing

Incorporating breathing methods into workouts is really nothing new. Yogis have been doing it for centuries, Pilates instructors for decades. And who hasn’t used breathing to aid in moving heavy weight—inhaling on the eccentric phase and exhaling on the concentric phase. Like yoga, though, the point of performance breathing—a term Lee and Campbell came up with to refer to using breath to enhance performance—is to help center and focus you, as much as it is to strengthen the respiratory muscles.

“Being in a relaxed state is important to achieving optimal performance in any endeavor, not just sports,” says Karlene Sugarman, M.A., author of Winning the Mental Way (Step Up Publishing, 1999). “It’s a vital stepping stone to peak performance [whether you’re working out, giving a presentation or dealing with your children]. The [individual] that is mentally and physically relaxed and has ‘quiet intensity’ is the one that is going to come out on top.”

One way to achieve this quiet intensity is through breath control.

“Try performance breathing during your next workout,” says Lee. “This simple technique can immediately improve your athletic performance, and is especially well-suited to repetitive-motion activities, such as running, cycling, swimming, etc.”

Lee explains that focused breathing helps to maximize your energy intake, while keeping the mind “in the body” and clear of distracting, self-limiting thoughts.

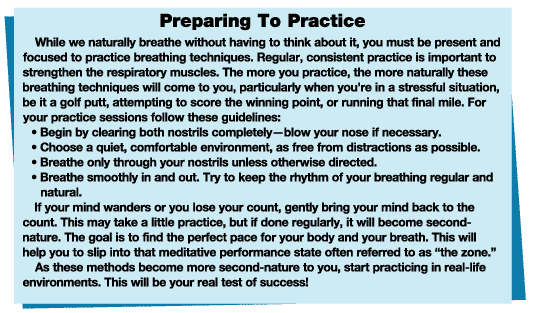

Before beginning, make sure you’ve followed the “Preparing to Practice” guidelines (see sidebar). Lee also stresses the importance of being able to comfortably complete deep, full breaths. When first beginning this method, it will probably feel uncomfortable and unnatural. That’s why practice is important.

The breathing cycle for this exercise is divided into three parts, each part getting a set number of counts:

- Inhale (2 counts)

- Hold the breath (2 counts)

- Exhale (4 counts)

Once you’re comfortable with this method, Lee then suggests applying it to your activity. As an example, for walking:

- Inhale for 2 steps

- Hold for 2 steps

- Exhale for 4 steps

If you’re a cyclist, replace steps with pedal strokes, swimming strokes for swimming and so on, depending on your activity.

Ultimately, you want to find a pace and count that you can maintain and that feels natural. As you become more adept with this technique, try and increase your counts while keeping the same ratio. For example, inhale for 4 counts, hold for 4 counts, exhale for 8 (or 6, 6 and 12). Experiment and find a combination that works well for you.

Not a breathing convert? At the very least, says Lee, simply become more conscious of your breath. A great way to practice breath consciousness—or your breathing cycles—is in bed. A fringe benefit: It’ll probably quickly send you off to dreamland.

“[Focusing on your breathing] brings you back to the present moment,” explains Campbell. “There’s no way you can think about yesterday or tomorrow when you’re concentrating on your next breath.”

_________________________________________________________________________

CARRIE MYERS has a B.S. in exercise science and has been a freelance writer for more than 11 years. She’s the author of the award-winning book, Squeezing Your Size 14 Self into a Size 6 World: A Real Woman’s Guide to Food, Fitness, and Self-Acceptance, and presents, teaches and trains in New Hampshire and Vermont.