BY JIM GERARD

Remember that catch-phrase, “Fat is where it’s at”? We all laughed because we knew better. Fat was anathema—the biochemical fifth column that subverts our health from within (often with some not-so-conspiratorial help from our diet).

Fat was the eyesore that prevented us from squeezing into those skinny jeans and reminded us of our mortality. The flab we desperately tried to sweat, diet and liposuck away. Who could possibly see any good in it?

Well, look again. It turns out that besides the unsightly pale yellow gook that creeps out from under our wardrobe and stores excess energy, our bodies also make another kind of fat that burns through energy “like Grant took Richmond” (as my father used to say).

This “anti-fat” is called brown fat which, while it sounds even more repulsive than standard fat—it was described by one researcher as “shading from light peanut-butter to reddish-brown”—has been found by researchers reporting in the New England Journal of Medicine to have potential as a weight-loss treatment. Dr. Anne Gibson, an assistant professor in exercise science at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, calls brown fat “a special form of adipose tissue usually found in the neck1 and designed to convert food to heat.”

Dr. Daniel Smith, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of nutrition sciences at the University of Alabama, explains that science has known of its existence for decades, but has misperceived it. “They found it in newborns, but thought it dissipated as people aged. Or, if they did find it in adults, thought it was a tumor of some kind. Whereas the contrary turned out to be true—scientists doing autopsy studies of adults in the 1970s found brown fat. But it wasn’t until the 1990s with the development of molecular markers and PET scans that they could measure it more accurately.”

The Role of Brown Fat

In evolutionary terms, brown fat’s function was to keep newborn mammals’ body core temperature warm in cold environments. It is particularly effective for hibernation. Smith says that over time, scientists discovered that animals’ metabolism sped up and the “shivering response”—we shiver to generate heat—decreased because brown fat and other heat sources switched on.

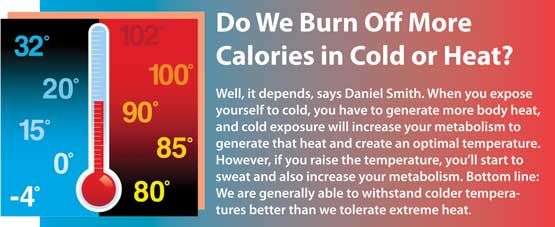

The other role of brown fat is to increase thermogenesis—to burn off excess calories. (See sidebar: Do We Burn Off More Calories in Cold or Heat?) Brown fat is unique due to its superior heat generation. “White adipose tissue is storage fat and has a low rate of metabolic activity,” says Smith. White fat burns by converting itself to energy sources only as needed, whereas brown fat is a metabolically highly active adipose tissue involved in heat production and the maintenance of body temperature. Brown fat has a lot of mitochondria [which also gives it its color]—which converts food into the energy currency of our cells, called ATP—plus it generates heat.”

Is Brown Fat the Key to Lasting Weight Loss?This is also why science—and, presumably, pharmaceutical companies—feels that it could be the magic bullet for weight loss. Dr. Francesco Celi, a clinician at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, told Time magazine that brown fat may allow a person to burn more calories with the same amount of consumption—without having to hit the gym or sweat through a workout. He emphasized that science has very few interventions that can increase energy expenditure, which is exactly the purpose of brown fat.

Smith adds that although earlier enthusiasm over the commercial use of brown fat for weight loss in the 1980s came to naught, increasingly sophisticated techniques can target its biochemical pathways and potentially increase the amount of brown fat in one’s body. “The time-frame for practical application is hard to estimate,” he says, adding that both drug companies and the NIH are currently funding research on it.

Some experts are not optimistic, their doubts fueled by the fact that it is not yet possible to know if brown fat will help regulate weight. A potential pitfall is that, barring the possibility of an ingestible brown fat product, the amount of it naturally found in our bodies declines as we age.

One hindrance to the rapid development of brown fat as a possible weight-loss tool is the problem of studying it in human tissue. Gibson says, “Much more long-term, generalized research needs to be done before we see any commercially available products using it. We’re trying to use something designed for one purpose for another [purpose] for which I don’t believe it was designed.”

Gibson believes that a brown fat pill or injection is years away and may cause counter-productive complications. A pill that could increase the activity level of brown fat could cause hyperthermia and other side effects.

Ironically, although brown fat may prevent obesity in children, the fatter we get as a society and the more insulation we have, the less we need to produce heat and, thus, the less we’ll rely upon brown fat. In fact, one study showed that one’s body mass index was inversely proportional to the activity level of their brown fat. So far, the only adults known to have appreciable amounts of brown fat are those who have certain types of cancer, hyperthyroidism or other conditions that stimulate its growth.

For all of our aversion to fat, it seems unlikely that many people would make that trade—a potential miracle fat burner

for a dreadful disease.