Understanding exercise intensity can often feel like solving a complex puzzle—and this holds true for both clients and professionals alike. While time and frequency are straightforward to grasp, intensity—arguably one of the most important variables—can be a stumbling block. This is where the first and second ventilatory thresholds (VT1 and VT2) come into play, offering a scientific yet accessible way to gauge how hard someone should be exercising. In this article, we simplify these often-confusing markers and explore how health and exercise professionals can effectively use them to guide clients in achieving their fitness goals safely and efficiently. Whether you’re helping a beginner find their rhythm or pushing an advanced athlete to new heights, understanding VT1 and VT2 can transform how you design and adjust exercise programs.

All exercise and physical activity guidelines include recommendations for several variables including frequency, duration, time and intensity. Most variables are straightforward and easy to understand and apply, but intensity is one variable that often leads to confusion, which can be a barrier to becoming more physically active. For example, the second edition Physical Activity Guidelines suggest that adults should move more and sit less throughout the day—a straightforward and easy-to-understand guideline. However, the guidelines also say that you should do at least 150 to 300 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 to 150 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity. At this point, things can start to feel complicated. The time ranges are clear, but how do you know how hard you are working. This is where you play a crucial role as an exercise professional or health coach, as you can help your clients understand what exercise intensity is and how it can be measured and tracked in a practical way.

What is Intensity?

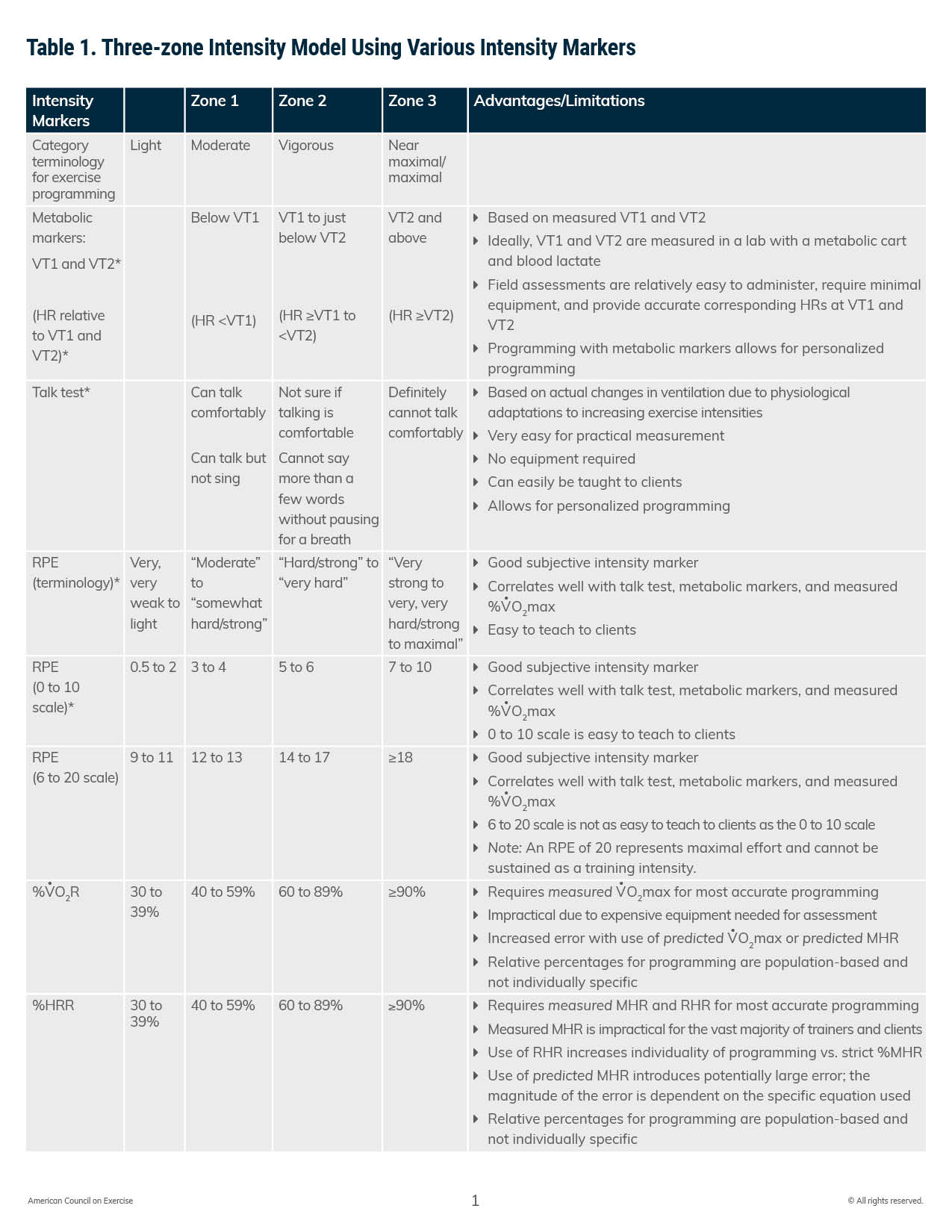

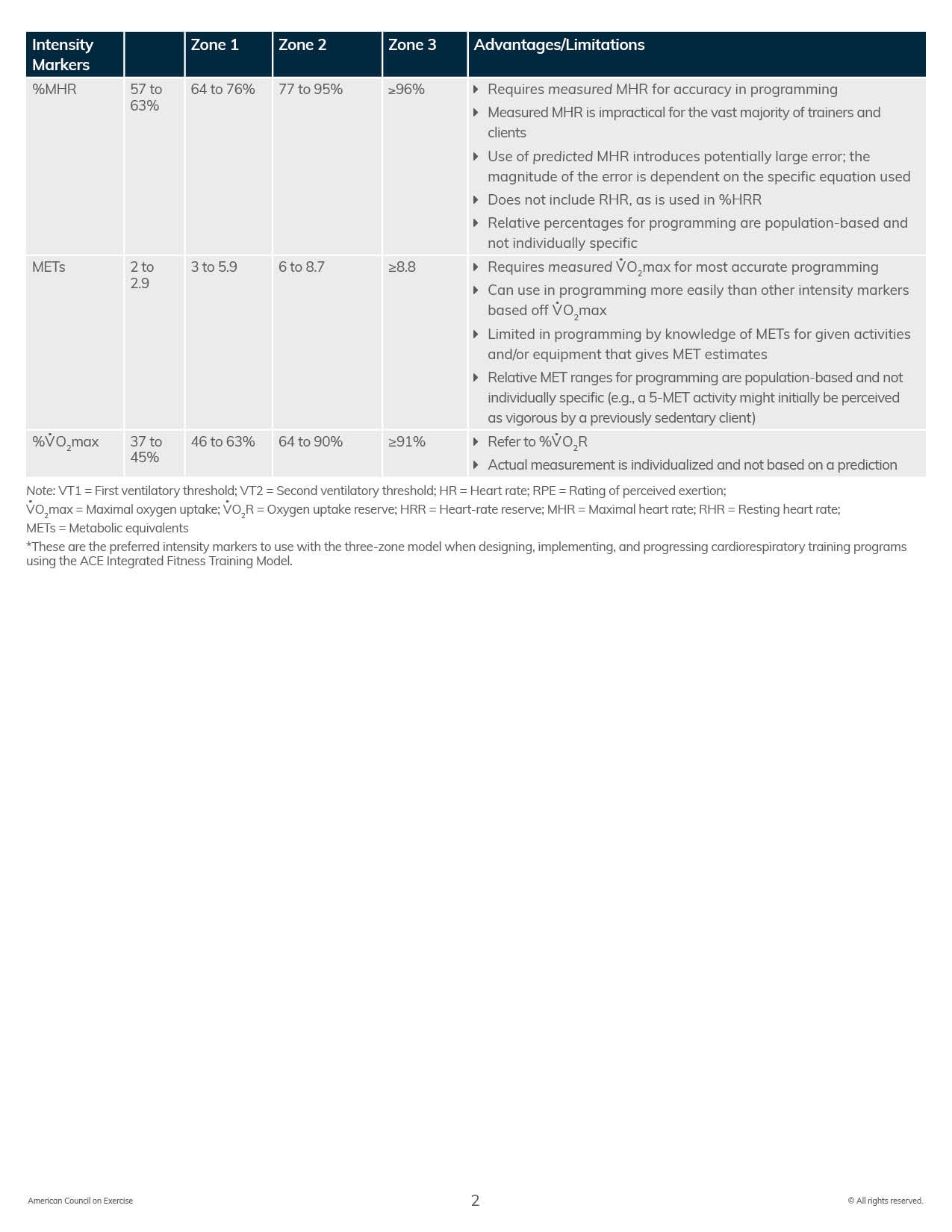

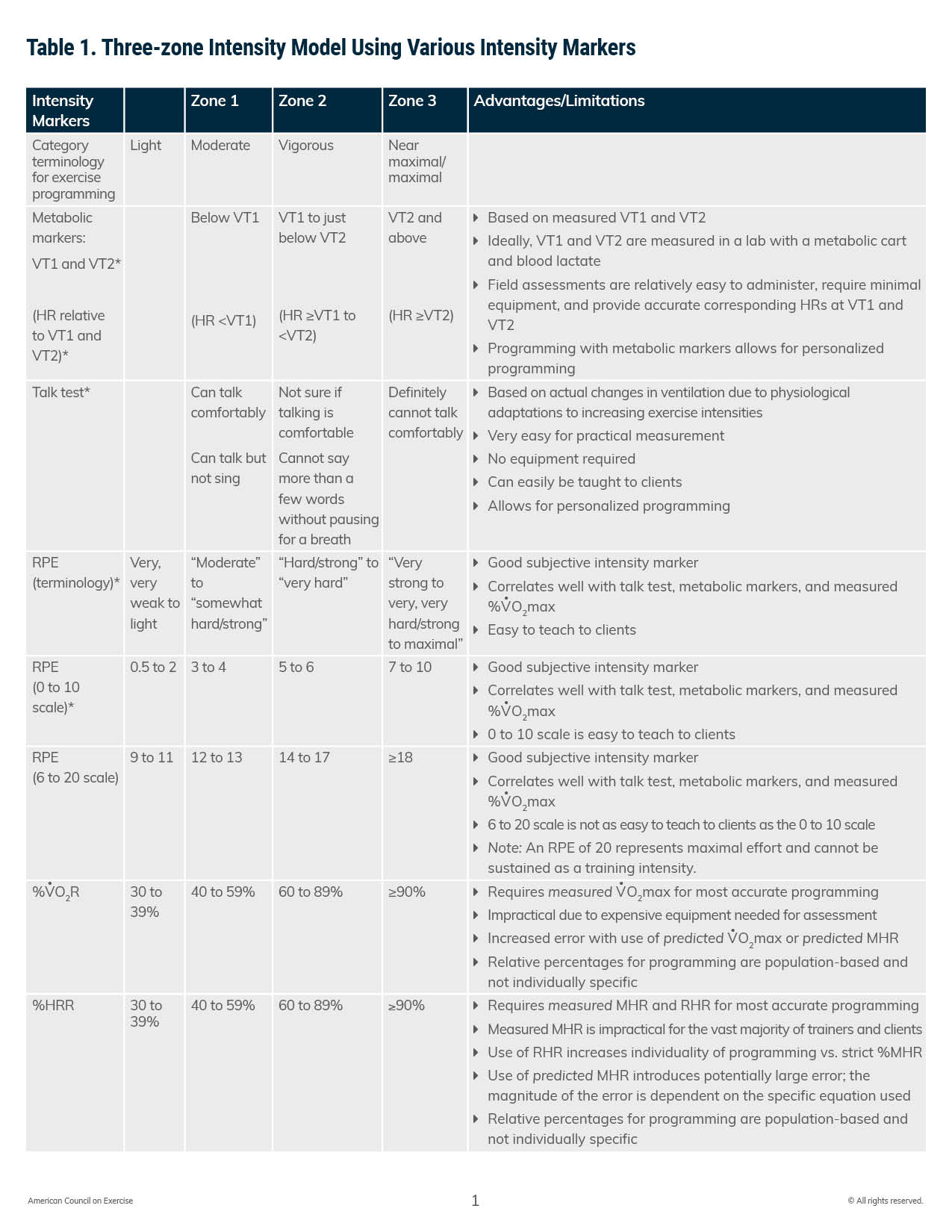

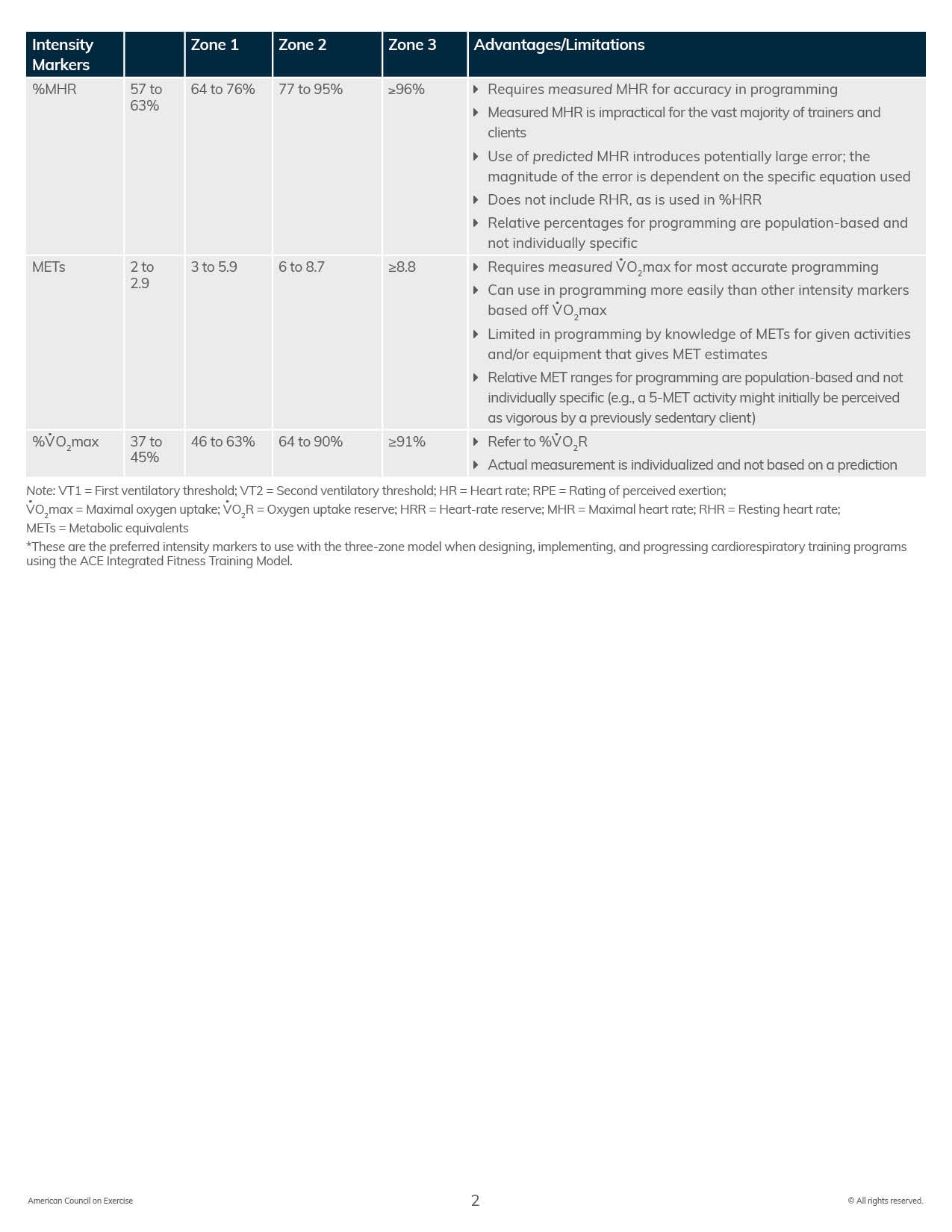

In the context of physical activity and exercise, intensity represents the degree to which a person is doing an activity, or how hard the body is working. Setting intensity parameters for exercise can help ensure that clients are achieving target levels of work to achieve desired physiological responses. There are a variety of ways to monitor exercise intensity. Some of these are subjective, some are objective, and others are based on the use of predictive equations. Table 1 identifies numerous methods for monitoring exercise intensity and discusses the advantages and limitations of using each intensity marker.

You can access and download a printable version of Table 1 by clicking on the image below.

Table 1. Three-zone Intensity Model Using Various Intensity Markers

Three-zone Intensity Model

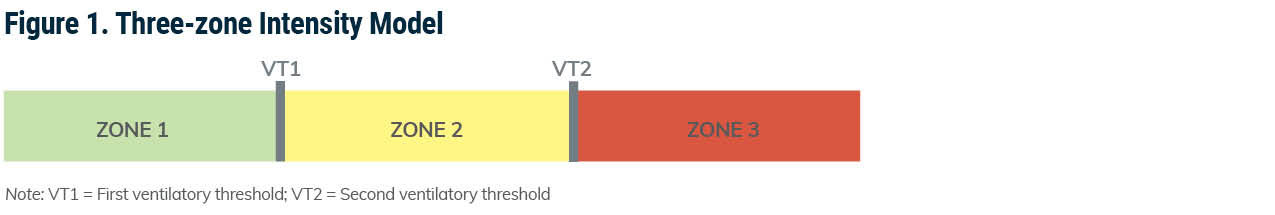

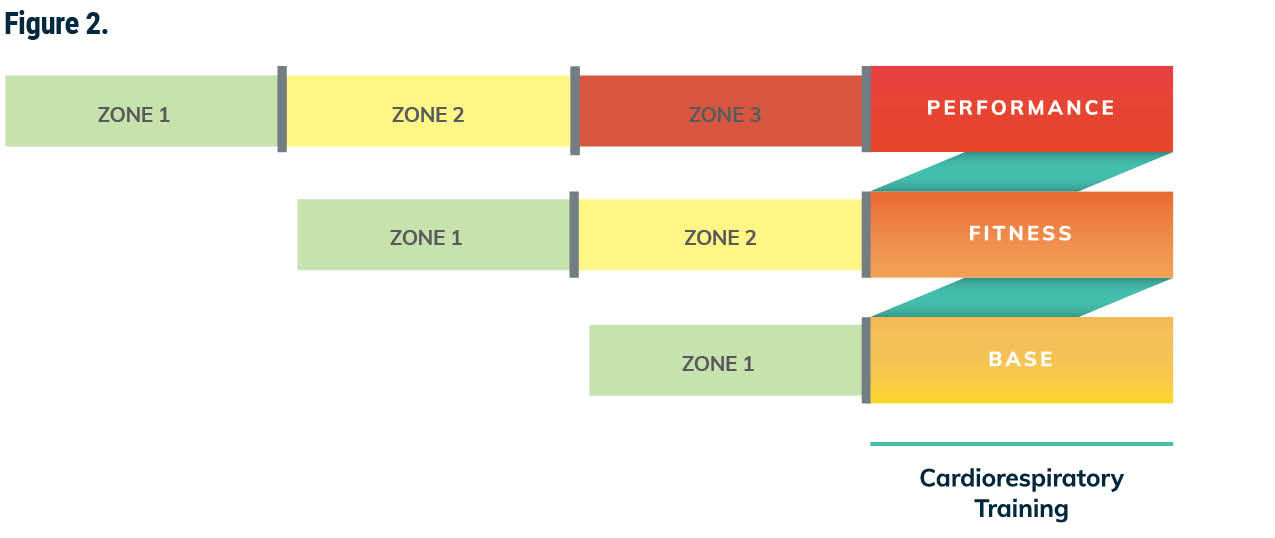

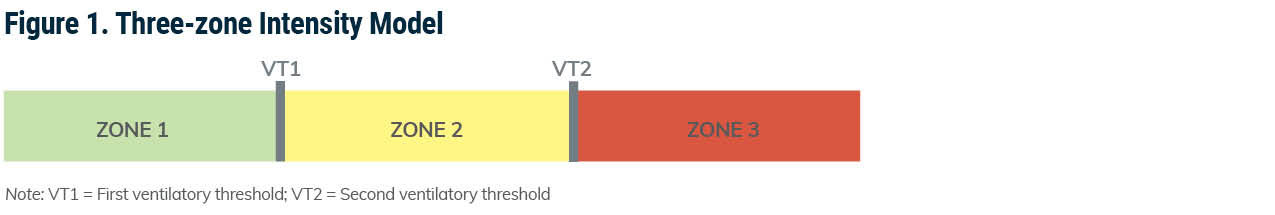

Used in conjunction with the ACE Integrated Fitness Training® (ACE IFT®) Model, the three-zone intensity model is used when designing exercise programs within each cardiorespiratory training phase. Each zone of this model is separated by a ventilatory threshold (VT1 and VT2). Zone 1 represents heart rates (HRs) below VT1, zone 2 represents HRs from VT1 to just below VT2, and zone 3 represents HRs at and above VT2.

When using the talk test to monitor intensity (more on this below), this model can be used to determine how intensely a client is exercising. Stated simply, if a client can talk comfortably, they are training in zone 1. If the client is not sure if they can talk comfortably, they are working in zone 2, and if the client definitely cannot talk comfortably while training, they are working in zone 3 (Figure 1).

Ventilatory Thresholds and the ACE IFT Model

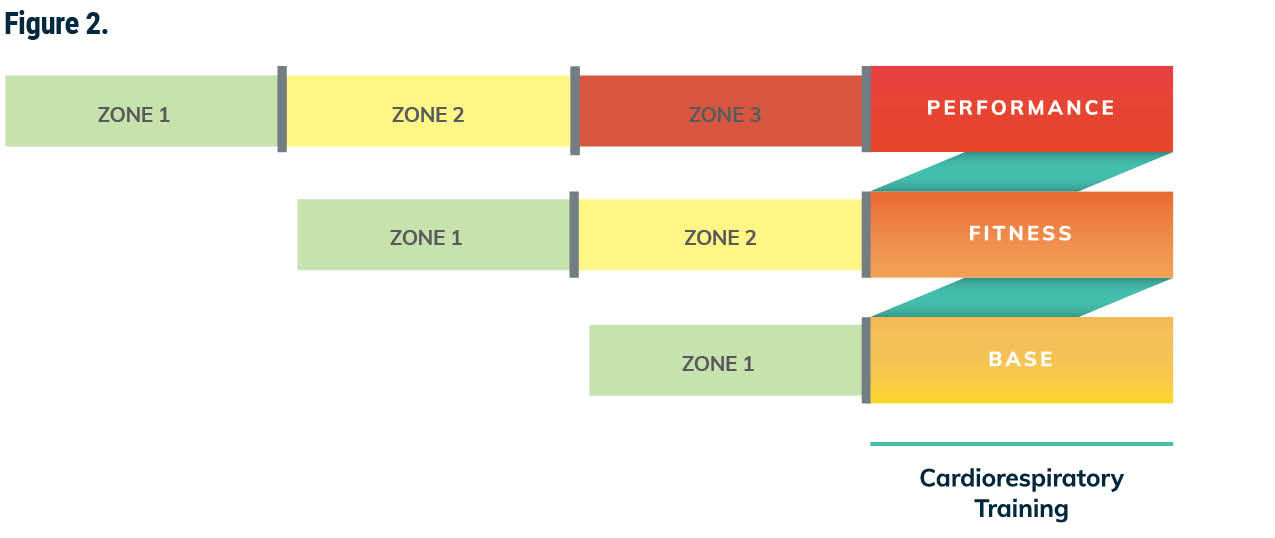

The three zones and the ventilatory thresholds work well with programming for cardiorespiratory training. In phase 1, Base Training, the exercise intensity remains below the talk-test threshold and the training focus is on enjoyment and increasing the frequency and duration of exercise bouts. Clients should remain in this phase until they can complete at least 20 minutes of cardiorespiratory exercise below the talk-test threshold at least three times per week.

In phase 2, Fitness Training, vigorous-intensity intervals are introduced that feature work-to-recovery ratios in zone 2 (at and above VT1 to just below VT2) and in zone 1 (below VT1). The training focus during this phase is to increase the duration and frequency of exercise while also increasing the intensity using intervals.

In phase 3, Performance Training, periodized training programs are used to incorporate adequate training time below VT1, from VT1 to just below VT2, and at or above VT2. In other words, during performance training, the client will exercise at intensities across all three zones (Figure 2).

What is a Ventilatory Threshold?

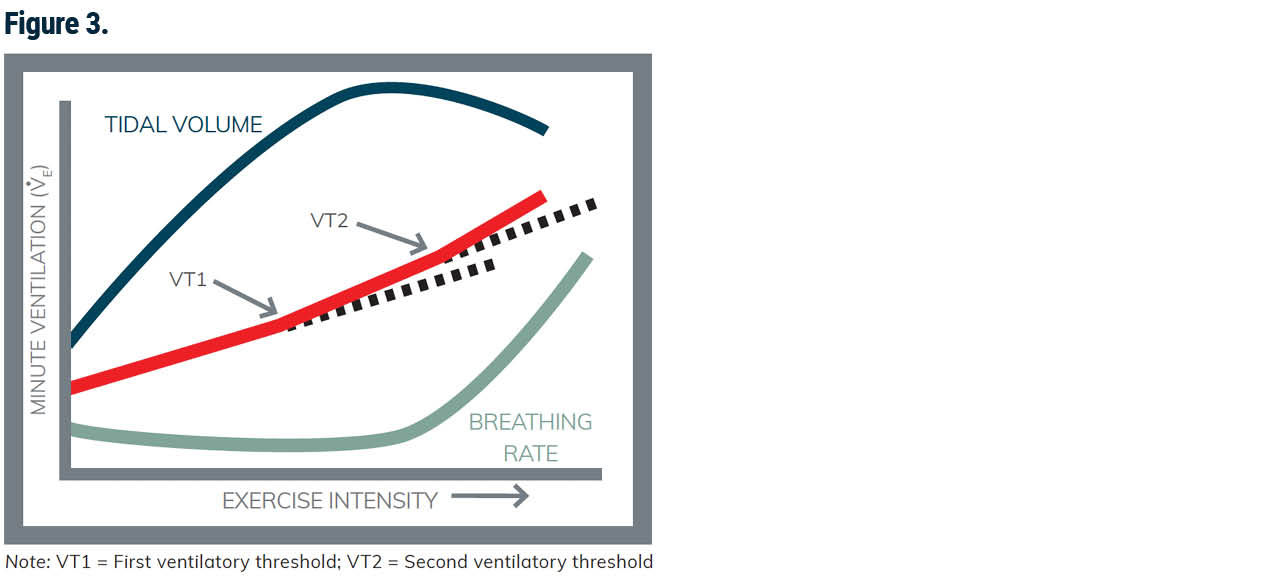

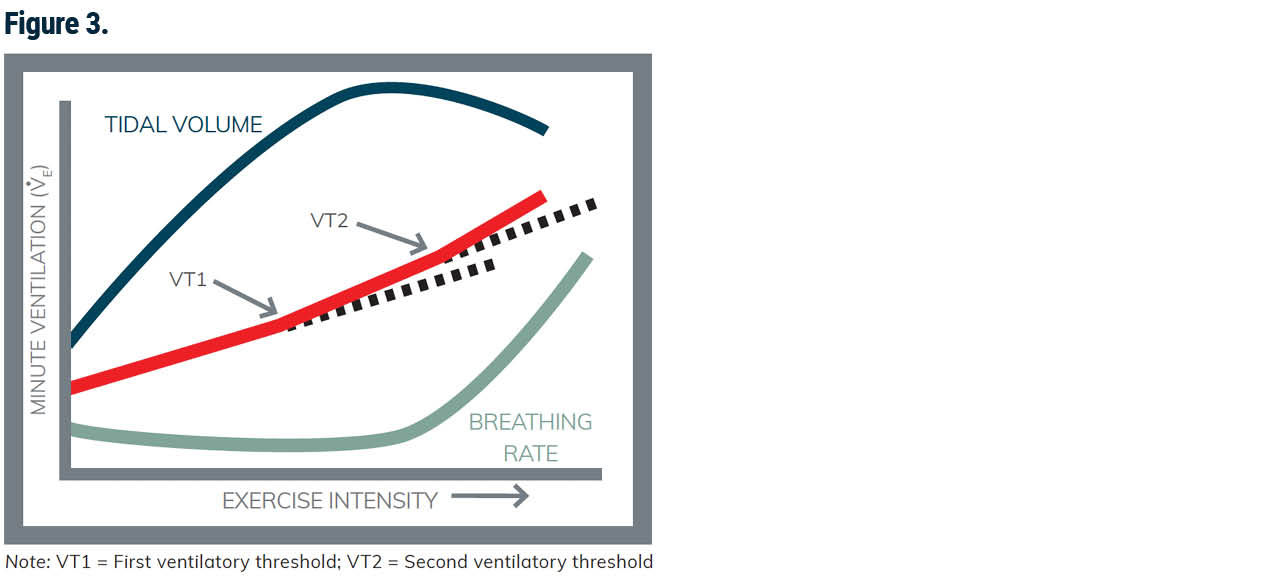

Ventilation refers to the process of moving air into and out of the lungs and is better known as breathing. During exercise, higher intensities cause an increase in breathing rates, which allows for more air to move into and out of the lungs. In other words, when exercise intensity progressively increases, so, too, does the amount of air moving into and out of the body, representing a somewhat linear relationship when exercising at submaximal levels. This initial increase in ventilation is primarily achieved by increasing tidal volume (the amount of air that moves in and out of the lungs with each breath). However, as the intensity of exercise continues to increase, there is a point at which ventilation starts to increase in a nonlinear fashion relative to intensity (Figure 3). This “crossover” point represents VT1 and corresponds with (but is not identical to) the development of acidosis in the muscles and blood and an increase lactate production. Acidosis is caused by the accumulation of proton ions that build up when adenosine triphosphate (ATP) molecules are split and leads to a decrease in pH levels creating a more acidic environment. At this point, the buildup of lactate is offset by blood buffers (compounds that neutralize acidosis in the blood and muscle fibers).

As exercise intensity further increases to near-maximal levels, the frequency of breathing becomes more pronounced and is disproportionate to the increase in oxygen uptake. This rise in breathing rate at near-maximal intensities represents a state of ventilation that is no longer directly linked to oxygen demand at the cellular level and is associated with an increase in carbon dioxide (CO2) production caused by the buffering of acid metabolites. Stated another way, initially there is a demand for more oxygen and this demand is met by increasing tidal volume, but as exercise intensity continues to increase so does the breathing rate. When exercise intensity continues to increase past the crossover point, ventilation rates begin to increase exponentially as oxygen demands outpace the oxygen-delivery system and lactate begins to accumulate in the blood. Consequently, respiratory rates increase. However, this increase in breathing rate is not driven by the need to meet the demand for oxygen but rather by the need to expire more CO2. In fact, during strenuous exercise, breathing frequency may increase from 12 to 15 breaths per minute at rest to 35 to 45 breaths per minute, while tidal volume increases from resting values of 0.4 to 1.0 L up to 3 L or greater. In well-trained individuals, VT1 is approximately the highest intensity that can be sustained for one to two hours of exercise.

The second disproportionate increase in ventilation is VT2 (see Figure 3). VT2 occurs at a point when lactate is now rapidly increasing with intensity and results in hyperventilation, even relative to the extra CO2 being produced. At this point, blowing out the CO2 is no longer adequate to buffer the acidity that is developing with progressively more intense exercise. VT2 is equivalent to an important metabolic marker called the onset of blood lactate accumulation and represents the highest intensity that can be sustained for 30 to 60 minutes in well-trained individuals. This marker represents an exponential increase in the concentration of blood lactate, indicating an exercise intensity that can no longer be sustained for long periods and the highest sustainable level of exercise intensity, which is a strong marker of exercise performance.

A person rowing a boat is a common analogy used to describe what is occurring at a cellular level within the muscles at all three training zones. Zone 1 (exercise below the talk-test threshold) can be visualized as a person rowing a boat at a comfortable pace without any issues. At zone 2 (exercise at and above the talk-test threshold but below VT2), the rowboat springs a small leak (VT1), and the boat begins to take on water (proton accumulation and lactate). However, the water is coming into the boat at such a rate that the rower can remove the water before it has a chance to significantly accumulate. For zone 3 (exercise at and above VT2), the hole in the boat becomes significantly larger (VT2) and no matter how hard the rower works to bail it out, the water begins to significantly accumulate.

How to Measure Exercise Intensity

The Talk Test

A common way to think about the talk test is to imagine two people exercising and having a conversation. One of them will eventually turn to the other and say something like, “If we are going to keep talking, we are going to have to slow down.” The talk test is based on the premise that at about the intensity of VT1, the increase in ventilation is accomplished by an increase in breathing frequency. One of the requirements of comfortable speech is to be able to control breathing frequency. Thus, at the intensity of VT1, it is no longer possible to speak comfortably.

In its most simple form, VT1 can be determined by asking a client if they can talk comfortably, or if they can talk but not sing. The great thing about this simple assessment is that it requires no equipment, and it can be done when clients are working together with you as well as when they are exercising on their own to ensure they are working at a moderate intensity.

Other options for assessing VT1 based only on a client’s ability to talk comfortably include asking clients to recite something familiar, such as saying the alphabet or “A is for apple, B is for boy, etc.,” then answer the question, “Can you speak comfortably?” If the answer is yes, the intensity is below the VT1. At the first response that is less than an unequivocal “yes,” the intensity is probably right at that of the VT1, and if the answer is “no,” the intensity is probably above VT1. When the client can no longer say more than a word or two between breaths, they are at or above VT2.

To be clear, the talk test is simply looking at a client’s ability to speak comfortably while exercising and no objective measurements such as HR are used to confirm ventilatory responses.

Submaximal Talk Test for VT1

Different from the talk test, the submaximal talk test for VT1 is best performed using heart rate telemetry for continuous monitoring. This more formal assessment requires some prep work to determine appropriate progressive increases in exercise intensity to bring about small changes in the steady-state HR (approximately 5 bpm) per stage. The basic idea of this assessment is to gradually increase the intensity of steady-state exercise while monitoring HR to observe the HR that is associated with VT1. The endpoint of the test is not a predetermined HR, but is instead based on monitoring changes in breathing rate (technically metabolic changes) that are determined by the client’s ability to recite a predetermined combination of phrases. The objectives of the test are to measure the HR response at VT1 by progressively increasing exercise intensity and achieving steady state at each stage, as well as to identify the HR where the ability to talk continuously becomes compromised. This point represents the intensity where the individual can continue to talk while breathing with minimal discomfort and reflects an associated increase in tidal volume that should not compromise breathing rate or the ability to talk.

VT2 Threshold Assessment

This assessment was developed as a field test to challenge an individual’s ability to sustain high-intensity exercise for a predetermined duration to estimate VT2. The VT2 threshold assessment requires an individual to maintain the highest intensity possible for a single bout of steady-state exercise lasting 20 minutes. Essentially, clients performing this assessment will need to maintain their highest level of intensity on a preferred piece of equipment for 20 minutes. Use of this assessment mandates high levels of conditioning in addition to experience with pacing. Consequently, VT2 testing is only recommended for well-conditioned individuals with fitness and performance goals. Like the submaximal talk test for VT1, this assessment is best performed using HR telemetry for continuous monitoring. To effectively use pacing strategies, individuals using this assessment should have experience with the selected modality they are using. To be clear, this assessment is only appropriate for individuals who are ready for performance training.

The Value of Field Tests

The benefit of all three assessments described here is that they are all field tests, which means they don’t require specialized and expensive equipment or need to be conducted within a lab setting. In its simplest form, the talk test uses the ability to talk to estimate VT1 and VT2. Talking comfortably means the client is below VT1; if they are not sure if talking is comfortable or cannot say more than a few words without taking a breath, they are at or above VT1 but below VT2; and if they definitely cannot talk, they are at or above VT2.

On the other hand, the submaximal talk test for VT1 and the VT2 threshold test both require the use of hHR monitoring and follow a specific protocol. However, these tests make it possible to estimate the specific HRs for when each ventilatory threshold is reached. For many clients, use of the talk test during exercise sessions, whether supervised or unsupervised, is a great option for monitoring intensity. For others, more specific assessments may be needed to achieve training goals. For example, some clients may need to know their HR at VT1 so they can monitor their HR during events to ensure they are working at the highest possible intensity without reaching the crossover point or VT2.

In Conclusion

"How hard should I be working?" and "How do I know if I am working hard enough?" are common questions that clients have when exercising. There are many methods for monitoring exercise intensity that can be used based on your clients’ goals, access to equipment, level of comfort and use of medication. The talk test and the use of markers for ventilatory thresholds offer a simple and reliable individualized method for monitoring intensity that aligns well with the ACE Integrated Fitness Training Model. As an exercise professional or health coach, you can work together with your clients to help them better understand how to monitor exercise intensity and determine the method that is most appropriate for them.

Expand Your Knowledge

Practical Tools for Cardiorespiratory Training

Cardiorespiratory fitness is the ultimate marker for heart health and decreased risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), yet it is often neglected by exercise professionals and perceived as training clients should do on their own time. You can greatly enhance your clients’ cardiorespiratory training using evidence-based solutions found in the ACE Integrated Fitness Training® (ACE-IFT®) Model, and you will gain practical tools to deliver individualized cardiorespiratory programs—in-person and virtually—that facilitate adherence and goal attainment.

Busy Days Call for HIIT

With lots to do on any given day, HIIT training can be a great way to maximize your time and your caloric burn. A misconception about HIIT training is that only experienced athletes should perform this type of workout. ACE Certified Pro Angel Chelik debunks that myth and provides you with the scientific data on why HIIT intervals should be incorporated into everyone’s workout routine.

by

by