BY TODD GALATI, M.A.

This is the fourth article in a four-part series covering the new ACE Integrated Fitness Training Model. You can review the previous articles here: Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

The previous three articles in this four-part series provided an overview of the ACE Integrated Fitness TrainingTM (ACE IFTTM) Model. These articles described how rapport is the foundation of the model, and introduced the functional movement and resistance-training phases of the ACE IFT Model as a logical system of movement-based exercise programs and modifications that can be used with any client to train for stability and mobility to improve postural imbalances all the way through to training for speed-agility-quickness and power for improved athletic performance. The following article introduces a new systematic approach to cardiorespiratory training that can be used to help any client reach his or her unique goals for health, fitness or performance in endurance competitions.

The ACE IFT Model has four cardiorespiratory training phases:

• Phase 1: Aerobic-base training

• Phase 2: Aerobic-efficiency training

• Phase 3: Anaerobic-endurance training

• Phase 4: Anaerobic-power training

Each phase has a primary training focus designed to facilitate specific physiological adaptations to exercise. Not every client starts in phase 1, as each client has a unique entry point into the cardiorespiratory training phases based upon his or her current health, fitness and goals. By utilizing the assessment and programming tools in each phase, you can develop individualized cardiorespiratory programs that can progress clients from being sedentary to training for performance in endurance events. While most clients will not go through this full progression, it is empowering to have the tools to provide these long-term training solutions.

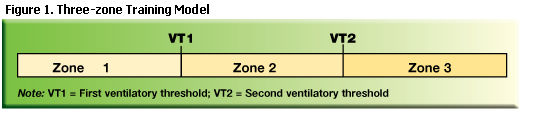

Programming in each phase is based on a three-zone training model (Figure 1). The exercise intensities in each zone are based on client-specific intensity markers that include heart rate (HR) at the first and second ventilatory thresholds (VT1 and VT2), the talk test, and ratings of perceived exertion (RPE). Traditional intensity markers such as percentages of maximal HR (%MHR), HR reserve (%HRR), or VO2 reserve (%VO2R) are not the recommended methods for monitoring cardiorespiratory exercise intensity in the ACE IFT Model, because they require actual measurement of MHR or VO2max to provide accurate individualized data for programming. Most personal trainers do not have the equipment to assess VO2max, and there is little or no reason to find a client’s actual MHR unless VO2max is also being assessed. As such, personal trainers using these traditional intensity markers must estimate MHR and VO2max using equations with large standard deviations. Exercise guidelines based upon predicted MHR or VO2max can help clients reach their goals, but they have a lot of room for error and do not account for each client’s unique metabolic response to exercise.

Three-zone Training Model

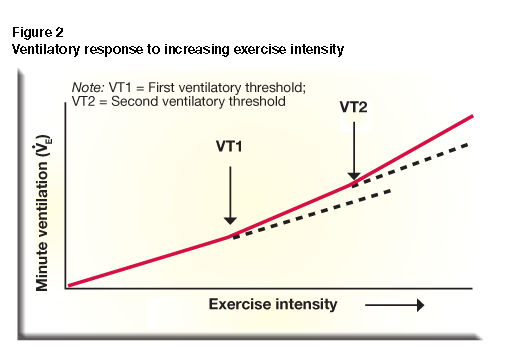

To use the three-zone training model in the four cardiorespiratory training phases of the ACE IFT Model, you must first have working knowledge of the ventilatory response to exercise. During exercise, higher levels of intensity cause an increase in respiration to allow larger volumes of air to move into and out of the lungs to facilitate increased delivery of O2 and removal of CO2. The volume of air moving into and out of the lungs in one minute is called minute ventilation VE, which increases linearly with the exception of two distinct deflection points at VT1 and VT2 (Figure 2).

Below VT1, fats are the primary fuel source, only small amounts of lactic acid are being produced, and the increasing cardiorespiratory challenge comes from a need to increase inspiration, not expiration. The body responds by increasing the amount of air inspired with each breath (tidal volume). When exercising below VT1, talking should not be challenging or uncomfortable.

At the point of VT1, the major fuel source switches from fats to carbohydrates and lactic acid begins to accumulate in the blood. The bicarbonate buffering system works to neutralize the increased lactate. This leads to increased cellular production of CO2, resulting in increased ventilation accomplished by an increase in breathing frequency. This creates the first deflection point in VE at VT1 (Figure 2). Once a client reaches VT1, he or she can still speak, but it will become somewhat uncomfortable. As exercise intensity increases above VT1, clients will still be able to speak, but it will become more uncomfortable as intensity approaches VT2.

When the buffering mechanism can no longer keep up with the extra lactate production, the pH of the blood begins to drop. This results in another increase in respiratory rate, causing the second non-linear increase in VE known as VT2. This point is generally associated with the onset of blood lactate accumulation (OBLA), designated by a blood lactate concentration of approximately 4.0 mmol/L. If exercise continues at or above VT2, blood lactate levels will rise quickly. When exercising at or above VT2, speech is not possible other than single words. This intensity at VT2 is what most fitness professionals and athletes refer to as the anaerobic or lactate threshold. Exercise intensities just below VT2 represent the highest intensity an individual can sustain for approximately 20 to 30 minutes. When an individual increases the workload performed at VT2, he or she will have improved performance.

The three-zone training model is built around these two key metabolic markers as follows:

• Zone 1: HR < VT1

• Zone 2: HR = VT1 to < VT2

• Zone 3: HR > VT2

During exercise in zone 1, talking is relatively easy and exercise can be sustained for long durations. In zone 2, clients will not be sure if they can talk comfortably and exercise can be sustained for moderate durations, depending on a client’s current fitness and level of fatigue at the start of exercise. In zone 3, speech is limited to single words and exercise can only be sustained for short intervals.

For more information about VT1, VT2 and the ability to talk in each of these three training zones, click the image above to view a video demonstration.

Assessments for VT1 and VT2

The first and second ventilatory thresholds can be accurately assessed using metabolic analyzers; however, these systems are not readily available to most personal trainers. Fortunately, field tests can be used to determine reliable heart rate values at VT1 and VT2.

The field test for VT1 is based on research that has found the talk test to be a very good marker of VT1. Below VT1, clients can speak comfortably. Once they reach VT1, they will still be able to speak, but it will no longer be comfortable. The submaximal talk test for VT1 can be conducted with clients to determine their HR at VT1 (Table 1). This value is important for programming in cardiorespiratory phases 2–4.

| Table 1: Submaximal Talk Test for VT1 (general protocol *) |

Objective

|

To measure HR response at VT1 by incrementally increasing workload in small increments to identify the HR where the ability to talk continuously becomes compromised |

| Equipment |

• Treadmill, cycle ergometer, elliptical trainer, or arm ergometer

• Stopwatch/watch

• HR monitor with chest strap (preferred)

• Phrase or paragraph to be read by client, something familiar such as the pledge of allegiance, alphabet, etc. (have printed copy if needed for reading)

|

| Pre-assessment |

• This assessment is recommended in ACE IFTTM cardiorespiratory training phases 2 through 4

• Explain protocol and obtain consent to perform assessment

• Should have pre-determined intensity jumps that will elicit a 5 bpm increase in HR

• Recital of phrase will be easy below VT1, but will become more difficult at VT1 as the ability to string 5 to 10 words together becomes challenging.

• Use caution with reading on a treadmill given the potential risk of falling

• VT1 should be reached in 8 to 16 minutes

• Goal is to record HR at VT1

• HR varies between treadmills, bikes, etc., so utilize your client’s preferred mode of exercise

• This assessment should be performed prior to any other fatiguing exercise on the test day

|

| Step 1 |

3–5 minute warm-up with HR<120 bpm (RPE of 2 to 3) |

| Step 2 |

Begin first stage of test measuring steady-state HR (aim for HR of approximately 120 bpm, or RPE = 3 to 4 on 0–10 scale). Stages should be 60 to 120 seconds long. |

| Step 3 |

Recite/read text out loud continually during last 20 to 30 seconds of each stage |

Step 4

|

Upon recital completion, ask if this task felt “easy,” “uncomfortable-to-challenging” or “difficult” (“uncomfortable-to-challenging” = VT1) |

| Step 5 |

If talk-threshold has not been reached, progress to the next stage by increasing intensity by a work rate that elicits a HR increase of 5 bpm and repeat stage length and phrase recital |

Step 6

|

Continue until “talk threshold” is reached (HR at VT1). Use a HR monitor for easier measurement. (Ideally, average HR at VT1 from 2 separate tests should be assessed.) |

| Step 7 |

3–5 minute cool-down at same intensity as warm-up once VT1 is reached and HR is recorded |

|

* For a detailed explanation of this protocol, refer to the ACE Personal Trainer Manual (4th ed.), pg. 202–204.

|

The talk test can also be used as a fairly accurate marker of VT1 in clients who have not yet performed the submaximal talk test for VT1. This is especially important for clients in phase 1, where exercise should be kept below the talk-test threshold.

The field test for VT2 is based on the premise that exercise intensities just below VT2 are the highest sustainable intensities and are excellent markers of performance. Clients can sustain exercise at or just below VT2 long enough to collect repeated heart rates to get an average HR calculation at VT2. The VT2 threshold test can be conducted with clients to determine exercise HR at VT2 (Table 2). This value is important only for clients training in phases 3 and 4.

| Table 2: VT Threshold Test (general protocol *) |

Objective

|

To measure HR response at VT2 using a single-stage, sustainable, high-intensity 15- to 20-minute bout of exercise |

| Equipment |

• Treadmill, cycle ergometer or arm ergometer

• Stopwatch/watch

• HR monitor with chest strap (preferred)

|

| Pre-assessment |

• This assessment is recommended only for clients who are deemed low-to-moderate risk and are successfully training in ACE IFTTM cardiorespiratory training phase 3 or phase 4

• Explain protocol and obtain consent to perform assessment

• Clients should be experienced with selected modality to effectively pace themselves at their maximal sustainable intensity for the duration of the assessment

• Should have pre-determined intensity that is the highest level that the client can maintain for 15 to 20 continuous minutes, as the highest sustainable intensity an individual can perform will be at or close to VT2

• Goal is to record HR at the end of each of the last 5 minutes of the assessment

• This assessment should be performed prior to any other fatiguing exercise on the test day

|

| Step 1 |

3–5 minute warm-up with HR<120 bpm (RPE of 2 to 3) |

| Step 2 |

Begin the test by increasing intensity to the pre-determined level that is the highest level that the individual can maintain for 15 to 20 continuous minutes |

| Step 3 |

Allow the individual to make changes to the exercise intensity as needed during the first few minutes of the exercise bout |

Step 4

|

Record the HR response at the end of each minute during the final 5 minutes of the exercise bout (at the end of minutes 11 through 15) |

| Step 5 |

Once HR responses for each of the final 5 minutes have been recorded, have client cool down for 3–5 minutes at same intensity as warm-up |

Step 6

|

Calculate the average HR collected over the last 5 minutes of the bout to accommodate for any cardiovascular drift associated with fatigue, thermoregulation and changing blood volume |

| Step 7 |

Multiply the average HR during the last 5 minutes by 0.95 to correct for increased intensity during a 15-minute test vs. 30-minute test—this is the HR at VT2 estimate

Example:

Avg. HR (final 5 min) = 168bpm

HR at VT2 estimate = 168 x 0.95 = 160 bpm |

|

* For a detailed explanation of this protocol, refer to the ACE Personal Trainer Manual (4th ed.), pg. 202–204.

|

Ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) correlate fairly well with this three-zone model:

- “moderate” to “somewhat hard” (RPE = 3–4, 0-to-10 scale) below VT1

- “hard” (RPE = 5–6, 0-to-10 scale) between VT1 and VT2

- “very hard” to “extremely hard” (RPE = 7–10, 0-to-10 scale) above VT2.

As such, RPE can be used by clients to track training intensities.

ACE IFT Model Cardiorespiratory Training Phases

Phase 1: Aerobic-base Training

Clients that cannot perform 30 minutes of continuous moderate-intensity exercise should begin cardiorespiratory training in this phase. This is a common starting point for many clients, especially those that are sedentary or have special needs. The most important goal in this phase is to help clients to have early positive exercise experiences that drive program adherence. Regular exercise participation will help clients see initial physiological adaptations to exercise, achieve early goals, enhance self-efficacy, and see improvements in mood, energy and stress. Many clients will progress to phase 2, while clients with limited functional capacities may continue to train in phase 1 for years.

The principal training focus in phase 1 is on helping clients that are sedentary or have little cardiorespiratory fitness to engage in regular exercise, initially to improve health and then to build fitness. Exercise in this phase should be performed in zone 1 (RPE = 3–4, 0-to-10 scale). If a client is not able to speak comfortably during exercise, he or she has gone over the talk-test threshold and exercise intensity should be decreased. Exercising in zone 1 has a high benefit-to-risk ratio for beginning exercisers. To help enhance exercise enjoyment, use different exercise modes and vary exercise intensities between RPE of 3 and 4.

Cardiorespiratory fitness assessments are not necessary in phase 1, as all exercise is performed below the talk-test threshold. In addition, poor performance on fitness tests can deflate the enthusiasm that a sedentary client has for starting an exercise program.

Progressions in phase 1 should focus on increasing exercise duration and frequency to facilitate health improvements and caloric expenditure, and should not exceed a 10 percent increase from one week to the next. Once clients are performing 30 minutes of continuous exercise just below the talk-test threshold, they are ready to move on to phase 2.

Phase 2: Aerobic-efficiency Training

Clients that can perform 30 minutes or more of continuous moderate-intensity exercise and are not currently training for performance in endurance events should train in phase 2. This is the phase where most fitness enthusiasts will train for extended periods, as many fitness and weight-loss goals can be achieved in this phase, including completing a one-time event such as a half marathon.

A submaximal talk test should be conducted at the beginning of phase 2 to determine the client’s HR at VT1. This HR will be used as the marker to differentiate between exercise in zones 1 and 2. This assessment should be performed periodically to determine if HR at VT1 increases with fitness improvements. The VT2 threshold test is not necessary in this phase.

The principal training focus in this phase is on improving aerobic efficiency. This is first accomplished through increasing exercise session time and frequency. The main limitation will be the client’s available time to exercise. Training should then progress with the introduction and progression of zone 2 intervals.

In phase 2, the warm-up, cool-down, recovery intervals and steady-state exercise should be performed in zone 1 to continue building the client’s aerobic base and to allow for adequate recovery following zone 2 intervals. Low zone 2 (RPE of 5) intervals should be introduced at a HR that is just above VT1 (approximately 1 to 10 bpm). These intervals will help increase the workload performed at VT1, resulting in greater caloric expenditure and fat utilization just below VT1. Begin with relatively brief (up to 60 seconds) work intervals with a work-to-recovery ratio of 1:3 (e.g., 60-second work interval with a 180-second recovery interval). Progress these intervals to a ratio of 1:2 and then 1:1. Interval duration can also be increased, with slow progression of interval length, frequency and recovery that is no more than 10 percent per week.

As the client’s fitness increases, steady-state exercise bouts with efforts just above VT1 can be introduced. Intervals can be progressed to the upper end of zone 2 (RPE of 6), starting with a work-to-recovery ratio of 1:3, progressing to longer intervals and then moving toward a 1:1 ratio. A sample phase 2 cardiorespiratory-training program is shown in Table 3.

| Table 3: Sample Phase 2 Cardiorespiratory-training Progression |

| Training Parameter |

Week 1 |

Week 2 |

Week 3 |

Week 4 |

Week 5 |

| Frequency |

3 times/week |

3–4 times/week |

3–4 times/week |

4 times/week |

4–5 times/week |

Duration

(10% weekly increase) |

“X” minutes |

10% increase |

10% increase |

10% increase |

10% increase |

| Intensity |

Below VT1 HR |

Below and above VT1 HR |

Below and above VT1 HR |

Below and above VT1 HR |

Above VT1 HR |

| Zone |

1 |

1 and 2 |

1 and 2 |

1 and 2 |

1 and 2 |

| Training Format |

Steady state

|

Aerobic intervals |

Aerobic intervals |

Aerobic intervals |

Aerobic intervals |

Work-to-Recovery Intervals

(active recovery) |

None

|

1:2

2–3 minute intervals |

1:2

3–4 minute intervals |

1:1½

3–4 minute

intervals |

1:1

4–5 minute intervals |

Well-trained fitness enthusiasts can progress to where they are performing as much as 50 percent of their cardiorespiratory training time in zone 2. Once a client reaches seven or more hours of cardiorespiratory training per week or develops endurance-performance goals, he or she should progress to phase 3.

Phase 3: Anaerobic-endurance Training

Clients that are highly trained fitness enthusiasts performing seven hours or more of cardiorespiratory exercise per week should progress to phase 3. This phase is appropriate for clients that have endurance-performance goals requiring adequate training volume, intensity and recovery to peak for performance. Clients do not need to be elite athletes to train in zone 3, but they do need to be motivated by goals that go beyond just finishing an event.

At the beginning of phase 3, the submaximal talk test and the VT2 threshold test should be given to determine the client’s HR at VT1 and VT2. These heart rates will be used as markers to differentiate between training zones 1, 2 and 3. For example, a client with HR at VT1 = 150 bpm and HR at VT2 = 172 bpm would have the following HR training zones:

• Zone 1: HR < 150 bpm

• Zone 2: HR = 150 to 171 bpm

• Zone 3: HR > 172 bpm

These assessments should be performed periodically, to determine if HR at VT1 or VT2 change with improved fitness. For multi-sport athletes, conduct these assessments for all primary exercise modalities where the assessment can be performed (excluding the pool) as HR at VT1 and VT2 can vary among training modes.

Exercise programming in phase 3 is focused on helping clients improve anaerobic endurance so they can perform more physical work at or near VT2 for an extended period, which will result in improved speed, power and performance. Training time should be distributed as follows:

• Zone 1 = 70–80% of training time

• Zone 2 < 10% of training time

• Zone 3 = 10–20% of training time

This is the training distribution used by elite athletes in a variety of endurance sports including Nordic skiers, cyclists and runners. The large percentage of training time in zone 1 allows endurance athletes to perform large training volumes without overtraining. Training in zone 1 includes warm-ups, cool-downs, long-distance workouts, recovery workouts, and recovery intervals following zone 2 and zone 3 intervals.

The volume of training time is higher in zone 3 than zone 2 because work in zone 3 has been found to result in the greatest improvements in aerobic capacity. The least amount of work is performed in zone 2 as this intensity has been found to be hard enough to make a person fatigued, but not hard enough to really provoke the optimal adaptations seen with zone 3 training.

The frequency and focus of zones 2 and 3 are based on the client’s event goals, strengths and weaknesses, and capacity for recovery. Highly fit clients may perform two to four interval workouts per week, while clients new to this type of training may perform only one zone 3 interval workout per week. Zone 2 intervals will generally be of longer duration, but lower intensity than zone 3 intervals, while zone 3 intervals will have longer recovery intervals following work intervals to allow for recovery from these high-intensity intervals. The total volume of training (duration, intervals, etc.) should be progressed no more than 10 percent per week. Table 4 illustrates a phase 3 mesocycle for marathon training. Only clients with endurance-performance goals that involve repeated sprinting or near-sprinting efforts during endurance events should progress to phase 4 training.

| Table 4: Sample Phase 3 Cardiorespiratory-training Program: Four-week Mesocycle for Marathon Training |

| Training Parameter |

Week 1—

Increase Intensity |

Week 2—

Increase Intensity |

Week 3—

Increase Intensity |

Week 4—

Recovery Week |

| Total Training Volume |

9 hours

|

9.5 hours |

10 hours |

6.5 to 7.5 hours |

Zone 1

(~80% of volume)

3 workouts per week plus warm-up, cool-down, and rest intervals during zone 2 and zone 3 workouts |

1 time/week

Long run = 2 hours 30 min

1 time/week

90-min run (RPE = 4)

1 time/week

60-min run (RPE = 3–4 |

1 time/week

Long run = 2 hours 45 min

1 time/week

90-min run (RPE = 4)

1 time/week

60-min run (RPE = 3–4)

|

1 time/week

Long run = 3 hours

1 time/week

90-min run (RPE = 4)

1 time/week

60-min run (RPE = 3–4) |

1 time/week

Long run = 2 hours

1 time/week

60-min run (RPE = 4)

1 time/week

45-min run (RPE = 3) |

Zone 2

(~10% of volume)

1 workout per week |

3 x 5-min intervals

1:1½ work:rest ratio

60-min workout with

long warm-up and

cool-down |

4 x 5-min intervals

1:1½ work:rest ratio

70-min workout with long warm-up and

cool-down |

5 x 5-min intervals

1:1½ work:rest ratio

75-min workout with long warm-up and

cool-down |

2 x 8-min intervals

1:2 work:rest ratio

60-min workout with long warm-up and

cool-down |

Zone 3

(~10% of volume)

1 workout per week |

2 sets: 3 x 60-second intervals

1:3 work:rest ratio

10 min between sets

60-min workout with long warm-up and cool-down |

3 sets: 3 x 45-second intervals

1:3 work:rest ratio

10 min between sets

70-min workout with long warm-up and

cool-down

|

3 sets: 3 x 60-second intervals

1:3 work:rest ratio

10 min between sets

75-min workout with long warm-up and

cool-down

|

2 sets: 3 x 30-second intervals

1:3 work:rest ratio

10 min between sets

45-min workout with long warm-up and

cool-down

|

| Strength Training |

Circuit training

2 days/week

1 hour/session |

Circuit training

2 days/week

1 hour/session |

Circuit training

2 days/week

1 hour/session |

Circuit training

2 days/week

1 hour/session |

Phase 4: Anaerobic-power Training

The principal focus of phase 4 training is on helping clients with very specific goals related to high-speed performance during endurance events to develop anaerobic-power. Athletes that might perform phase 4 training include soccer athletes, cross-country runners and cross-country skiers. The underlying physiologic principle of this type of training is that if there is substantial and sustained depletion of the phosphagen stores and accumulation of lactate, the body will adapt with a larger phosphagen pool and potentially larger buffer reserves to increase the workload performed at VT2.

As in phase 3, assessments for phase 4 include the submaximal talk test and the VT2 threshold test to determine HR at VT1 and VT2. These heart rates are then used to establish training zones with total training time similar to phase 3: 70 percent to 80 percent of the training time in zone 1, 10 percent to 20 percent in zone 3, and less that 10 percent in zone 2. The big difference between phase 4 and phase 3 training is that the zone 3 intervals in phase 4 are performed at or near maximal intensity. As such, they are of very short duration (e.g., 10 seconds) and have much longer recovery periods (e.g., work-to-rest ratio = 1:10 or 1:20).

Most clients will never train in phases 3 or 4. This is due in part to the focus of the phases on training for performance in endurance events, and because zone 3 intervals are very uncomfortable, especially in phase 4 training. The training intensity in phase 4 is so great that even elite athletes will spend only a fraction of their annual training plan focused in this phase.

Recovery and Regeneration

Training should be periodized with a regular cycle of hard and easy days within a week, and a regular cycle of hard and easy weeks within a month or mesocycle. This will allow for adaptation to the demands imposed during harder training sessions and weeks. The more challenging the training program, the more important recovery becomes. It is essential to help clients understand that to achieve their goals on hard training days, they must recover on their recovery days. Always remember that your clients are not only recovering from their training program, but also from the other stressors that impact their lives, such as work, travel, family and a lack of sleep.

Learn More

For full details on the ACE IFT Model, reference the ACE Personal Trainer Manual, 4th Edition Set. In addition, gain a general overview of the model and earn 0.1 CECs by taking ACE's free, highly-rated online recorded webinar.

REFERENCES

American Council on Exercise (2010) ACE Personal Trainer Manual (4th ed). San Diego: American Council on Exercise.

Dehart, M. et al. (2000). Relationship between the talk test and ventilatory threshold. Clinical Exercise Physiology, 2, 34–38.

Esteve-Lanao, J. et al. (2007). Impact of training intensity distribution on performance in endurance athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21, 943–949.

Esteve-Lanao, J. et al. (2005). How do endurance runners actually train? Relationship with competition performance. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 37, 496–504.

Foster, C. & Cotter, H.M. (2006). Blood lactate, respiratory and heart rate markers on the capacity for sustained exercise. In: Maud, P.J. & Foster, C. (Eds.) Physiological Assessment of Human Fitness (2nd ed.). Champaign, Ill.: Human Kinetics.

Foster, C. et al. (2001). Differences in perceptions of training by coaches and athletes. South African Journal of Sports Medicine, 8, 3–7.

Hansen, A.K. et al. (2005). Skeletal muscle adaptation: Training twice every second day vs. training once daily. Journal of Applied Physiology, 98, 93–99.

Meeusen, R. et al. (2006). Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of overtraining syndrome. European Journal of Sport Science, 6, 1–14.

Persinger, R. et al. (2004). Consistency of the talk test for exercise prescription. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 36, 1632–1636.

Porcari, J.P. et al. (2001). Prescribing exercise using the talk test. Fitness Management, 17, 9, 46–49.

Recalde, P.T. et al. (2002). The talk test as a simple marker of ventilatory threshold. South African Journal of Sports Medicine, 9, 5–8.

Seiler, K.S. & Kjerland, G.O. (2006). Quantifying training intensity distribution in elite athletes: Is there evidence for an ‘optimal’ distribution. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 16, 49–56.

Sjodin, B. & Jacobs, I. (1981). Onset of blood lactate accumulation and marathon running performance. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 2, 23–26.

Sjodin, B. et al. (1982). Changes in onset of blood lactate accumulation (OBLA) and muscle enzymes after training at OBLA. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 49, 45–57.

_______________________________________________________________________

Todd Galati, M.A., is the ACE Director of Academy and serves on volunteer committees with the Institute for Credentialing Excellence, formerly the National Organization for Competency Assurance. He holds a bachelor’s degree in athletic training and a master’s degree in kinesiology and four ACE certifications (Personal Trainer, Advanced Health & Fitness Specialist, Lifestyle & Weight Management Consultant, and Group Fitness Instructor).