Consider this scenario: A client hires a personal trainer for a 12-week training program leading up to their wedding, hoping to lose some weight for their big day. Halfway through the program, though the trainer has been preaching patience every step of the way, the client is upset because they’ve lost only 2 pounds, not the 12 pounds they had anticipated based on the trainer’s statement that 2 pounds per week is a safe and sustainable rate of weight loss.

The client is not responding to the exercise program in the way they’d hoped, but does that mean they are a non-responder to exercise? And, is the “lack of results” in this case the fault of the trainer, the client or the program itself? And, most importantly, how should the trainer respond to this pivotal moment in their relationship with this client?

What is a Non-responder?

In most pieces of exercise science research, there are individuals identified as non-responders, meaning that they did not experience the expected outcomes of that particular study. They can usually be found near the intersection of the x and y axes and their presence is often lost when the researchers summarize their findings, which typically deal more with averages than individuals.

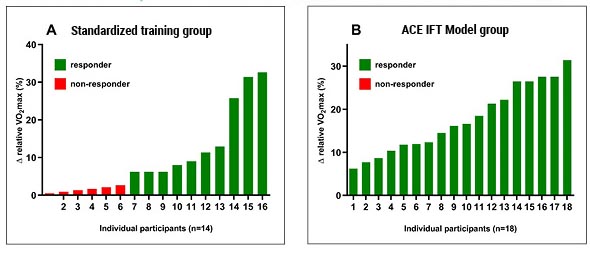

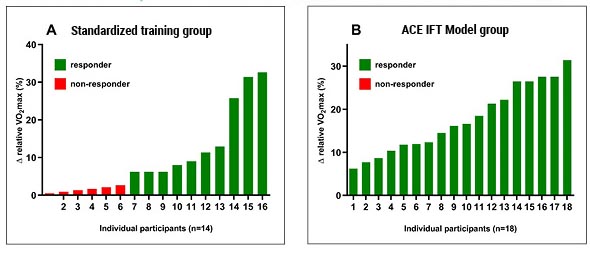

For example, in Figure 1 [which is from ACE-supported research investigating the effectiveness of the ACE Integrated Fitness Training® (ACE IFT® Model)], you can see that the standardized training group had six non-responders out of 16 individuals. In this case, the outcome being measured is maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), which is often used as way to quantify cardiorespiratory fitness. While there are six non-responders, the average outcome in this group shows an improvement in VO2max, so those individuals essentially vanish in the math.

|

Figure 1. Individual variability in relative VO2max response (% change) to exercise training in the standardized training (A) and ACE IFT Model (B) groups

|

What does all of this mean in the real world, where health coaches and exercise professionals like you are working with individuals—not averages—who are often seeking and paying for a particular outcome and expecting results? It’s not as though you can say, “Well, I guess you’re a non-responder!” and move on to your next client.

And, how often does this actually happen?

“All the time,” says Tasha Edwards, ACE Certified Group Fitness Instructor and founder of Hip Healthy Chick, who says that clients sometimes expect to see unreasonable results in a short timeframe. Chris Gagliardi, MS, Scientific Education Content Manager at ACE and an ACE Certified Personal Trainer, Health Coach, Group Fitness Instructor and Medical Exercise Specialist, agrees, saying, “A lot of times, what’s viewed as not responding is really not getting the desired outcome in the timeframe when you think it should be happening.”

Clearly, the existence of non-responders is not solely a research phenomenon. “As an exercise professional or health coach, being prepared to discuss the possibility of not responding to exercise as expected is really important,” Gagliardi says.

Setting Expectations and Goals

In the initial sessions with a new client, it’s essential that you set clear expectations and help the client develop reasonable goals. The classic example is weight loss, but other common goals include everything from enhanced fitness and strength to improvements in blood pressure or blood glucose. Regardless of the targeted outcome, setting reasonable expectations and timelines is vital to avoiding frustration down the road.

Clients can set lofty goals, Edwards explains, but what is required to reach them is often unsustainable, unsafe and unhealthy. She suggests coaches and trainers focus more on relationship building and rapport, emphasize feeling better physically and psychologically, and focus less on the numbers.

Unfortunately, as a trainer or coach, you may feel pressured to deliver results quickly and may connect your own value to your clients’ achievement of these outcomes. Training and coaching, Edwards says, sometimes require that we slow down and focus on form or talk about behavior change or shifts in a client’s lifestyle. It shouldn’t be about putting in maximal effort every day to push toward a singular goal.

In addition, having a single targeted outcome creates an all-or-nothing scenario where a client is set up to succeed or fail based on one number. This, of course, is not how goals and expectations should be established.

This is one reason why Lance Dalleck, PhD, professor of exercise and sport science at Western Colorado University, began using MetS z-score (which you can learn more about here) in place of VO2max in the ACE-supported research he conducts. MetS z-score broadens the ability to assess an exercise protocol by combining a number of values into a single score, including blood pressure, circumference measurements, blood glucose, high-density lipoprotein and triglycerides. As he explains, “You’re able to capture many more of the possible benefits of exercise.”

The lesson to be learned here and transferred from the laboratory to the real world is the importance of having multiple ways to gauge success. For example, if you are working with a client who has weight-loss goals, you might consider also taking various circumference measurements or determining body-fat percentage. For nearly all exercisers, Dr. Dalleck explains, there will be some variables that are improving even when others are not. For that reason, having a broad spectrum of things to evaluate can be helpful.

Edwards offers an important caveat regarding using such measurements: Be very mindful of what each client wants measured and be sure to adhere to those rules. Edwards works with a lot of women who are approaching or are in the midst of menopause and are struggling with the changes they see taking place in their bodies. For these clients, bringing out the scale or skinfold calipers can create a lot of stress and anxiety—not exactly the vibe you want to establish with your clients.

Instead, she emphasizes some of the less quantifiable benefits of exercise, such as feeling better, having more energy, sleeping more and feeling less stressed. Instead of recording the results of a weekly weigh-in, for example, you might ask how it feels when they play with their kids or whether they’re feeling more mobile or stronger when performing their activities of daily living.

Finally, she says to remind clients to be mindful of moments when the results of their hard work show up in unexpected ways. “They sometimes don’t know they’re getting stronger until something requires them to show their strength,” Edwards says.

Be Mindful of the Margin of Error

Dr. Dalleck brings up another consideration that is sometimes lost when research protocols move to the real world—the margin of error. The margin of error of a measurement can sometimes overlap with the expected outcome. For example, a person’s weight can shift by a few pounds or more based on hydration level, the time of day, what they’re wearing and countless other variables. So, if the expected weight loss is 1 to 2 pounds per week, that variability exceeds the targeted change.

Skinfold calipers are a great example of a tool that is commonplace in fitness facilities but that carries a considerable margin of error based on not only the quality of the tool but also the skill level of the practitioner. In fact, skinfold calipers are no longer featured in ACE’s personal training textbook for this very reason.

The margin of error of skinfold calipers is typically around 3 to 5%, which overlaps with the percent change that people often target through training. In other words, if a person wants to lower their body-fat percentage by 5% and the margin of error of the measurement tool can reach 5%, then those numbers are essentially meaningless.

Most people probably falsely assume that every number they get is precise, explains Dr. Dalleck, and that’s often not the case.

Taking an Experimental Approach

One thing to understand about the use of the term “non-responders” in the scientific literature is that studies are measuring specific outcomes following a specific type, intensity and duration of exercise programming. And, there is a predetermined end date, which is not the case when working with clients who are making long-term lifestyle changes. Taking an experimental approach in the real world involves learning from each experience and trying something new.

Consider a client who takes two group fitness classes and completes one strength-training session with you each week. They do this for 12 weeks but do not achieve the weight loss they expected. If this were a study, the intervention would be over and they would be labeled a non-responder. In the real world, there are a few things you can do at this point.

If this were your client, your first step would be to talk to them about other benefits they may be seeing. Are they less stressed? Are they able to play more with their grandchildren? Are they enjoying socializing in the gym? Are they sleeping better?

Next, think about how you might adjust the program itself (more on this below). Can your client add a third class or second strength-training session? Can the intensity of any of those workouts be increased? Should they try to add a new type of exercise?

Finally, talk to the client about other elements of their lifestyle outside of exercise. Do they need nutritional support? Do they have social support at home? Are there any new considerations or stressors that weren’t present at the outset of your time together?

The point is, you can work with the client to learn from the experience and make adjustments that will help them reach their goals, while simultaneously evaluating the goals themselves. Perhaps they’ll find that reductions in stress and a growing social circle are just as important to them as weight loss.

You can also explain to clients that not everyone reacts to every type of exercise in the same way or at the same pace. Most people know this intuitively when it comes to nutrition, as we all know people who lose weight very easily through relatively minor changes in their diet and others who struggle with weight maintenance their entire lives despite trying just about everything.

However, we don’t think often about exercise in this way. Gagliardi describes this as having a high or low sensitivity to exercise. Everyone has a different response to food, stress, inadequate sleep and even medications—so why would we expect everyone to respond to exercise in the same way?

“It’s really important to focus on how the client is responding so you can make adjustments along the way once you realize something’s not working,” says Gagliardi.

As a trainer or coach, you’re not prescribing a set protocol and sticking with it, as is often done in the research. Instead, you should be learning and adjusting every step of the way.

Talking to Clients and Avoiding Labels

Unfortunately, there will be times when clients become frustrated at a perceived lack of results. In addition to taking an experimental approach in which there are no failures, just lessons learned, it’s important to remind clients to focus on the future. Even if they’re upset by the pace of progress, they’ve established some good habits and there are plenty of other forms of physical activity they can try.

This can be a good time to revisit the underlying values that support the goals they’ve set. Why do they want to lose weight? Why do they want to get stronger? Why is taking control of their health by improving blood pressure or blood glucose numbers so important? Reengaging with their “why” can help clients see that success can come in many forms that are not so easily measured.

“The first thing to do is really listen to what they’re saying without trying to discredit any of it,” says Edwards. Then, “Follow the client’s lead. Period.”

Gagliardi agrees. “When the person is in that moment of frustration,” he says, “acknowledge their feelings and try to move the discussion forward into the future.”

It’s also vital that you avoid labeling anyone as a non-responder, particularly as this term is becoming more well-known and has started showing up in articles and blogs written for the general public. The term “non-responder” should be reserved for research papers and never be used to describe anyone in a fitness setting or context.

Gagliardi warns against falling into a labeling trap, which occurs when you name a problem that needs to be fixed. If a client accepts the label of non-responder, they may think that exercise is never going to work for them and that it’s simply not worth the effort.

“I think it’s important to acknowledge if a certain type of program didn’t work and isn’t delivering the results that we would expect,” says Dr. Dalleck. However, avoid labeling the individual and instead say, “Let’s do another iteration of this program and change some things.”

Both Gagliardi and Dr. Dalleck point to the ACE Mover Method™ as a model of how to talk to clients at moments of frustration in order to prevent potential dropout. Five to 10 minutes of purposeful conversation during an exercise session can help you work with the client to break down barriers and collaborate on next steps.

Adjusting the Program

When it comes to adjusting the exercise program, the possibilities are endless. You may begin by making modifications based on one or more of the elements of the FITT principle—frequency, intensity, time and type—or by switching from weight-stack machines to free weights. You may take treadmill exercise outdoors or change from lifting weights alone to joining a group exercise class or taking part in a small-group circuit training format.

However, the best way to ensure that your clients respond to your programming is by personalizing it. As Gagliardi says, “The more personalized the program is, the less chance there is of not responding.”

This is where the ACE IFT Model comes into play. ACE-supported research has repeatedly demonstrated the effectiveness of this personalized exercise programming tool in comparison to more traditional training models (refer to the introduction of the research linked above). This type of personalization, coupled with proper goal setting and use of the ACE Mover Method, is the best recipe for long-term success in an exercise program.

Of course, there is no guarantee of success, regardless of how well thought out your programming may be, as there are countless variables at play. Let the client lead the way as you periodically revisit their goals and values and remain vigilant in monitoring their responses to exercise and then modifying the program accordingly.

A good health coach or personal trainer, Edwards explains, will pick up on what clients are telling them about their lives and be able to shift the approach—at each and every session, if necessary.

Taking a More Holistic Approach

Taking a more holistic approach to both goal setting and programming will help guard against clients feeling like they’re not responding to exercise. Consider all lifestyle factors when setting and monitoring goals. In addition, help clients see the connections among sleep, stress, nutrition and exercise. If they’re in a high-stress period, for example, they may not sleep as well, may be eating less healthfully and may not be able to perform as many repetitions during a set as they normally would.

Improving just one of those elements will positively impact their performance and overall well-being and start a chain reaction among the other elements. Educating clients on how these puzzle pieces fit together may help them avoid all-or-nothing thinking, where falling short of a single goal feels like a failure.

In Conclusion

The primary cause of people feeling like they’re not responding to a training program is a failure to set reasonable goals and expectations at the outset. During those early conversations, talk about the full spectrum of potential responses to training and the many variables that may impact their ability to hit their goals. This may help clients realize the importance of having an overall healthy lifestyle, as opposed to thinking one or two coaching or training sessions per week are enough to make them lose weight, get more fit or achieve whatever goals they have established.

Finally, Edwards reminds us to “look at clients as whole people with whole lives.” They’re resourceful on their own, she says, and not lacking anything that you’re going to give them. Sometimes, your role as a professional is to present things from a different perspective and then let them take the lead.

“Be invested in their whole, holistic self,” Edwards says, “and avoid thinking that it’s just about exercise—because normally, exercise is the easy part.”

by

by