By Jonathan Ross

A growing body of research is demonstrating that how we think about food—not just what we eat—may hold the key to lasting weight management. Learn how the brain perceives the differences between healthy and indulgent foods, as well as its response to artificial sweeteners, and how you can use this information to help your clients better understand their relationships with food.

Did you know that what we believe we are eating and what our brain thinks we are eating dramatically affect the body’s response to what we eat? Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that certain foods may actually promote addictive responses in our brains. Unfortunately, countless experts still promote the overly simplistic approach of a “calorie is a calorie” and that the energy-balance equation (calories in vs. calories out) is the only consideration necessary for weight management. The more we learn about our intricately connected brains and bodies, however, the more outdated these approaches become.

Mind Over Milkshakes

While it’s true that we are what we eat from the perspective of what the cells of our bodies are constructed from, when it comes to how our body reacts to, processes and uses the foods we eat, a growing body of research is suggests that we are, in fact, what we think we eat.

For example, a research team from Yale University fed the exact same (360 calorie) milkshake labeled as either “indulgent” (620 calories) or “health conscious” (140 calories) to 46 study participants, who consumed each shake one week apart. To lend credibility to the “different” shakes used in the study, the researchers hired a graphic design team to produce realistic-looking labels to be placed on each of the two “different” shakes (Crum, 2011).

Researchers measured the subjects’ ghrelin response after each shake was consumed. Ghrelin is a hormone that rises to stimulate hunger when it is time for us to eat. (It’s opposite is leptin, which tells us we are full and to stop eating.)

The subjects’ ghrelin response differed significantly after each shake despite the fact that they drank the same shake—only the labels (and thus, the subjects’ perception of each shake) had changed. When participants consumed the “indulgent” shake, their ghrelin levels experienced a significantly steeper decline than when they drank the “health conscious” shake. Thinking they had indulged led them to feel more satisfied for longer (and become hungry later) than when consuming the supposedly healthier shake.

These findings suggest that the psychological mindset of sensibility while eating may actually dampen the effect of ghrelin.

The implications of this are significant. Grocery store shelves are loaded with products sporting many health claims on their labels, some of which may be misleading or even completely false. The combination of unhealthy nutrients with healthy proclamations may be especially dangerous. Not only is the product itself unhealthy, but the mindset of sensibility might correspond to an inadequate suppression of ghrelin, regardless of the actual nutrient makeup.

In other words, if someone believes they ate something healthy, they’ll likely become hungry again sooner, irrespective of whether or not the food they ate was actually healthy.

Does Sweet to the Brain = Fat on the Body?

Another team of researchers from Purdue University explored what happens when you take away the calories that the brain expects when it senses a sweet taste. Sweet taste predicts a certain caloric content and expectation in the brain. Non-caloric sweeteners apparently disrupt this relationship and may lead to excessive calorie consumption through two mechanisms: increased food intake or diminished energy expenditure. If “sweet” hits the tongue, but there are no calories coming in with it, the brain appears to send a signal to “keep eating” to retrieve the calories it expects. Alternatively, if the brain perceives that not enough calories have been consumed to support activity, it may discourage physical activity to save energy. The Purdue researchers found that reducing the correlation between sweet taste and the caloric content of foods using artificial sweeteners resulted in increased caloric intake, body weight and adiposity in rats (Swithers and Davidson, 2008).

A sweet taste in the mouth produces an insulin response in the body. Additionally, given that many artificial sweeteners are much sweeter than sugar, the insulin response may be larger than if sugar was consumed. Furthermore, anything that increases insulin levels promotes fat storage in the body (Yang, 2010).

Clearly, there is no calorie-free lunch in life. After all, we cannot realistically expect to derail one of the most finely tuned and most powerful drives in life—for food—and expect that the consequences will be positive. While many will cite the need for more research to prove that artificial sweeteners have no negative health effects, in fact the opposite is true. The burden of proof lies on manufacturers of artificial sweeteners to demonstrate that they have positive health effects and are healthier than caloric sweeteners. In the absence of these proofs, coupled with the research previously cited, the prudent recommendation would be to avoid artificial sweeteners altogether.

Can Some Foods Hijack the Brain?

In The End of Overeating, Dr. David Kessler explains that the most dominant source of the power of highly palatable foods comes from just one of the senses: taste. Taste has by far the most direct connection to the body’s reward system. It is hardwired to brain cells that respond to pleasure and prompts the strongest emotional response.

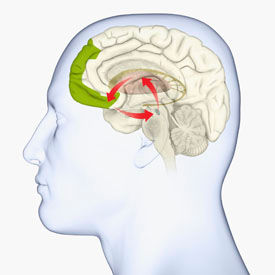

Dopamine drives desire through a survival-based capacity known as “attentional bias,” which is defined as the exaggerated amount of attention paid to highly rewarding stimuli at the expense of other stimuli. When emotions amplify reward, the drive for reward becomes even harder to control. This explains, in part, the drive many people have to seek out comfort foods when they feel stressed (Kessler, 2010).

In 2001, a study by a team of researchers at the Brookhaven National Laboratory showed that very obese people had lower levels of dopamine receptors in the reward areas of their brains than did people who were normal weight (Wang et al., 2001). This is exactly what you find with alcohol and drug addicts. The decreased dopamine activity drives overconsumption because there isn’t much reward derived from “normal” amounts of these substances.

Interestingly, obese people may not start out with an underactive dopamine response, but an overactive one. This is the initial “hook” that drives overconsumption to chase the “high.” Over time, the dopamine response progressively diminishes to the point that more “stimulus” (e.g., food, sugar) is needed to elicit the same response (Liebman, 2012).

It will take several more years of ongoing research in this area to better understand whether or not some foods can be truly addictive. However, given that many foods follow the same neurochemical pathways as other addictive substances of abuse, there will likely be at least some degree of correlation to what Dr. Kessler terms “hyper-palatable” foods. These are foods that have been over-processed and have unnaturally high levels of sugar, fat or salt, which thwart the body’s ability to self-regulate and override an individual’s good judgment, wisdom and responsibility and when making food choices.

As we seek to help our clients navigate an ever-changing nutritional landscape that, sadly, includes a growing list of extreme flavors and foods engineered to make us crave more of them by overstimulating the pleasure centers of our brains, it is essential to keep in mind the complex and powerful relationship between the mind and the body. As a growing body of research continues to demonstrate, the ability of one to influence the other cannot be underestimated.

References

Crum, A.J. et al. (2011). Mind over milkshakes: Mindsets, not just nutrients, determine ghrelin response. Health Psychology, doi: 10.1037/a0023467.

Kessler, D. (2010). The End of Overeating. Emmaus, Pa.: Rodale Books.

Liebman, B. (May 1, 2012). Food and addiction: Can some foods hijack the brain? Nutrition Action Healthletter, 3–7.

Swithers, S.E. and Davidson, T.E. (2008). A role for sweet taste: Calorie predictive relations in energy regulation by rats. Behavioral Neuroscience, 122, 1, 161–173.

Wang, G.J. et al. (2001). Brain dopamine and obesity. Lancet, 357, 9253, 354–357.

Yang, Q. (2010). Gain weight by ‘going diet?’ Artificial sweeteners and the neurobiology of sugar cravings. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 83, 2, 101–108.

___________________________________________________________________________

Jonathan Ross, a long-time leader in the fitness industry, is the author of Abs Revealed, a modern, intelligent approach to abdominal training. He was awarded the 2006 ACE Personal Trainer of the Year and 2010 IDEA Personal Trainer of the Year, and is the host of the Discovery Fit & Health series Everyday Fitness. He can be reached at www.AionFitness.com and www.AbsRevealed.com.

Jonathan Ross, a long-time leader in the fitness industry, is the author of Abs Revealed, a modern, intelligent approach to abdominal training. He was awarded the 2006 ACE Personal Trainer of the Year and 2010 IDEA Personal Trainer of the Year, and is the host of the Discovery Fit & Health series Everyday Fitness. He can be reached at www.AionFitness.com and www.AbsRevealed.com.