By Megan Senger

Sustained neck extension, full range-of-motion squats and loading of the cervical spine. Are they harmful, or healing moves?

While each raises concerns of risk for potential injury, these movements do show up in certain advanced yoga poses. And some experts argue that—with proper experience and warm-up time—otherwise questionable or “contraindicated” movements can be healthy for a yoga student’s body. Read on to discover more about the biomechanics of advanced yoga postures that might raise concerns in the eyes of fitness professionals.

All Poses in Their Place

Commercial yoga companies frequently choose complex and contorted yoga poses (like the ones discussed below) for their brochures and marketing tools. However, advanced postures like these have no place in a beginner yoga practice, all of our experts emphasize.

“Just as a trainer wouldn’t start someone on certain exercises until they were strong enough, yoga teachers shouldn’t teach a pose unless the student has sufficient range of motion, strength and control to do the pose properly,” says Lori Rubenstein, M.App.Sc., D.P.T., a yoga instructor and doctor of physical therapy who teaches in the yoga therapy program at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, Calif. She encourages advanced postures only if “the student has trained properly and worked up to them.”

Nevertheless, fitness professionals may still wonder how certain postures can be safe, even for the advanced, warmed-up yoga practitioner. Our experts weigh in.

King Pigeon Variation I (sometimes called one-legged pigeon; Sanskrit name: eka pada rajakapotasana I)

The fitness controversy: Trainers may be concerned with torsional force on the front (i.e., bent) knee that could potentially damage its lateral structures.

The yogic perspective: This pose only presents concern if the student moves the front foot too far forward and increases the angle between the upper and lower leg too much, says Rubenstein.

To ensure adequate flexibility in the external rotators of the hip joints, students should be guided gradually into this posture by slowly improving range of motion (ROM), notes Rebecca Reed-Jones, Ph.D., a biomechanist, yoga teacher and current director of the Stanley E. Fulton Biomechanics and Motor Behavior Laboratory at the University of Texas in El Paso.

Practitioners should also “actively dorsiflex the front foot, aligning the ankle mortise joint with the shin, which then limits lateral motion at the knee,” says Robin Armstrong, D.C., a chiropractor, yoga therapist and trainer of yoga teachers based in Vancouver, B.C. (The ankle mortise joint is the bony archway made of the talus—the “ankle bone”—and the bony prominences of the tibia and fibula on either side.)

Unique benefits: This posture relieves the strain of a sedentary lifestyle and elongates the psoas and rectus femoris of the back (straight) leg, says Armstrong. Plus, it focuses on the frequently neglected flexibility of the external rotators, deep flexors and lateral muscular structures of the hips and thighs, adds Reed-Jones.

Modification: The student could position the heel of the front foot closer to the groin, says Armstrong. “You may also prop up the opposite hip [i.e., of the bent leg] with a block, blanket or towel to bring the pelvis level and to avoid overly loading the front knee,” she adds.

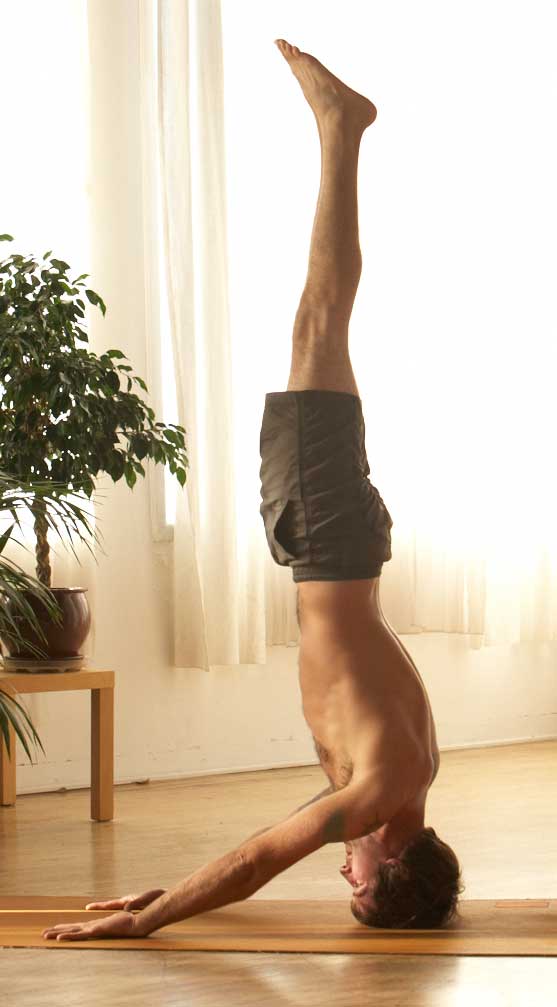

Advanced Headstands: Tripod Headstand (salamba sirsasana II) and the Ashtanga-style Palms-up Headstand (mukta hasta sirsasana B)

The fitness controversy: Unlike the more robust bones of the lower back, the cervical spine (c-spine) may not be able support the body’s weight without a high risk of injury or wear.

Should the Cervical Spine Be Loaded?

“Headstands provide us the best opportunity to load the spine and help improve bone density,” argues chiropractor Steven Weiss. He cites studies of African women who regularly carry heavy loads on their heads (such as jugs of waters) throughout their lives. These women, he says, tend to have excellent posture and bone density.

But not everyone agrees. “The architecture of our head and neck is such that it is made to float and move, not to bear weight,” notes Robin Armstrong, who is also a chiropractor. She expresses concern that yoga practitioners may also inelegantly fall out of a headstand, exposing the neck to injury associated with forced flexion or another awkward movement of the c-spine.

Ultimately, the definitive answer as to how much c-spine loading is a bad thing may be hard to determine. “A study of potential injury from headstands would have to remove the variable of good and poor alignment, which, in my opinion, would be nearly impossible,” Weiss says. Theories aside, he emphasizes that advanced headstands should only be attempted by students who already have a “mastery in retaining alignment in more basic inversions [first].”

The yogic perspective: Generally speaking, a yogic headstand puts very little load on the head and neck. Up to 90 percent of the body’s weight is borne by the muscles of the upper body (shoulder, chest, arms and back), especially when the hands and forearms are kept close to the head (as discussed in the April issue of ACE Certified News).

Even when the hands move farther away from the head, as in tripod headstand, the upper body still takes a lot of the load, explains Reed-Jones. “By having the hands on the ground [and actively pressing down with the palms], you are using the triceps and deltoids to direct a lot of the weight off of the c-spine,” she explains.

But in the much more advanced, arms-extended posture of palms-up headstand, less weight can be borne by the upper-body musculature. However, Steven Weiss, M.S., D.C.—a chiropractor, yoga instructor and yoga teacher trainer with AlignByDesignYoga.com who is based in Sarasota, Florida—argues that extra c-spine loading is not necessarily a bad thing, provided that the headstand is performed by an advanced practitioner with impeccable technique and alignment. He believes that this type of c-spine loading “could potentially be beneficial for both bone density and health.” (See sidebar, “Should the Cervical Spine Be Loaded?” for more on this topic.)

Of course, few people in our world of forward-rounded postures have exceptional spinal alignment. Therefore, most headstands should only involve a very experienced practitioner with flawless alignment, above-average core strength and years of preparatory work.

Unique benefits: Headstands allow blood to be directed toward the upper body via gravity, preventing varicose veins and edema in the legs, explains Reed-Jones.

Modification: To modify a tripod headstand, “keep the hips and knees flexed and place the knees on the elbows,” says Reed-Jones. “This allows you to align the spine correctly, but does not introduce the instability of the fully extended pose.”

Extended Fish Pose (uttana padasana)

The fitness controversy: Moving into the end range of neck extension may lead to injuries of the cervical spine.

The yogic perspective: To stay safe, precise alignment is required, Weiss explains. And while “there is little weight on the head” in the legs-extended version of this posture, Weiss notes that this is not always true for other variations of the pose.

Weiss explains how to protect the c-spine: “During the pose, the throat must be drawn back and inward. The hyoid bone [a horseshoe-shaped bone in the throat region behind the chin] is drawn posterior and superior, as if the throat is ‘smiling’ up to the ears. The occiput [the back of the head] is gently lengthened superior. Less cervical curve and more chest opening should be the goal of the practitioner.”

Unique benefits: To counteract our often semi-flexed, seated postures, “extension of the vertebrae at any level is important,” says Reed-Jones.

Extending the vertebral column stretches overly tight neck flexor muscles, she says. This can improve posture and prevent dysfunctional elongation of the longitudinal ligaments of the spine that can be caused by a chronic semi-flexed posture, she adds.

Modification: “The elbows can be placed under the shoulders with the arms down [on the floor and fingers pointing] toward the hips in a tripod position,” says Reed-Jones. The student can then draw the chest upward while using the elbows and forearms as support.

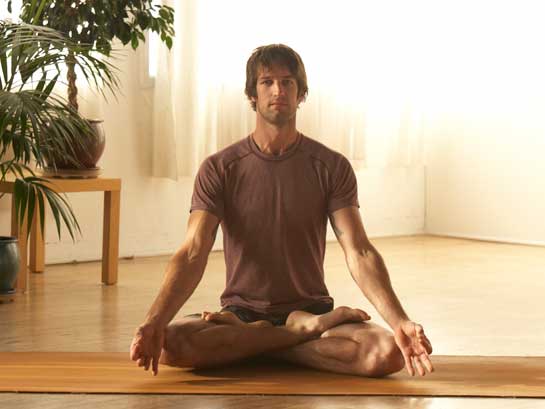

Lotus Pose (padmasana)

The fitness controversy: Lotus creates concern for ankle injuries due to a loaded “sickling” (i.e., inversion with simultaneous dorsiflexion) of the ankle joints, which may overstress their lateral ligaments.

The yogic perspective: When done properly, there is not a lot of sickling of the ankle in this posture, says Rubenstein.

Safety in lotus relies on active ankle dorsiflexion, explains Armstrong. This “limits side-to-side motion that would strain the lateral structures of the ankle,” she says. “In the final form of the pose, the ankle may slightly plantarflex, but [must] actively resist inversion by pressing the pinky toe side of the foot into the thigh to avoid strain in its ligamentous structures.”

Hip flexibility is also prerequisite, says Rubenstein. “If someone has this ROM at the hip, they should be able to place their foot such that it locks into place for stability of the pose without torquing the ankle.”

Unique benefits: “Lotus is an excellent pose to overcome the strains of sitting in a chair,” notes Armstrong. “When we sit in a chair our hips are flexed and our femurs are slightly internally rotated. Lotus pose externally rotates the femurs, elongating the muscles of internal rotation.”

Modification: “Either practice the half lotus (where only one foot is on one thigh),” says Reed-Jones, “or place a block or pillow under the buttocks to give a little support.”

Toe Stand, Bikram yoga style (padangusthasana)

The fitness controversy: The practitioner’s full body weight is supported by a single, fully flexed knee, which ostensibly puts excessive pressure on this joint.

The yogic perspective: A toe stand, using only a student’s healthy body weight, puts less load on the knee than a weight-lifting squat using 100 pounds, argues Rubenstein. And it is not a full-ROM squat that causes injury, she contends, but a lack of sufficient preparation. “The problem is when people don’t utilize their full ROM in their everyday lives or in other forms of exercise and then attempt to do poses that require full ROM.”

To safely and correctly perform the posture, the advanced student “must sink deeply into the pose with the hips below the knees to have its benefits, [but] not its potentially damaging effects,” Weiss cautions. In this way, “the weight of the pelvis is moving away from the knee joint so the force is moving away from the joint, not into it. The knee responds very well to full flexion, as long as the force of the body weight moves away from the joint.”

Unique benefits: “Students can actually improve the health of their joints by training their bodies to move through full ROM with focus and strength,” Rubenstein contends. “This can enable them to manage their daily life’s activities with less risk for injury.”

Modification: “The precursor to this pose is a Bikram-style tree pose where the person is standing and holds one foot in front of the opposite hip,” says Rubenstein. Other yoga poses, such as a yogic squat or garland pose (malasana), can be used to practice moving both knees through a loaded, full range of motion.

Harmful or Healing?

As discussed in a prior analysis of yoga postures, yoga is not inherently magical, and it cannot be said that every pose is safe for everybody, all the time.

Indeed, this caution is based in the historic meaning of yoga, notes Rubenstein. The original Sanskrit term for a yoga pose, asana, literally means “steady comfortable posture," she says. Therefore, she reasons that if the student is struggling to hold or get into a pose, “it's not a true asana” and the student should be taught a modification or a simpler pose instead.

“Just as the science of exercise has evolved over time, so has yoga and our understanding of the biomechanics within poses,” notes Armstrong.

“Traditional poses that are ‘high risk’ may be acceptable for certain students, but not appropriate for others. Just as some people may be able to get away with, for example, a lat pull-down behind the head, for many other people this would result in shoulder impingement.”

The bottom line? Yoga instructors and fitness professionals alike must pay attention to alignment—and ensure students practice patience when learning new yoga moves.

____________________________________________________________________

Megan Senger is a writer, speaker and fitness sales consultant based in Southern California. Active in the exercise industry since 1995, she holds a bachelor’s degree in kinesiology and English. When not writing on health and lifestyle trends, techniques and business opportunities for leading trade magazines, she can be found in ardha uttanasana becoming reacquainted with her toes. She can be reached at www.megansenger.com.