By TODD GALATI, M.A.

Overuse injuries commonly result from training errors such as repetitive motions and training loads that are increased too quickly. When the activity of choice includes repetitive sagittal plane (anterior-posterior) movements of the knee and hip, iliotibial band syndrome can be a surprising and painful consequence.

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS), also referred to as iliotibial band friction syndrome (ITBFS), is an overuse injury that occurs when the distal portion of the IT band rubs repeatedly over the lateral condyle of the femur at approximately 30 degrees of knee flexion. This causes inflammation and pain that can be described as “sharp” and “burning.” A quick analogy could be to think of a climbing rope rubbing repeatedly over a protruding rock; eventually microtears appear that can lead to something much worse. In the case of ITBS, the “rope” being damaged is human connective tissue.

IT band issues can be seen in both active and sedentary individuals; however, it is most commonly seen in runners, cyclists, volleyball players and weight lifters (Anderson, Hall and Martin, 2008). Individuals who have a leg-length discrepancy, large Q-angle, genu valgum (knocked-knee appearance), or pronounced foot pronation may have a predisposition to ITBS (Houglum, 2005). Training factors that can result in ITBS including overtraining (e.g., increased intensity, distance, frequency), increased hill running (especially downhill), improper footwear or equipment use, changes in running surface, and muscle imbalances (e.g., weakness or tightness) (Houglum, 2005; Martinez and Honsik, 2006).

As with other injuries, it is important for individuals who have acute or chronic ITBS to seek medical attention. Fitness professionals can work with clients who have experienced ITBS once they are pain free and have been cleared for Iliotibial band exercises following any medical treatment or physical therapy. It is important to obtain the client’s consent to correspond with his or her physician or physical therapist to determine the appropriate starting point for the exercise program.

Iliotibial Band—Structure and Function

Many of the factors that lead to ITBS are related to an individual’s anatomical structure and training variables. Therefore, it is important to understand the structure and function of the IT band to be able to develop and progress exercise programs that address the structural and training factors that lead to ITBS without aggravating the tissue.

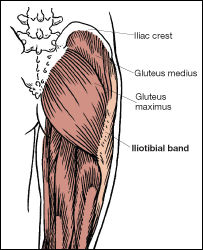

Structurally, the iliotibial band is an extension of the lower tendon fibers of the tensor fasciae latae (TFL) and the gluteus maximus. This wide band of fibrous connective tissue extends from the TFL and gluteus maximus down the lateral side of the thigh and across the lateral knee to its insertion point just anterior to the lateral tibia on Gerdy’s tubercle. Note that the lower fibers of the IT band also attach to the patella and the biceps femoris via fascial connections (Brotzman and Wilk, 2003).

Functionally, the IT band is under tension when either the TFL or gluteus maximus contract, resulting in regular tension on the IT band during squatting and jumping, and throughout repetitive motions such as running and cycling. The IT band also serves as both a shock absorber and a lateral stabilizer for the knee and hip, especially throughout the stance phase during gait. This is pronounced during running, as the TFL and gluteus maximus act together to pull on the IT band during the initial stance phase when the knee is flexed, and also as the gluteus maximus fires as part of the posterior oblique myofascial sling from terminal stance through toe-off.

Failing to stretch correctly has been noted as a key risk factor for ITBS (Anderson, Hall and Martin, 2008; Martinez and Honsik, 2006). If the IT band is shortened, it will pass more tightly across the lateral knee, eventually causing it to rub with greater pressure over the condyle, causing microtears that can eventually lead to inflammation and ITBS. Flexibility exercises are therefore an obvious focus for any exercise program for clients who have recovered from, or are at risk for, ITBS. This includes specific stretches for the IT band and the use of a foam roller for self-myofascial release; however, it is important for the personal trainer to remember that the body does not move in isolation and a tight IT band can affect the entire kinetic chain.

The IT band connects to the pelvis via the TFL (ilium) and the gluteus maxiums (ilium and sacrum), crosses the hip and knee joints, inserts on the tibia, and has fascial connections to the patella and biceps femoris. A tight IT band can therefore limit movements of the pelvis, hip, knee and knee cap. Limiting mobility in these joints can cause hypermobility in adjacent joints, including the lower back and ankle and foot. IT band tightness can also pull laterally on the patella and tibia, causing potential mechanical issues at the knee, and pull on the distal end of the biceps femoris. This could also potentially impact the posterior, or deep, longitudinal myofascial sling.

In some individuals, IT band tightness will cause increased pressure on the trochanteric bursa, which sits between the greater trochanter of the femur and the IT band. If this condition persists, it can lead to inflammation of this bursa known as trochanteric bursitis. Trochanteric bursitis will often result in tightness, pain and tingling or numbness over the greater trochanter that can radiate down the IT band. Trochanteric bursitis can result from either direct impact to the bursa, or some of the same structural and training factors that cause the IT band to become shortened, leading to ITBS.

Exercise Programming

The first step in designing the exercise program is to make sure that the client is not currently experiencing ITBS symptoms. Conduct a thorough health-history interview to help the client identify factors that trigger the tightening of the IT band that leads to ITBS. This can include specific types of activities, certain exercises, increases in training load or lack of recovery time. Perform a basic postural screening to look for pronounced foot pronation (flat feet), genu valgum (knocked-knee appearance), or larger Q-angles (a wider pelvis coupled with knees that are close together results in a larger Q-angle). These structural issues will provide information that should be considered during exercise programming.

Have the client walk normally across an open space or on a treadmill. Look for any noticeable deviations in gait that could be due to tight IT bands or muscle weakness. You should assess flexibility at the hip (e.g., Thomas test, passive straight-leg raise) and have the client perform an IT band stretch (Figure 1) to establish a baseline indication of range-of-motion (ROM) limitations due to IT band tightness. You can also assess unilateral lower-limb stability by having the client perform the hurdle step screen.

Figure 1. IT Band stretch

Source: American Council on Exercise (2010). ACE Personal Trainer Manual (4th ed.). San Diego: American Council on Exercise.

The initial exercise program should focus on improving range of motion (ROM), especially in the hips, knees and lower back, and restoring neuromuscular control of the core, hips and knees. Start with open-chain exercises to restore initial strength, such as side-lying hip abduction, hip adduction and “clams,” and then progress to closed-chain exercises. Some clients may initially have difficulty with exercises such as lunges and squats. Begin with quarter lunges and quarter squats (to 45 degrees of flexion) and then gradually progress to 90 degrees and beyond as tolerated. Initial exercises should be performed in the sagittal plane, then frontal plane and, finally, combined planes of motion. As fitness improves, the exercises should progress (easy to hard) in the sagittal, frontal and combined planes as presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1. Suggested Close Kinetic Chain Progression for the Lower Extremity

|

| Plane of Motion |

Exercise Progression (Easy → Hard) |

| Sagittal plane |

Leg press machine → wall squats with ball → forward lunges → stair stepping → bilateral squats on a foam pad → bilateral squats on air-filled discs or a BOSU® → single-leg squats on the ground → single-leg squats on a foam pad → single-leg squats on an air filled disc or BOSU |

| Frontal plane |

Side stepping on a level surface → side stepping up onto a step → side stepping with bands → side stepping (fast) with ball passing → slide board |

| Combined planes |

Multidirectional lunges → single-leg balance with multidirectional toe touch → single-leg reach → multidirectional hops (bilateral) → multidirectional hops (single leg) |

Source: American Council on Exercise (2009). ACE Advanced Health & Fitness Specialist (4th ed.). San Diego: American Council on Exercise.

During this time of progression within the different or combined planes of motion, basic balance activities can be integrated into the client’s program while he or she performs closed-chain movements. This will increase the balance challenge and facilitate proprioceptive adaptations to exercise. Table 2 provides options for progressing the balance challenge from bilateral balance to basic single-limb basic exercises, and then to advanced single-limb exercises.

|

Table 2. Suggested Balance Progressions

|

| Difficulty Level |

Exercise Progression (Easy → Hard) |

| Level I (bilateral balance) |

Ground → mini-trampoline → foam pad → air-filled discs → BOSU® → wobble board |

| Level II (single limb—basic) |

Ground → mini-trampoline → foam pad → air-filled discs → BOSU → wobble board |

| Level III (single limb—advanced) |

Level II progression with ball tossing → head turning (up/down or side/side) → head diagonals → eyes closed

Manipulate time and speed of movement

|

Source: American Council on Exercise (2009). ACE Advanced Health & Fitness Specialist (4th ed.). San Diego: American Council on Exercise.

It is important to teach the client a warm-up that will prepare the kinetic chain for movement in all planes of motion. The “Warm-up and Cool-down for Runners” workout includes an effective warm-up that can prepare the kinetic chain for running and other endurance events. Cardiorespiratory exercise also plays an important role in the client’s program, with a primary focus on improved health and fitness. Be sure to have the client return to cardiorespiratory exercise in a slow, progressive manner to facilitate program success and adherence.

The flexibility program should focus on improving ROM across the kinetic chain, with increased emphasis on the IT band and the muscles acting on the hip, knee and lower back. The sequence of stretches performed can enhance or inhibit the effectiveness of the flexibility program, specifically at the IT band. For example, tight hamstrings could limit ROM during the IT band stretch, placing the emphasis of the stretch more on the hamstrings than on the IT band. Therefore, it is important to first stretch the muscles of the hips, knees and low back to prevent any inhibition of IT band lengthening during more focused IT band–specific stretches and self-myofacial release. The cool-down in the “Warm-up and Cool-down for Runners” workout provides a flexibility sequence that is focused initially on stretching the muscles of the torso, gluteals, hamstrings and hip flexors, prior to introducing IT band specific stretches.

Summary

Iliotibial band syndrome usually flares up due to structural and functional factors that combine to progressively shorten the iliotibial band, causing it to eventually rub on the lateral condyle of the femur. Even after a client’s symptoms of ITBS subside, he or she is at risk for additional flare-ups until the IT band is lengthened and the ROM and strength of the core, hips and knees are improved. By implementing an exercise program based on commonsense principles, fitness professionals can help their clients improve movement, strength and balance, while also limiting their chances for having future bouts with ITBS.

References

American Council on Exercise (2009). ACE Advanced Health & Fitness Specialist Manual. San Diego, Calif.: American Council on Exercise.

American Council on Exercise (2010). ACE Personal Trainer Manual (4th ed.). San Diego, Calif.: American Council on Exercise.

Anderson, M.K., Hall, S.J. and Parr, G.P. (2008). Foundations of Athletic Training: Prevention, Assessment, and Management (4th ed.). Baltimore, Md.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Brotzman, B. and Wilk, K. (2003). Clinical Orthopedic Rehabilitation (2nd ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby.

Floyd, R.T. (2009). Manual of Structural Kinesiology (17th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Houglum, P.A. (2005) Therapeutic Exercise for Musculoskeletal Injuries (2nd ed.). Champaign, Ill.: Human Kinetics.

Martinez, J.M. and Honsik, K. (2006). Iliotibial band syndrome. E-Medicine Online Journal (Web MD). Dec 6, 1–14. www.emedicine.com.

Todd Galati, M.A., is the director of Academy for the American Council on Exercise. He holds a master’s degree in kinesiology, a bachelor’s degree in athletic training, and four ACE certifications (Personal Trainer, Advanced Health & Fitness Specialist, Lifestyle & Weight Management Consultant, and Group Fitness Instructor). Galati’s experience includes directing youth fitness programs and research at the UC San Diego School of Medicine, teaching courses in biomechanics, applied kinesiology, anatomy, and physiology at Cal State San Marcos and San Diego State Universities, conducting human performance studies as a research physiologist with the U.S. Navy, personal training in medical fitness, non-profit and commercial facilities, and coaching endurance athletes to state and national championships.