According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an estimated 35.5 million Americans (one in seven adults) live with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The prevalence of CKD is more common in older adults, as 34% of those who have been diagnosed are aged 65 or older. However, it is estimated that as many as 90% of people who have CKD don’t actually know they have it.

People with CKD have damaged kidneys that do not clean the blood as well as normally functioning kidneys. Blood and urine tests for glomerular filtration rate and urine albumin are used to detect CKD. Over time, reduced kidney function can lead to an accumulation of toxic waste and excessive fluid accumulation in the body. Other chronic conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes and obesity, are common in those with CKD. In fact, research suggests that people with CKD have a two- to fourfold increased risk for developing cardiovascular disease and, as a result, a shorter life expectancy.

Previous research has shown that people who have CKD can experience numerous benefits from exercising regularly, including slower disease progression, improved comorbidities and better quality of life. This article outlines strategies for helping your clients with CKD perform exercise safely and effectively.

CKD and Common Comorbidities

It’s important to recognize that nearly all people with CKD have other comorbidities as well. The most common chronic conditions include the following (the range of prevalence is in parentheses):

- Hypertension (55.3–62.9%)

- Musculoskeletal problems (42.2–55.3%)

- Cardiovascular disease (14.3–40.3%)

- Diabetes (21.3–35.4%)

- Mental health disorders, including anxiety/depression (19.1–30.4%)

Exercise is relatively safe for most clients who have multiple chronic conditions provided that appropriate assessment and screening is performed prior to beginning the program. The likelihood of an adverse event, although not entirely preventable, can be significantly reduced with baseline assessments, education and client adherence to established exercise recommendations. Always take the time to check in with your client’s entire medical team about any specific limitations to be aware of when designing the exercise program.

Given the strong likelihood that your client will possess multiple chronic conditions, as a health and exercise professional, you must be prepared to meet the challenge of developing a suitable comprehensive exercise program that addresses each of your client’s chronic conditions. Here are several considerations:

- The complexity of working with clients possessing multiple chronic conditions requires a thorough preparticipation screening.

- A shortcoming to our overall current healthcare model for the management of chronic conditions is that the treatment has historically been approached in a singular fashion. In fact, it has been noted that clients infrequently receive guidance from medical providers on prioritizing and managing multiple chronic conditions. As such, a critical role for the health and exercise professionals is to assist the client with developing a suitable comprehensive exercise program that addresses each of the client’s chronic conditions.

- Individuals with multiple comorbidities may possess conditions that fluctuate significantly from day to day in terms of severity. This is especially true with CKD. As such, health and exercise professionals must be prepared to accommodate an ever-changing chronic condition landscape with these clients and constantly adjust the session to best serve the client on any given day.

- Another strategy we have used with clients with comorbidities is to work on the most limiting one first (as opposed to the most serious). This approach can unlock potentials that were not present before. For instance, working on strength and posture can alleviate back pain, which can open up the ability to finish cardiorespiratory exercise sessions and thus help lower cardiovascular disease risk factors. This progressive approach allows clients to experience real progress as opposed to only seeing their restrictions.

Common Medication–Exercise Response Interactions and Exercise Program Modifications

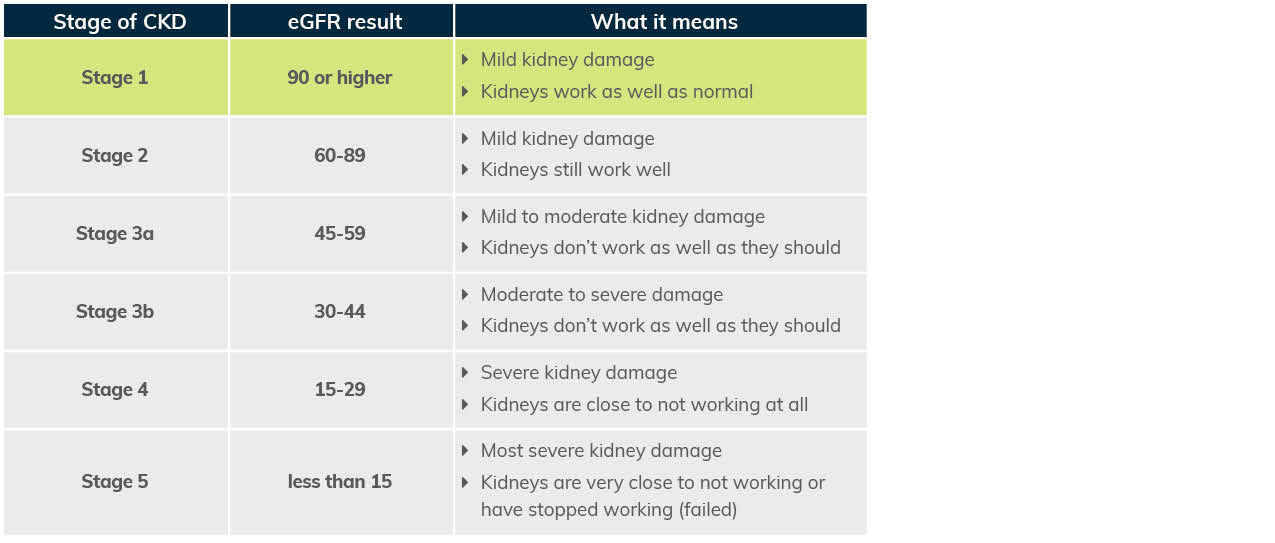

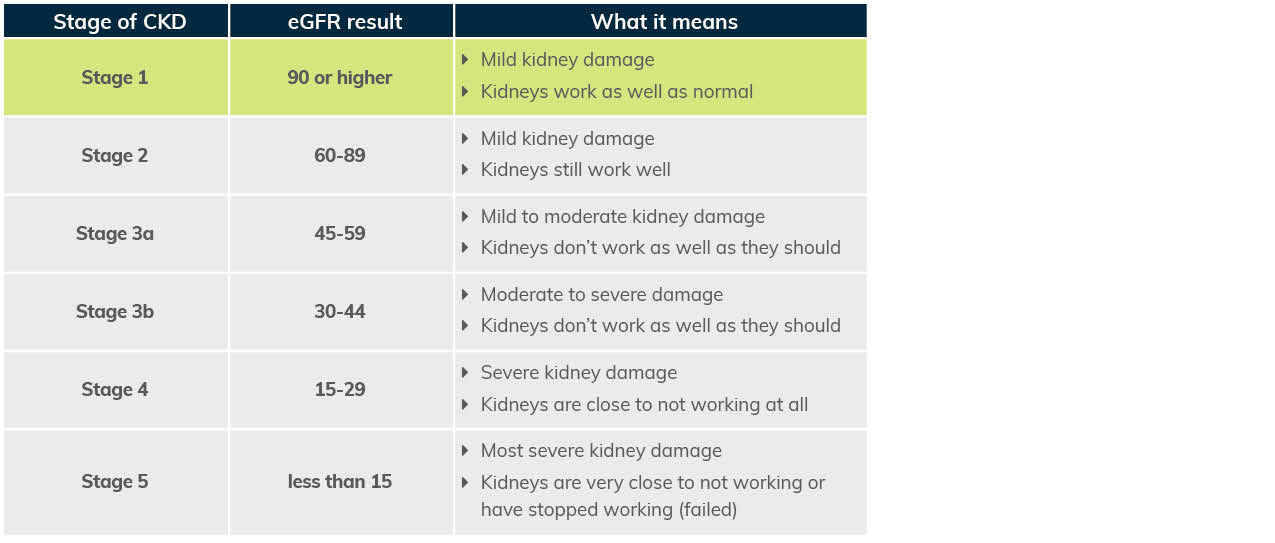

The five stages of CKD used by those in the medical field to identify the risk of disease progression and oucomes are presented in Table 1. The medical management of CKD may consist of a broad range of medications. As a health and exercise professional, it is critical that you understand the interaction of certain medications with the exercise response and how the exercise program might need to be adjusted. Indeed, some of the most common medications prescribed to Americans are also those likely to be prescribed to clients with CKD, including ACE inhibitors.

Table 1. The Five Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease

Adapted from American Kidney Fund

Mechanism of Action

An ACE inhibitor (or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor) is a medication primarily used for the treatment of hypertension, which is the most prevalent comorbidity in CKD. Common ACE inhibitors include captopril, enalapril and lisinopril. ACE inhibitors reduce the activity of the complex renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Simply put, ACE inhibitors block the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, primarily in the lungs. The molecule angiotensin II is a potent vasoconstrictor of blood vessels. Therefore, reduced production of this molecule results in relaxation of the blood vessels and lower blood-pressure values.

Interaction Between Medication and Exercise Response

Individuals who take ACE inhibitor medication have lower blood-pressure values both while resting and during exercise. However, it is the interaction between ACE inhibitors and the post-exercise blood-pressure response that requires your additional attention. An acute beneficial response to exercise is a phenomenon known as post-exercise hypotension, during which systolic blood pressure values can be reduced by 10 to 20 mmHg for up to nine hours after the conclusion of exercise. This occurs due to a persistent, but transient, relaxation of the blood vessels. The concern for individuals taking ACE inhibitors is that the combination of the reduction in blood pressure from the medication coupled with the naturally occurring post-exercise hypotension can result in excessive reductions in blood pressure. This can lead to untoward events such as dizziness and, in rare instances, syncope (i.e., temporary loss of consciousness).

Modifications Required in the Exercise Program

It is critical that clients who take ACE inhibitors consistently adhere to a gradual cool-down after each and every exercise session. One of the classic benefits of a cool-down is enhanced venous return and the prevention of blood pooling in the skeletal muscle. A gradual cool-down of five to 10 minutes of light aerobic activity helps the body to return to homeostasis and prevents excessive reductions in blood pressure.

The intent of this section is not to be exhaustive in its scope. Rather, it’s to highlight the concept of important considerations for medication–exercise response interactions and potential exercise program modifications to be aware of when working with clients who have CKD. Cholesterol-lowering and anti-diabetes medications are also commonly prescribed for clients with CKD. These categories of medications will also interact with the exercise response. Finally, it’s also paramount to collaborate with the multidisciplinary team of medical providers who manage your client’s condition and familiarize yourself with other relevant medications and considerations for overall exercise programming.

Exercise Programming for Clients Who Have CKD

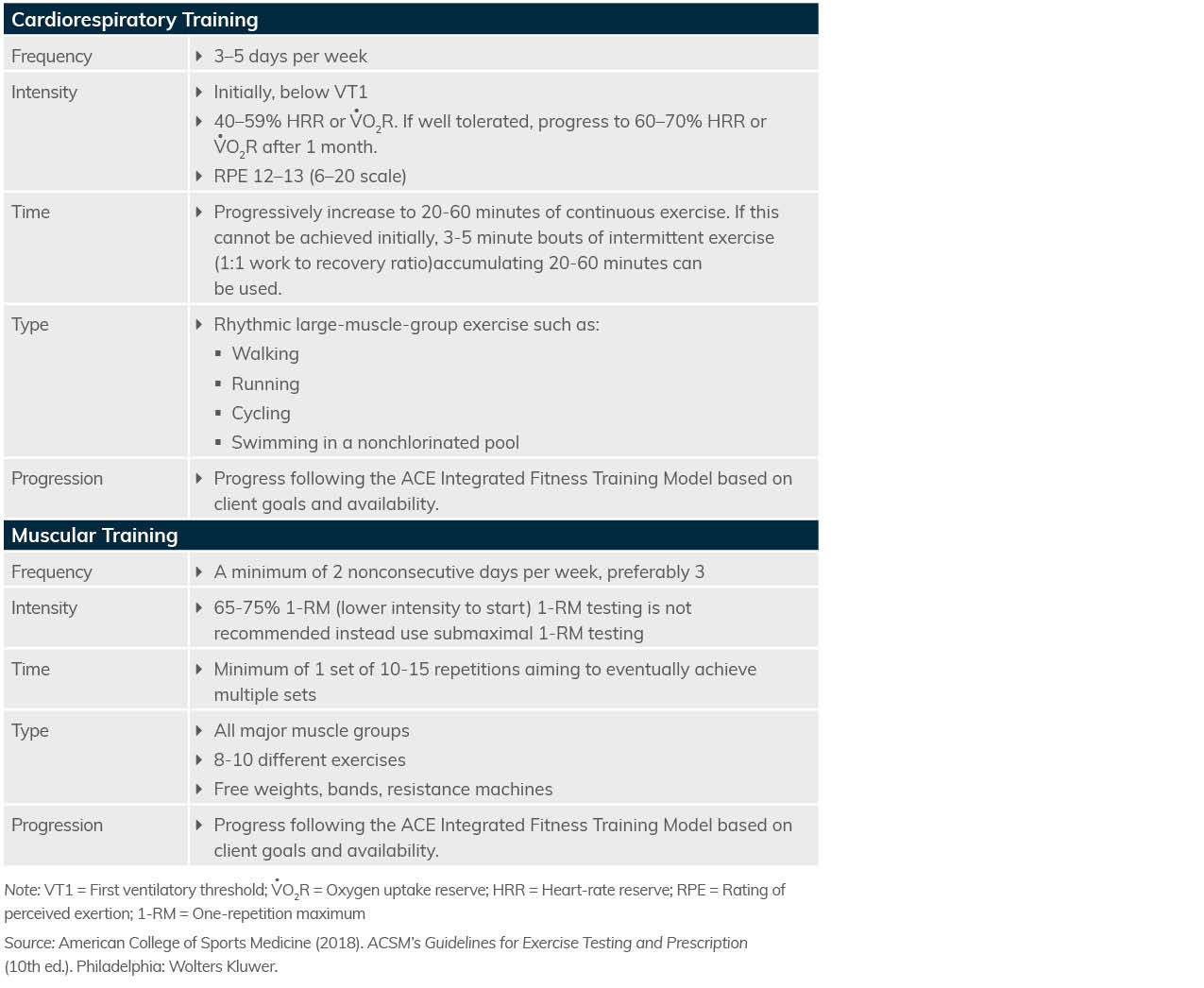

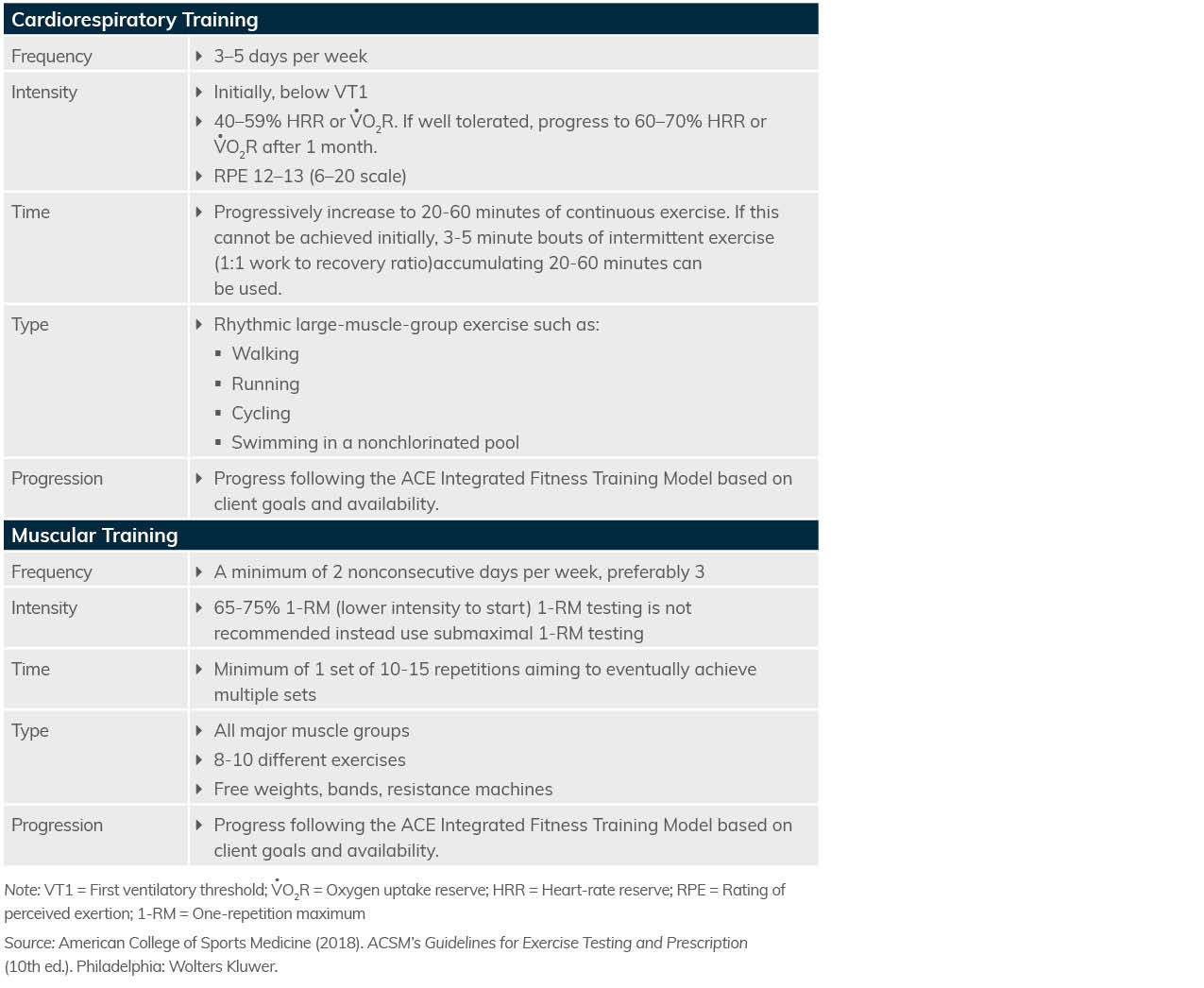

Exercise is generally well-tolerated by people who have CKD and should be encouraged. Use the exercise guidelines presented in Table 2 for cardiorespiratory and muscular training with your clients who have CKD.

Table 2. Exercise Guidelines Summary for Clients Who Have Chronic Kidney Disease

Here are some additional programming considerations to keep in mind:

- Fatigue is the most common symptom in clients with CKD and affects 70% of individuals.

- Clients with CKD are prone to exercise intolerance. For this reason, it is critical that you closely monitor initial exercise sessions to ensure all exercises are being performed correctly and are well-tolerated.

- For cardiorespiratory training, prioritize increasing exercise duration relative to intensity. For muscular training, prioritize lighter resistance and more repetitions.

- The talk test is a practical way to identify the first ventilatory threshold (VT1) and helps to provide individualization to cardiorespiratory training. Clients who have CKD typically find using the ability to talk comfortably as the easiest way to regulate their intensity and avoid aggravating fatigue symptoms throughout their exercise sessions.

- In the event your client is highly deconditioned and cannot perform continuous exercise, which is quite common with CKD clients, initial cardiorespiratory training should be performed as interval sessions of two to three minutes at an intensity at or below VT1 with an equivalent amount of rest between intervals. Gradually progress the number of interval bouts as tolerated and aim to gradually transition to continuous exercise durations of 20 to 30 minutes over the course of a few months. Consider starting with a couple of interval bouts per session and increase by one or two bouts per week, keeping in mind that every client will be different.

- Clients in the later stages of CKD may be undergoing hemodialysis. Generally, exercise should be performed on non-dialysis days. Hypotension (i.e., low blood pressure) is more likely post-dialysis, so blood pressure and/or symptoms of low blood pressure should be monitored. There will be an access point in a client’s arm for dialysis treatments; no pressure or weight should be placed on these anatomical locations.

- Peritoneal dialysis is another form of dialysis for clients in later stages of CKD. The primary consideration in these instances is for clients to drain fluid from their abdomen prior to exercise if they experience abdominal discomfort with fluid present during preliminary exercise sessions.

- Postural instability occurs with CKD and is associated with worse physical and cognitive functioning. As such, corrective and flexibility exercises are beneficial. The general frequency, intensity, time and type (FITT) approach to exercise programming used for cardiorespiratory and muscular-training program design can also be applied to flexibility exercise programming. Flexibility training should be performed two to three days each week for 10 to 15 minutes per session. However, be sure to encourage gentle, progressive stretching to avoid overstretching. Tai chi and yoga may also be effective modalities of physical activity that incorporate flexibility.

- Individuals who have CKD are at a high risk of falls. This can be problematic, as bone metabolism abnormalities (i.e., osteoporosis) tend to go hand-in-hand with CKD, which means falls are likely to also lead to fractures. Therefore, balance training and fall prevention should be a priority for your clients with CKD. However, because of their heightened risk for falls, it is important to be more conservative with balance-training exercises and progressions, and to provide more supervision and spotting.

- Providing social support and encouraging exercise in a group setting can be helpful with promoting exercise adherence.

Summary

Working with clients who have unique health conditions such as CKD can be challenging, yet highly rewarding. By understanding the condition and its multiple comorbidities, the impact that certain medications may have on the exercise response and being mindful of special exercise programming considerations, you can set your clients up for success by helping them perform regular exercise safely and effectively.