It seems like every time I go to the gym, I see people doing rotator cuff exercises incorrectly. Given the importance of this quartet of stabilizers and decelerators, it is essential that they receive adequate and appropriate training to ensure effective and efficient movement. This is true of your everyday clients as well as your athletes.

Form Follows Function

Understanding movement requires understanding the function of the musculature before determining the form of exercise that is required.

Although the rotator cuff muscles are involved in internal and external rotation of the humerus, the primary and essential function they serve is to decelerate the humerus during powerful movements and to stabilize the humerus in the glenoid fossa during all movement. Unlike internal and external rotation, these are not concentric and eccentric contractions, but instead a series of short burst isometric contractions. Though potentially valuable in phase 1 post-injury rehabilitation for muscle reeducation, concentric and eccentric movement is not helpful in improving the function of the rotator cuff.

In deceleration and stabilization, the muscle group turns on and then off in a series of isometric contractions that last milliseconds. You cannot consciously train muscles to turn on and off at that rate, but you can set up the appropriate environment for that sequence to occur, with the requisite overload, in a safe, effective setting.

5 Essential Exercises

1. Warding Patterns

Warding patterns are great for any client. Because they feature manual resistance, you can add more or less resistance based on the client’s capabilities in the moment. Warding patterns train the on-off neurological behavior of the muscle. This movement pattern should be done within a pain-free range of motion if your client is returning from injury. It should be done in a functional range of motion for an asymptomatic client. The functional range of motion of a tennis player requires a significant amount of stability throughout the shoulder range of motion, while your 80-year-old client may simply require enough stability to put her can of soup in the cabinet overhead. Choose the movement pattern based on the daily activities of your client.

2. Quadruped Alternating Arm and Leg Lift

Though most popular for posture and core training, this exercise is an excellent way to introduce proper scapular positioning during movement. The closed-chain, quadruped position gives your client a strong support link to the floor, allowing him or her to better adjust positioning and strengthen the scapular stabilizers in position while working on the stability sequence of the rotator cuff.

3. Stability Ball Push-ups

Performing push-ups on an unstable surface, such as a BOSU, Indo Board or stability ball, requires the rotator cuff to stabilize the glenohumeral joint. It is another great exercise to train the scapular stabilizers in concert with the rotator cuff. When cueing, ensure that the spine stays long to avoid head drop or hyperkyphosis of the thoracic spine. Regress this exercise to knees on the floor or wall push-ups on the ball if your client is unable to maintain control of the scapulae.

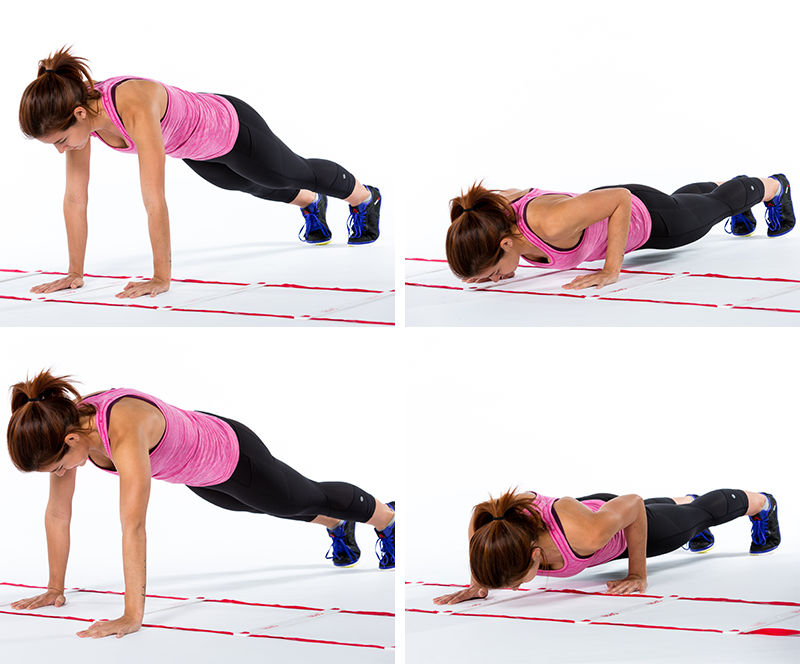

4. UE Ladder Drill

This exercise requires more coordination and power than the stability ball push-up. Although it includes a greater range of motion, it does not train the arm in the extreme overhead position, which is necessary when training the overhead athlete. As you would with footwork, change up the movements of the hands as your client moves down the ladder. This requires stability throughout a larger range of motion. Because the hands are in non-symmetrical positions, there is a higher demand on the rest of the kinetic chain as well. The most advanced athletes can add a plyometric component with a plyo-push-up down the ladder.

5. Whole-body PNF Patterns

The rotator cuff works in concert with the kinetic chain. During an overhead activity intended to accelerate an object forward (e.g., a baseball pitch or volleyball serve), the entire posterior chain works in concert to slow the forward momentum of the body and, in turn, the humerus. With this in mind, it makes sense to involve the entire body in the motion. The whole-body PNF pattern can be performed in a squat position, lunge position or even on one leg. Both acceleration and deceleration are inherent in this movement pattern, giving your high level and asymptomatic client a well-simulated overload environment in which to train the rotator cuff.

If your client is returning to sport or activity following an injury, your role as a personal trainer is to see to his or her strength and progression post-rehabilitation. Work closely with your client’s certified athletic trainer or physical therapist to ensure that you are aware of the phase of rehab the client has reached. And remember, if your client begins to speak of pain during the exercises, you must refer to a doctor.

For the asymptomatic athlete or client, these exercises are a great way to keep the rotator cuff healthy and strong, preventing future injury. I wouldn’t train any client without them.

by

by

by

by