Type 2 diabetes* is an epidemic currently affecting nearly 30 million Americans and is projected to worsen in coming years. Moreover, it is estimated that one in three Americans are living with prediabetes, according to data from the American Heart Association. This is particularly troublesome given that heart disease death rates are two to four times higher among those who have diabetes compared to those without the metabolic condition.

There is, however, some good news, as exercise can be a powerful remedy for individuals struggling with diabetes. Indeed, individuals with diabetes who exercise regularly are likely to experience numerous benefits, including increased insulin sensitivity, decreased hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) and reduced insulin requirements. This article outlines strategies for helping your clients with diabetes perform exercise safely and effectively.

*For simplicity, we refer to type 2 diabetes as simply “diabetes” throughout this article. Please note that these recommendations are not specific to type 1 diabetes.

Common Medication–Exercise Response Interactions and Exercise Program Modifications

The medical management of diabetes may consist of a broad range of medications. As a health and exercise professional, it is critical that you understand the interaction of certain medications with the exercise response and how a client’s exercise program might need to be adjusted. In fact, given its etiology (see sidebar), my experience has been that the considerations for medication–exercise response interactions and required exercise program modifications for clients with diabetes are more striking relative to most other conditions and/or diseases. Indeed, some of the most common medications prescribed to Americans are also those likely to be prescribed to clients who have diabetes.

Mechanism of Action

Oral hypoglycemics are a class of medications commonly prescribed for individuals with diabetes. There are three major groups of oral hypoglycemics used to control blood glucose:

- ß-cell stimulants for insulin release

- Drugs to improve insulin sensitivity

- Drugs that decrease intestinal absorption of carbohydrates

ß-cell stimulants function by inciting insulin release from the pancreas. These medications are taken with meals and help alleviate excessive increases in post-meal blood glucose levels. Two common ß-cell stimulants are Glucotrol XL and DiaBeta.The latter two oral hypoglycemic categories have little effect on the exercise response.

Interactions Between Medication and Exercise Response

The transport of glucose from the blood into the muscle cell is facilitated by the transporter protein GLUT-4. These transporter proteins respond to two signals: insulin and exercise. Because of the insulin stimulation from ß-cell stimulants, when combined with exercise, there is increased potential for hypoglycemia (i.e., low blood glucose).

Modifications Required in the Exercise Program

The most important program modification for clients taking oral hypoglycemics is frequent monitoring of blood glucose values. Initially, this should include checking levels before exercise, at the mid-point of exercise and after the exercise session is over. Once it has been established how much blood glucose values typically drop for a usual exercise session, and if these changes in glucose levels are within an acceptable range, less-frequent monitoring will be required. It should be noted that it is not your responsibility to check blood glucose values. Rather, the client should bring their own testing device, which has been prescribed by a physician or endocrinologist.

The intent of this section is not to be exhaustive in its scope. Rather, it’s to highlight some of the medication–exercise response interactions/exercise program modifications that you must be aware of when working with clients who have diabetes. It’s also critical to collaborate with the multidisciplinary team of medical providers who manage your client’s condition and familiarize yourself with other relevant medications and considerations for overall exercise programming.

The Etiology of Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is largely related to lifestyle habits (a physically inactive and/or sedentary lifestyle, excess caloric intake and nutritional deficiencies) that promote insulin resistance and inflammation, which result in hyperglycemia (i.e., high blood glucose levels). Diabetes is also associated with the following risk factors: family history, physical inactivity, overweight and obesity, high blood pressure, abnormal lipids, high percentage of abdominal fat and smoking.

Overweight and obesity are common among people with diabetes. Research suggests that a 5 to 7% decrease in body weight can reverse insulin resistance, even though individuals experiencing such losses seldom reach an ideal body weight. Improvements in insulin sensitivity appear to be more related to a reduction in systemic inflammation than to weight loss per se. However, obesity management can delay the progression from prediabetes to diabetes and may be beneficial to treat diabetes, although not all forms of obesity are associated with insulin resistance.

Highly characteristic of diabetes, insulin resistance is defined as the inability of insulin to effectively promote the uptake of glucose into cells to lower blood glucose levels. In people with this disease, this resistance is combined with a relative loss of beta cells (in the pancreas) that make insulin, which makes them unable to produce enough insulin to overcome their relative state of insulin resistance and leads to elevations in blood glucose. The majority of insulin resistance occurs in skeletal muscle. While some excess glucose may be lost in the urine, the rest is usually converted into fat. Insulin resistance may be made worse by this excess fat being deposited in the visceral fat cells, liver, pancreas and other intra-abdominal sites.

While many consider type 2 diabetes less severe than type 1 diabetes, its origin is more complex. Some people have an underlying genetic susceptibility that, when exposed to a variety of social, behavioral and/or environmental factors, allows diabetes to develop. In other words, diabetes genes are triggered by a combination of factors, such as being inactive, eating poorly, gaining weight, being exposed to pollutants, and more. Although lifestyle changes can assist in the management of diabetes, many individuals also take diabetes medications and/or insulin to manage their blood glucose. Most people with diabetes are adults, but the disease has become more common among teenagers who have overweight or obesity.

Exercise Programming for Diabetes

Programming Goals

The main exercise programming goals for individuals who have diabetes are to:

- Improve insulin sensitivity and blood glucose control

- Improve cardiorespiratory fitness

- Improve muscular strength and endurance through enhancing skeletal muscle mass

- Reduce body weight (particularly reduce intra-abdominal fat)

- Decrease insulin requirements and assist with decreasing the risk of diabetic complications

Consistency in a daily routine is a major pillar in diabetes care. This regularity refers to when meals are eaten and the amount and type of food, when medications are taken, and the frequency, intensity and time (duration and time of day) of exercise. When working with clients who have diabetes, take the time to maintain regular contact with the client’s physician or other healthcare provider when you are designing or making changes to the exercise program. This will help to ensure a more consistent and appropriate treatment plan for clients.

Cardiorespiratory Exercise Training

Chronic cardiorespiratory exercise training over two to 12 months has been reported to lower HbA1C levels by 0.6%. This reduction is clinically significant for individuals with diabetes and has been linked with a 22% reduction in microvascular complications and an 8% reduction in the rate of heart attacks. Even in individuals who don’t have diabetes, regular exercise provides important benefits in terms of maintaining normal insulin sensitivity and blood glucose control. For example, it has been reported that two months of cardiorespiratory exercise training reduces fasting blood glucose levels by 6 points.

All adults, including those who have diabetes or prediabetes, should engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity cardiorespiratory exercise per week. Additionally, avoiding going more than two days in a row without exercising is important for blood-glucose management. The main rationale for exercising at least every other day is that the effects of the last bout of cardiorespiratory activity on insulin sensitivity are lost after 24 to 48 hours in most cases, depending on the type, intensity and duration of the exercise. Doing some type of muscular training at least twice per week helps make the body more sensitive to insulin and lowers blood glucose. Thus, if someone who has diabetes or prediabetes engages in cardiorespiratory exercise three or four times a week and does muscular training at least twice, their muscles could potentially maintain higher insulin sensitivity, resulting in better overall blood-glucose management.

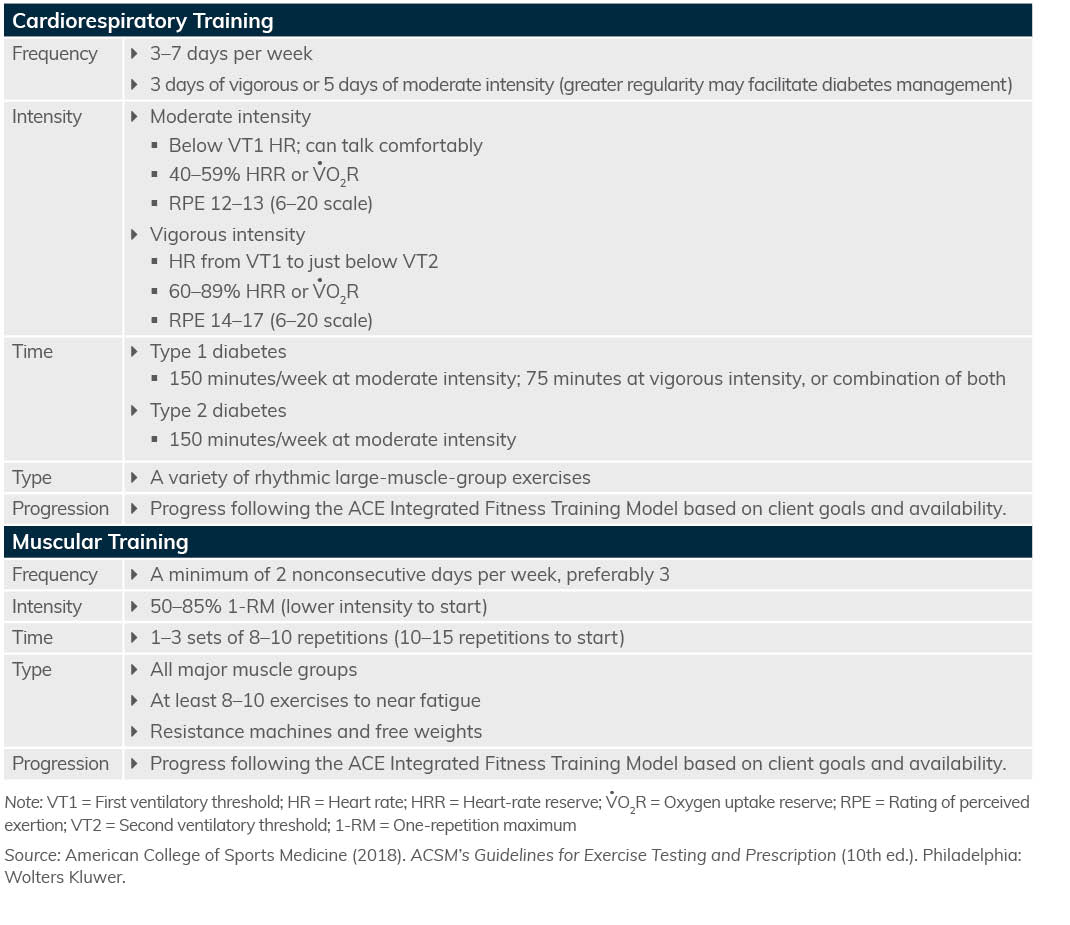

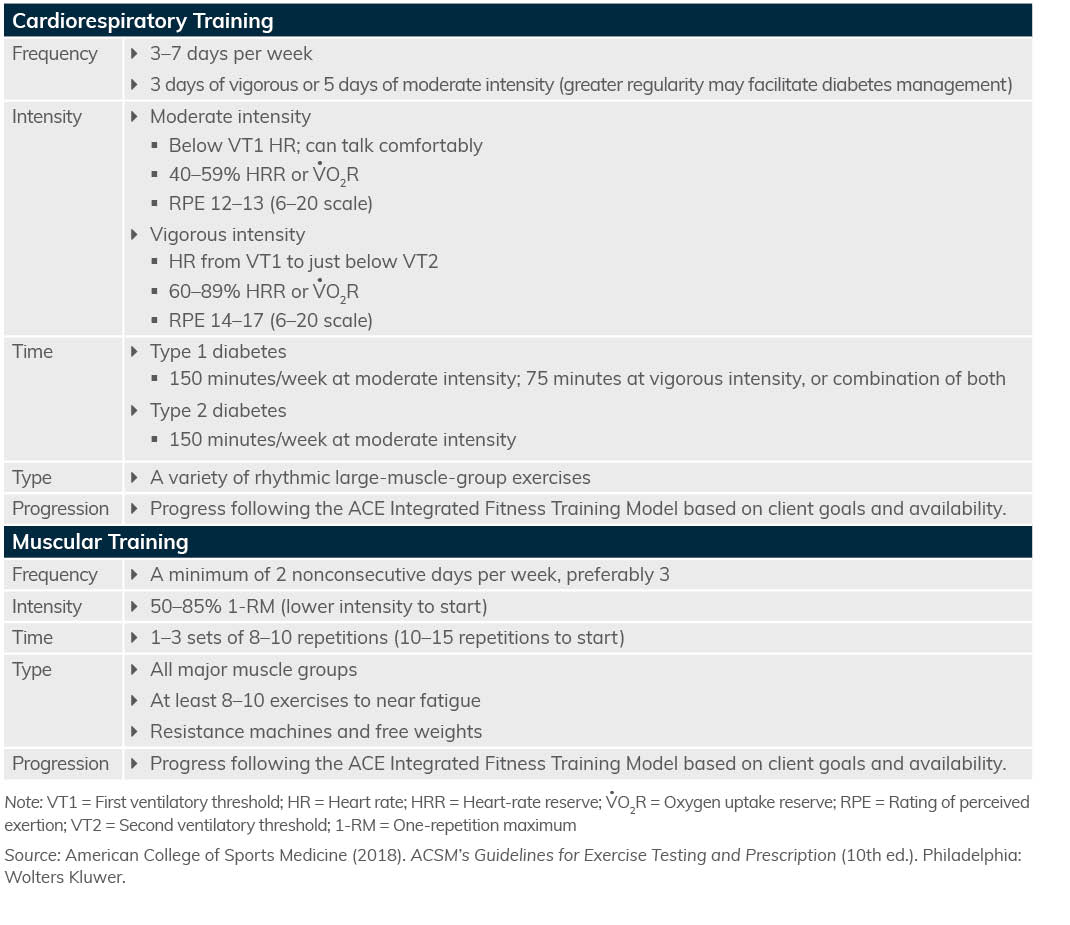

You can use the same approach for helping clients who have diabetes choose a mode of exercise as you would for a client who is an apparently healthy adult. In general, the exercise modality should be chosen by clients as something that they will enjoy, as this will serve to support their overall adherence to the exercise routine. Walking is the most common form of exercise for clients with diabetes; however, some considerations should be taken into account. For individuals who have obesity or experience diabetic complications (e.g., peripheral neuropathy), focus on minimizing high-impact, weight-bearing activities or those that require a greater amount of balance and coordination. Alternating weight-bearing activities with non-weight-bearing activities such as cycling, upper-body ergometry or swimming may enhance the safety and appropriateness of the exercise program. Exercise guidelines for clients who have diabetes are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Exercise Guidelines for Individuals Who Have Diabetes

Muscular Training

A muscular training program is essential for clients who have diabetes to assist in managing their disease and associated complications. It is also crucial for maintaining their physiological function through improving muscular strength and muscular endurance. It is generally accepted that the increased risk of diabetes with increasing age is partly due to a loss of muscle mass that negatively impacts the ability to remain recreationally active, perform activities of daily living and maintain independence.

Other benefits of muscular exercise training include improving skeletal muscle quality, improving glycemic control and insulin sensitivity, reducing HbA1c levels, decreasing intra-abdominal fat and improving the overall metabolic profile in clients with diabetes. Generally speaking, the number, type and order of exercises can be programmed much as you would for clients who do not have diabetes. Therefore, clients should perform one exercise per body part, up to a total of eight to 10 exercises, working from large to small muscle groups (Table 1).

Special Considerations

The main programmatic considerations to keep in mind involve minimizing the risks involved when individuals with diabetes exercise. In cases where a client is experiencing complications such as diabetic retinopathy, peripheral neuropathy or nephropathy, be sure to consult the client’s physician before beginning the exercise program. In these cases, the clients may need referral to a medically supervised environment if the condition limits overall exercise tolerance or if they have signs and/or symptoms of cardiovascular disease.

It is also important to attempt to minimize the risk of your client developing hypoglycemia (blood glucose <70 mg/dL) during or after exercise, as this is the most common problem with exercise. Keep in mind that exercise has an insulin-like effect on circulating blood glucose, even in the absence of blood insulin, and this effect can be enhanced if specific precautions are not taken. Accordingly, the following strategies can be used to avoid this undesirable scenario:

- Avoid exercising during times that medications are working at their peak.

- Eat one to two hours before exercise.

- Eat a snack immediately before exercise and possibly during exercise if the exercise session is of a long duration.

- Regularly check blood glucose levels before, during and after exercise.

- Know the warning signs of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia (Table 2).

Table 2: Signs and Symptoms of Hyperglycemia and Hypoglycemia

|

Hyperglycemia (>300 mg/dL)

|

Hypoglycemia (<80 mg/dL or rapid drop in glucose)

|

|

Dry skin

|

Dizziness and headache

|

|

Hunger

|

Weakness and fatigue

|

|

Nausea/vomiting

|

Shaking

|

|

Blurred vision

|

Tachycardia (fast heart rate)

|

|

Frequent urination

|

Irritable

|

|

Extreme thirst

|

Confusion

|

|

Drowsiness

|

Sweating

|

Regarding nutritional strategies, clients should consult with their dietitians or physicians on what foods are appropriate to eat before, during and after exercise. In addition, clients who have diabetes should avoid exercising late at night if possible, as this may produce low blood glucose during sleep (nocturnal hypoglycemia) and inadvertently cause a potentially emergency (and even life-threatening) situation. If late-night exercise is unavoidable, clients are advised to eat post-exercise according to their physicians’ or dietitians’ guidelines.

Proper footwear is also very important for clients who have diabetes, especially for those who have, or are at risk for, peripheral neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease. Because many of these clients may also have obesity and hypertension, maintaining adequate hydration and avoiding hot/humid environments to assist with appropriate thermoregulation and blood pressure responses to exercise will make it more likely that the client will be able to better tolerate exercise. Also, consider using lighter workloads for individuals with diabetic complications (retinopathy is a big one), as blood pressure will not increase or spike as much as it does with higher loads.

Conclusion

Working with clients who have specific health challenges such as diabetes can be highly gratifying. Regular exercise has been shown to slow the progression of diabetes, help manage its symptoms and improve overall quality of life. To learn more about this disease and how to work with individuals who have diabetes, please check out these resources:

Expand Your Knowledge

Diabetes Prevention Coaching: Become a Diabetes Coach

This course reinforces your knowledge about healthy habits and equips you to coach clients using evidence-based disease-prevention strategies that address physical activity, nutrition and lifestyle behavior change together. You’ll learn how to apply behavior-change coaching methods through realistic coaching scenarios and be well prepared to create and deliver diabetes prevention strategies, increasing your earning potential and expanding your impact by serving the growing number of people struggling with, or who are at risk for, diabetes.

Helping Clients Manage Disease Through Exercise – Course Bundle

Chronic disease can be both physically and emotionally debilitating for a client. As an exercise professional, you can make a difference during the prevention, management and recovery phases. With the Helping Clients Manage Disease through Exercise course bundle, you’ll learn how to make physical and emotional impact on clients affected by cancer, Type 2 diabetes and thyroid disease.

Diabetes Training Program Level 1 (Beginner)

This foundational level course covers the basics on how to work with clients with diabetes or prediabetes with health complications that must be managed for them to train safely and effectively. Master the basics of being physically active with diabetes or prediabetes, including types of training that are appropriate and critical, injury prevention, blood glucose monitoring, medication basics (and exercise effects), complications and exercise.