By MEGAN SENGER

Have you ever wondered why some exercises are considered contraindicated by the fitness community, yet are standard fare in yoga? Consider moves like the yoga plow, deep knee bends, or unsupported forward hip flexion. These have long been considered controversial in the gym, yet are commonplace in the yoga studio.

But if an exercise is considered “contraindicated” or “high-risk” in the gym, can it still be beneficial in a mind-body setting? Three experts weigh in on what fitness professionals need to know.

Asana Analysis

The experts—all of whom hold advanced degrees, are trainers of yoga instructors and teach yoga classes themselves—analyzed five common asanas (yoga poses) as performed by healthy, experienced participants.

Of special note: yoga poses are static (non-moving) and sustained (typically for three to five cycles of breath). Body weight alone is used as resistance. This means that each yogic perspective is not directly applicable to a similar-looking weighted rep in the gym, and one should use caution when comparing the two.

1. Yoga Plow (sanskrit name: halasana)

The fitness controversy: Detractors of the yoga plow cite excessive cervical strain as the main reason to let this one go.

The yogic perspective: Contrary to common assumption, if the plow is performed correctly the thoracic and cervical vertebrae do not touch the floor, says Steven Weiss, M.S., D.C., a Sarasota, Florida-based chiropractor who lectures on the biomechanics of yoga to physical therapists, chiropractors and other health and fitness professionals through AlignByDesignYoga.com.

Weiss cues students to think of the movement as a “chest opener” to facilitate correct alignment. “The pose should rest as far onto the mid-deltoid muscle as possible and not even on the shoulder blades. The neck should not flatten, but [instead] maintain its normal lordotic curve.”

Unique benefits: Gravity is the key, according to Kathleen Sand, who holds a Ph.D. in biomechanics and lectures in the University of Southern California’s department of kinesiology in Los Angeles. A three-time sport biomechanist for the U.S. Olympic Committee, Sand notes that when reaching for one’s toes in a seated, legs-extended position, there is limited lengthening of the lumbar paraspinal muscles. However, in a yoga plow, gravity facilitates the lengthening of mid-to-low back paraspinals—a muscle group that may not be well addressed in upright, forward-fold stretch variations.

To modify the pose, stack several folded blankets under your client’s shoulders, or have them rest their toes on the seat of a chair, says Eden Goldman, D.C., a Los Angeles-based chiropractor. As co-director of Loyola Marymount University’s prestigious Yoga Teacher Training Program—one of the only such programs in the country that is associated with an accredited four-year university—Goldman cautions fitness professionals to always respect the needs of each individual and reconsider poses as required.

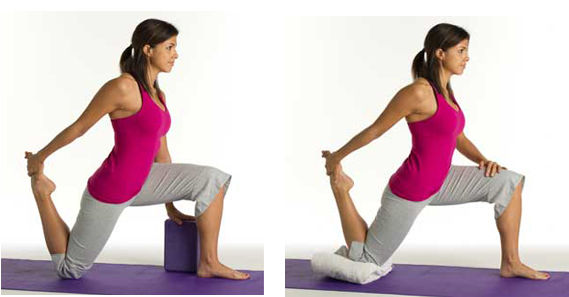

2. King Pigeon Variation II (eka pada rajakapotasana II; some practitioners may refer to this pose as low lunge II or anjaneyasana II)

The fitness controversy: A variant of a kneeling quadriceps stretch, this asana is noted for imposing isolated point pressure on the rear patella.

The yogic perspective: “Where you orient your weight, and the central axis of the pose, will determine where stress loads are experienced by the practitioner,” explains Goldman.

Sand notes that two factors affect the load on the rear knee: the degree of bilateral weight distribution (potentially limited by tight ipsilateral hip flexors), and the degree of knee flexion imposed by the arm actively flexing the rear lower leg.

All three experts agree that a practitioner should shift the pelvis forward, taking weight off of the rear patella and shifting weight onto the distal end of the rear thigh. Weiss further states that unless students have enough hip-flexor flexibility to do so, he advises against this pose entirely.

Unique benefits: “This is one of the best ways to isolate the hip flexors on a yoga mat,” says Goldman. “Fixing the [rear] knee on the floor creates a closed-chain isolated stretch in the [rear leg’s] iliopsoas and rectus femoris.” He adds that since the rectus is a two-joint muscle, bending the back knee boosts the stretch’s intensity through the muscle’s middle and lower sections.

To modify, Goldman suggests placing a folded towel under the back knee, or a yoga block under the front hand for support.

3. Reclining Hero’s Pose (supta virasana)

The fitness controversy: The position of the knee in this pose recalls the rear hurdler’s stretch, which has long been removed from most fitness instructors’ repertoires.

The yogic perspective: Knee strain can be avoided with an active inward rotation of the anterior hip joints and thighs when entering this posture, the experts agree.

The feet should remain outside of the hips in passive plantarflexion (tops of the feet on the floor) according to Sand. Weiss notes that the patella and its tendon should remain neutral over the knee.

Unique benefits: “This posture offers a gravitational assist to stretch muscles on the front line of the body,” explains Sand.

For those needing modifications, Goldman suggests using props, such as a bolster aligned directly under the spine.

4. Garland pose (malasana)

The fitness controversy: The hyper-flexed hips and knees of a deep squat comprise a position that trainers typically avoid.

The yogic perspective: Weiss argues that this deep, unweighted squat is actually therapeutic for the knees, since it “opens” the joint and therefore removes direct pressure from the knee-end of the thigh-bone. “The ‘western’ squat drives the femur downward and compresses the femoral condyles into the tibial cartilage. In a yogic squat [like garland pose], the femurs drop away from the joint and create more space.”

Unique benefits: Sand notes that garland pose challenges balance and deeply lengthens uni-articular hip extensor muscles (such as the gluteus maximus and medius) and hip abductors.

For those needing a modification, Goldman advises a half-squat. Participants should sit back into their heels, with knees behind the toes and mid-foot. “This will decrease the shearing effect of the tibia on the anterior cruciate ligament.”

5. Halfway Lift (ardha uttanasana); with or without overhead arm extension

The fitness controversy: Unsupported forward flexion puts strain on the low back, which can be exacerbated by a full overhead extension of the arms.

The yogic perspective: “A halfway lift does not strain the lower back when performed correctly,” says Weiss. “The torso is in isometric contraction, strengthening the core’s musculature while maintaining the proper curvatures of the spine.”

Unique benefits: This halfway lift teaches a client how to rotate the body (head-arms-trunk segment) about the hip joint with the hip extensor muscles, says Sand. Thus clients learn to lift their upper body weight using the hamstrings and gluteus maximus (the agonists of overly tight hip flexors) instead of relying on trunk extensors such as the erector spinae and quadratus lumborum—and avoid potential back pain.

To modify, use the back of a chair as an arm support, or microbend the knees. “[Slightly bending the knees] equalizes the pressure loads by taking the slack out of the hamstrings and the compensatory strain off the spinal erectors,” says Goldman. Sand adds that bent knees will facilitate the anterior pelvic tilt necessary for hip flexion.

Curative or Contraindicated?

So are some yoga poses just inherently contraindicated?

Not if they are performed correctly, according to Goldman. “[Teaching yoga] requires education, intuition, practice and a deeper understanding of the big picture. Not employing these faculties when working with clients is the real contraindication.”

Weiss agrees. “Yoga can be revitalizing, restoring and healing, but can just as easily be dangerous and cause injury. It is the attention to alignment that determines which is the outcome.”

The experts’ top safety recommendations?

- Proper biomechanics and mind-body connection are more important than “getting into a pose.” Yoga is a way of learning proprioceptive and alignment awareness, rather than simply improving flexibility, says Weiss.

- The poses discussed in this article are for experienced, warmed-up practitioners. Pre-stretching target muscles is essential for advanced postures, cautions Goldman. Postures should align with an individual’s goals and health history, and some asana are simply inappropriate for beginners and those with specific limitations.

Same Person, Same Pose: What’s the Difference?

Sand notes that biomechanical considerations can change when someone performs the same yoga posture twice, but with different muscle activation cues each time. For example, imagine standing with your feet shoulder-width apart. Without visibly moving, you could “push out” with your feet by consciously activating your hip abductors, but with no visible change in your feet or body position. Conversely, if you “pulled inward” with your feet using your hip adductors, you would outwardly appear to be in the same pose yet generate very different forces in your muscles and joints. Sand cautions fitness professionals to be aware of these changing force nuances when considering the biomechanical analysis of a yoga pose—or any fitness movement.

Using Yoga Wisely

Well-designed yoga classes sequentially and cautiously take participants into increasingly challenging postures. In other words, yoga is safe when performed correctly. Practicing yoga without physical preparation, or at an inappropriate level of difficulty for the individual, can present a high risk of injury.

“There is nothing inherently ‘magical,’ or therapeutic, in the execution of any specific asana,” explains Weiss. “Yoga is essentially a sophisticated ‘alignment delivery system’ that, when practiced with precision, will create physiological changes that are positive.” As an ACE-certified fitness professional, you are in a unique position to support the safety, biomechanics and body-awareness of your clients’ yoga-based efforts, in the gym and beyond.

______________________________________________________________

Megan Senger is a writer, speaker and fitness sales consultant based in Southern California. Active in the exercise industry since 1995, she holds a bachelor’s degree in kinesiology and English. When not writing on health and lifestyle trends, techniques, and business opportunities for leading trade magazines, she can be found in ardha uttanasana becoming reacquainted with her toes. She can be reached at www.megansenger.com.

Megan Senger is a writer, speaker and fitness sales consultant based in Southern California. Active in the exercise industry since 1995, she holds a bachelor’s degree in kinesiology and English. When not writing on health and lifestyle trends, techniques, and business opportunities for leading trade magazines, she can be found in ardha uttanasana becoming reacquainted with her toes. She can be reached at www.megansenger.com.