BY FABIO COMANA, M.A., M.S.

Since its origins as the Greek pankration in 648 BC, combat sports held modest interest among athletes until 1993, when the first modern Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) competition was staged in the U.S. under the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) brand. This full-contact, combat sport incorporates a wide variety of traditional and non-traditional fighting techniques, and is enjoying surging popularity, especially among males ages 18 to 34. Part of the attraction with MMA, which is widely considered to be one of the most grueling sports, lies in the variety of techniques fighters employ to take on their opponents.

Given its popularity, it is increasingly likely that you will encounter clients seeking your training expertise in MMA. This presents a challenge for trainers lacking firsthand exposure or experience with the sport. Doug Balzarini, an ACE-certified Personal Trainer and a strength and conditioning coach at Fitness Quest 10 in San Diego, encountered such a challenge in 2008. Armed with a keen interest, but minimal knowledge of the sport and its training techniques, he set out to develop his MMA knowledge and skill. Today, Balzarini not only trains seven professional MMA athletes, but also competes in MMA as well.

If we examine the scope of services we offer as personal trainers, we will likely notice a unique evolution. Personal training was once practiced as a pure science focused primarily upon the health-related parameters of fitness. In recent years, however, it has been evolving into an art form that not only encompasses a wider array of research-driven training techniques for health- and skill-related parameters of fitness, but also considers the individual’s psychological and emotional dimensions of fitness. The MMA athlete exemplifies the need for this new art of training. He or she needs to develop many fitness parameters, subscribe to the latest metabolic-based training methods, and devote significant time to training their mental resilience or toughness. Recognizing the importance of this evolution to the art of personal training, ACE developed the Integrated Fitness TrainingTM (ACE IFTTM Model), which serves as an effective training template to guide trainers working with individuals with traditional or unique needs, like the MMA athlete. This article will discuss how trainers can follow the training phases developed around the IFT Model to help MMA clients achieve their highest levels of success.

First Steps in Training the MMA Athlete

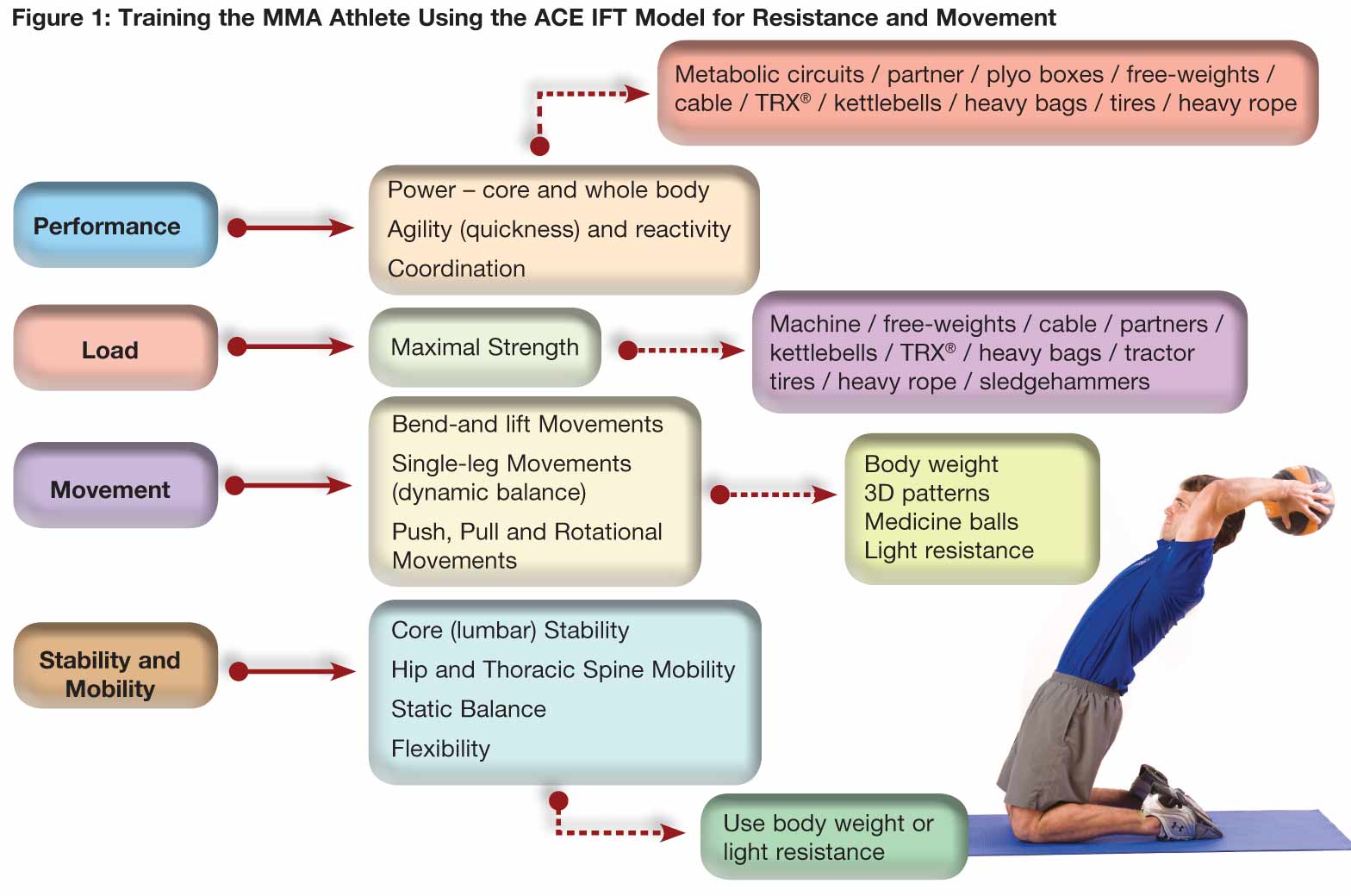

The MMA athlete will likely devote much of his or her training to the Performance and the Anaerobic Endurance/Anaerobic Power phases of the IFT model. (See February/March 2010 issue for an overview of the ACE IFT Model.) However, you should never assume that because your client has performance goals, they should automatically default to these advanced phases. A thorough needs-assessment will determine your client’s point of entry into the model.

Success in MMA demands knowledge and application of physics, kinesiology and biomechanics, particularly knowledge of movement and planes of movement (kinematics), levers and leverage, ground and reactive forces, and linear and angular kinetics (causes of movement). Integrating this knowledge into your training methods will certainly offer your athlete a strong competitive advantage. Achieving this advantage, however, is contingent upon your client possessing adequate levels of stability and mobility throughout the kinetic chain, and efficiency in their movements. Balance, bilateral symmetry, movement speed, force generation and acceptance all depend upon these elements and the MMA athlete will never realize his or her true potential until they have first attained appropriate levels of stability-mobility and can move efficiently. As a personal trainer, you may need to develop these foundational prerequisites before implementing more advanced forms of training to develop maximal strength and power.

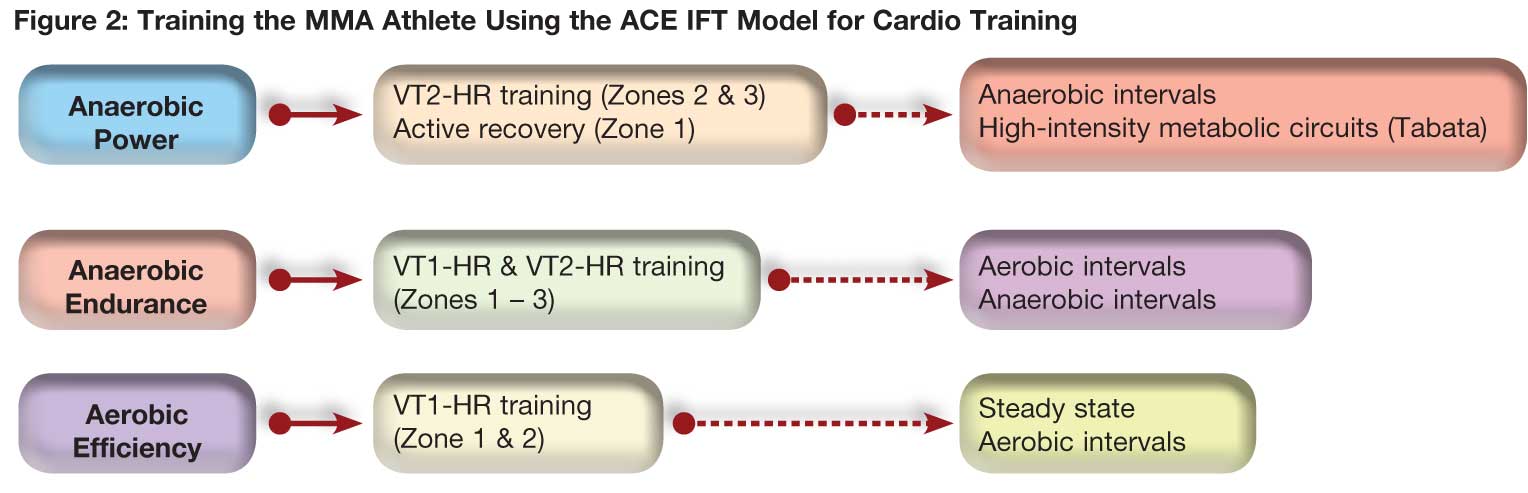

Trainers must also consider the cardiorespiratory-training program. Like other combat sports (e.g., boxing), the structure of MMA competition involves timed rounds of combat, usually between three and five minutes in duration. The event allows only brief active or passive recoveries during or between the rounds (one minute), which places extreme physiological demands upon the energy systems. These high-intensity work rates and high work-to-rest ratios can quickly deplete the anaerobic pathways, leaving the athlete vulnerable to attack. While much of the MMA athlete’s energy-system training will focus upon enhancing the anaerobic pathways, aerobic efficiency proves critical in promoting faster recoveries between rounds and during the later stages of the event. You will, therefore, need to determine if there is a need to regress the athlete’s cardio program to earlier phases initially to build his or her aerobic efficiency.

As is the case in many competitive sports, your athlete will probably work with two or more coaches, one of whom will develop and train the technical skills and fighting disciplines required for success in the sport. Additionally, he or she will likely work with a strength and conditioning coach who understands the demands placed upon the body by that sport, and seeks to prepare the athlete both physiologically and psychologically. A university-based or professional strength and conditioning coach can fulfill such a role (and can do so without necessarily needing firsthand experience within that particular sport, although it is certainly beneficial). To successfully develop your knowledge and skill sets, you must first conduct a thorough needs assessment of both the sport and the client.

Step One: Conduct a needs assessment.

- Watch the sport, take notes and ask questions.

° Gain exposure and understanding of the sport and its rules by watching how MMA athletes train and fight. Do not be afraid to gather information from top-level coaches and athletes.

- Identify your client’s fighting background, preference and style(s), and determine which styles favor their strengths and which styles expose their weaknesses.

° Draw up a list of the health- and fitness-related parameters needed to achieve success and shore up their weaknesses (Table 1).

° While fighters tend to favor specific fighting styles, they need a diverse arsenal of weapons to utilize in any position, whether to attack or defend.

– Some fighters favor “stand-up” fighting where they avoid going to the ground and try instead to fight on their feet using kicks and punches. This form draws from sports such as boxing, kickboxing, Muay Thai and karate.

– Some fighters favor “clinch-style” fighting, where they attempt to tie their opponent in a clinch and then utilize close-quarter elbows, punches, knees and stomps, or employ takedowns or throws. This form draws from sports such as wrestling, Judo, Krav Maga and Muay Thai.

– Some fighters favor “ground, ground-and-pound or grappling” fighting where they intentionally take their opponent to the ground, assume a dominant position then employ punches and submission holds. This form draws from sports such as Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Sambo, Judo and Shoot Wrestling..

Step Two: Conduct your assessments.

The ACE IFT Model offers both functional and physiological assessments trainers can utilize. Considering how many fitness parameters the MMA athlete needs, you should begin with the more relevant assessments that affect posture and movement efficiency. While you never want to overwhelm your client with assessments, select those you deem most important from the following list (refer to the ACE IFT Model for many of these protocols):

- Static postural assessment

- Bend-and-lift screen

- Push screen

- Pull screen

- Rotational screen

- Dynamic balance test or a more advanced static balance test (e.g., Y-excursion or balance test)

Next, consider selecting assessments more specific to the sport of MMA (several protocols are included within the ACE IFT Model).

- Upper- and lower-extremity strength (dead lift, squat, bench press)

- Power (snatch, clean-and-jerk)

- Aerobic capacity (VT1-HR test, 1½-mile run)

- Anaerobic capacity (VT2-HR test, 300-yard shuttle test, heavier kettlebell snatches until fatigue)

- Agility (pro-agility or hexagon cone drill)

You might also opt to devise your own MMA-specific tests to mimic many of the key movements, intensities and durations performed during an event. For example, evaluate the time to complete, or the ability to complete (to point of fatigue), a circuit (no rest) of explosive dead lifts (with your weight class) followed by a barrage of punches to a heavy bag, followed next by vertical jumps with an explosive high-knee drive, and then finishing with throw downs using a heavy bag to a dominant position. Consider devising tests that identify your client’s weaknesses and not merely their strengths (e.g., for a client lacking quickness, test his or her ability to move rapidly and reactively between markers while performing some strength feat at each marker to induce fatigue). Balzarini favors implementing four- to five-minute circuits that entail multiple MMA-specific movement patterns and intensities, and monitoring how his clients’ performance improves during the training program.

Lastly, collect any relevant psychological information on your client that will allow you to strategize mental-skills training for gaining that competitive edge. For example, the Yerkes-Dodson Inverted-U curve examines decision-making abilities and performance under different levels of arousal and anxiety. This will help you identify what level of arousal is needed for your client to train and perform optimally.

Step Three: Design your Program.

The ACE IFT Model works as a continuum. From the needs and assessment data, determine your client’s point of entry into the model for resistance/movement and cardiorespiratory training (Figures 1 and 2). Whether your client is currently competing, planning to compete in the near future or simply enjoys practicing MMA, identify your program macrocycle, mesocycles and microcycles. Although clients will ultimately devote much of their training to the Performance, Anaerobic Endurance and Anaerobic Power phases, allocate time to the prerequisite phases if needed, to build a strong foundation. Your exercises and movement patterns will most likely be generalized initially (non-MMA specific; e.g., balance, developing the five primary movement patterns, general core conditioning), but must progress to mimic MMA activities.

After your hypertrophy mesocycle to build mass (Load Phase), focus next on building maximal strength, a critical component for the MMA athlete. It is during this phase that you will have the opportunity to get creative, introducing training specificity through many non-conventional, functional-training practices and the use of equipment that mimic the sport (e.g., heavy rope, heavy bags, tractor tires, partner resistance, TRX®, kettlebells). While these movement patterns are specific to MMA, your work-to-rest ratios in the maximal strength mesocycle will not be because longer recoveries are needed to promote maximal strength. You will introduce more realistic work-to-rest ratios during the performance phase of your program. Once you have trained maximal strength, your program should now shift focus to developing anaerobic power, emphasizing explosive movements with intense bouts of work and short rest intervals. Exercises using the TRX, bodyweight training with partners, tire flips and heavy bag/dummy partners are effective training modalities. Plan to incorporate the planes and sequences of movements, and specific durations of high-intensity work that your athlete needs for his or her event. Develop metabolic circuits—three to five minutes of high-intensity work using a variety of available equipment with short (= 1 minute) active and passive rest intervals. Each circuit should include movements and techniques that mimic the fighting style of your athlete. Conclusion Training the MMA athlete requires a complex and multi-faceted approach involving modalities and progressions that can prove to be a significant challenge for most of us. Given the nature of this sport and the number of health- and fitness-related parameters needed for success, trainers should consider following a comprehensive training model that addresses these wide-ranging needs. Whether you’re working with an MMA athlete or a client with health, fitness or performance-based goals, subscribing to the ACE IFT Model will help ensure your client’s success.

_____________________________________________________________

Fabio Comana, M.A., M.S., is an exercise physiologist and spokesperson for the American Council on Exercise, and faculty at San Diego State University (SDSU) and the University of California San Diego (UCSD), teaching courses in exercise science and nutrition. He holds two master’s degrees, one in exercise physiology and one in nutrition, as well as certifications through ACE, ACSM, NSCA, and ISSN.