By JIM GERARD

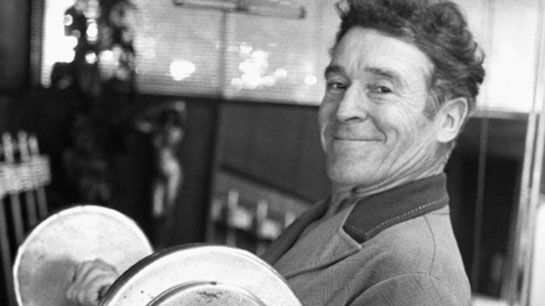

Maybe it was the skintight jumpsuit. Or the way he used ordinary household items in a starkly minimalist set to demonstrate calisthenics on his TV show. Or the juicer he touted. Or the stunts he did, like swimming the length of the Golden Gate Bridge while hauling boatloads of tonnage.

It may have been for any number of reasons, but for a long time fitness pioneer Jack LaLanne, who died earlier this year at the age of 96, wasn’t taken entirely seriously—even by the people in the industry he helped spawn. Judi Sheppard Missett, the founder of Jazzercise and a friend of LaLanne’s, says, “I think he was way ahead of his time, and didn’t get the credit he deserved, because people thought he was a little quirky. It took a long time before the country took him seriously. Yet, today, no one would dispute the things he preached: exercising and eating properly.”

“My workout is my obligation to life,” LaLanne once said. “It’s part of the way I tell the truth—and telling the truth is what’s kept me going all these years.”

Decades before Dr. Kenneth Cooper jump-started the aerobics revolution and Jane Fonda and Richard Simmons commodified it, before Nike turned running shoes into status symbols and Joe Weider built his bodybuilding empire, LaLanne was the fitness evangelist, a pioneer in the fight against an obesity epidemic he was one of the few to foresee.

Ash Hayes, former director of the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports under Ronald Reagan and Emeritus Historian of the ACE Board of Directors, says, “When I first started, [Jack] was a major catalyst in getting people interested in physical fitness. His show [The Jack LaLanne Show, which started locally in California in the early 1950s, and went national from 1959 to 1985] drew a lot of attention to it at a time when it was not in the public consciousness.”

A Role Model for All Ages

Dr. Steven P. Hooker, director of the Prevention Research Center at University of South Carolina, speaks to LaLanne’s historical importance[1]: “He was the first public figure to make exercising look fun.”

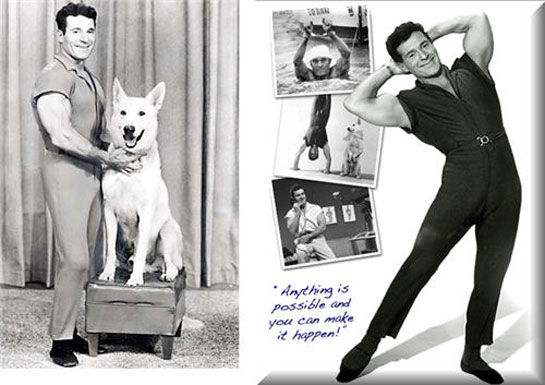

Hooker adds that LaLanne was a living demonstration of the idea that fitness was a democratic pursuit. “He was a great role model for people of all ages and for both genders.” He included his wife, Elaine LaLanne, on the show to demonstrate the exercises and as living proof that doing them would not ruin women's figures or make them muscle-bound. (Happy the dog was brought aboard to attract children.)

[1] (It should be noted that dancer and rock climber Bonnie Prudden was teaching fitness as early as the mid-1940s and that her meeting with then-president Dwight Eisenhower led to the creation of President’s Council on Youth Fitness (now the President's Council on Fitness, Sports and Nutrition).

Hooker adds, “Nobody had as much influence on the fitness industry at Jack. He was revolutionary and led the way in everything from fitness TV shows to exercise equipment.”

LaLanne created most of his own equipment, including the first leg-extension machine, pulley machines, a weight-training apparatus that became known as the Smith machine, and an elastic cord he called the Glamour Stretcher. In 1959, LaLanne recorded Glamour Stretcher Time, most likely the first workout album. (His TV show is considered the forerunner of fitness videos.)

Indeed, LaLanne advocated weight training at a time when even athletes were discouraged from doing it. In an interview quoted in The New York Times, LaLanne recalled the initial reaction of doctors: “People thought I was a charlatan and a nut. The doctors were against me—they said that working out with weights would give people heart attacks and they would lose their sex drive.”

LaLanne’s many publicity stunts may have helped crystallize his eccentric public image. Here are some of the more noteworthy:

- In a feat that conjured Houdini, LaLanne swam almost 1-1/4 miles from Alcatraz Island to Fisherman's Wharf in San Francisco while handcuffed. Afterward, he said that the worst part about the ordeal was not being able to do jumping jacks during the swim.

- In 1974, at age 60, he repeated that feat, swimming from Alcatraz Island to Fisherman's Wharf, handcuffed, shackled, and towing a 1,000-pound boat.

- Back on dry land, at age 54, he soundly defeated a 21-year-old Arnold Schwarzenegger in a bodybuilding contest.

- In 1976, as part of the nation’s bicentennial, LaLanne swam one mile in Long Beach Harbor shackled and handcuffed and towing 13 boats carrying a total of 76 people.

- In a move that should have won him a medal from AARP, in 1994, he celebrated his 80th birthday by swimming 1-1/2 miles in Long Beach, Calif., harbor while towing 80 boats with 80 people—while also handcuffed and shackled.

While these feats arguably anticipated the extreme sports craze by 40 years, they may also have obscured LaLanne’s many other innovations. He opened what is considered America’s first modern health club in 1936, before creating the prototype of today’s gym chains in the early 1960s. “The development of fitness centers as a private enterprise actually started around the time of Jack’s TV program,” says Hayes. “I’m sure there were some private clubs around the country, but they didn’t interest the masses.”

A Holistic Approach to Fitness

One of the distinctions between LaLanne’s concept of fitness and some of his descendants was that his approach was holistic. LaLanne often emphasized that chemical food additives and drugs contributed to making people mentally and physically ill. “Jack was pure in his motives and what he put in his body,” explains Missett, “and he was trying to take that message to the masses, not just to people who wanted to compete in bodybuilding contests. He spoke against the constant intake of alcohol and said that smoking was bad for you, which in the 1950s was the opposite of the public image.”

Another thing that separated LaLanne from the pack of latter-day fitness gurus was his emphasis on fitness for health rather than for cosmetic reasons, as well as the perils of overly processed food and the nation’s high-fat diet.

Most important, he believed that the country's overall health depended on the health of its people, and that physical culture and nutrition would be America’s salvation.

Hooker claims that LaLanne’s influence extended into the area of exercise research. “You’d look at him and want to know exactly how exercise enhanced health, to quantify its benefits. In a way, he helped kicked off the exercise research industry.”

Gradually, LaLanne’s accomplished were appreciated and he began to be recognized as a fitness icon. Later, his expertise was solicited by politicians such as Schwarzenegger, who asked LaLanne to head his Governor’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports.

“We brought him into meetings as a special advisor,” explains Hayes, “to plan various programs, such as strengthening school food programs and the creation of a presidential award for physical fitness. He would publicize these on his show.”

LaLanne Focused on Helping Future Generations Live Healthier Lives

Beyond his activity as fitness prophet, LaLanne was a prescient amateur sociologist; he looked into the near future and saw an America moldering at desk jobs and strung out on junk food. And he didn’t hesitate to call people on it. “He would always be upfront with people about their need to get in shape, exercise and eat better,” says Missett. However, Hooker says, “He never denigrated anyone and always spoke with hope and optimism.”

Missett recounts one memorable drive she had with LaLanne and his wife: “We were going from Lake Tahoe to Reno, on behalf of the [California] Governor’s Council, and the whole time Jack spoke vehemently about the fact that people were getting fat and there would be dire consequences for the nation.”

Hooker also attests to LaLanne’s foresight: “He helped support and publicize many youth-related projects for the Governor’s Council during my time there, from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s. He had a passion for kids. He focused on younger generation and getting them to start a fitness program that would sustain them through life.”

At a time when the public awareness of the importance of fitness and nutrition has never been higher, so has the incidence of obesity, most disturbingly among children. Hooker explains that, “The issue is there are so many environmental and social challenges to being active and eating healthily. We’re always going to need champions, and Jack was the champion of champions in that regard. He first made us aware of what we should do, and it’s up to us to do it.”

__________________________________________________________________________

Jim Gerard is an author, journalist, playwright, and stand-up comic. He has written for the New Republic, Travel & Leisure, Maxim, Cosmopolitan, Washington Post, Salon, Details, New York Observer, and many other magazines. For more information, visit his site at www.gangof60.com