Every client has a goal. The degree to which that goal is specific, measurable, realistic or process-focused varies greatly from client to client. This presents a challenge at different levels for both you as the professional and your clients. For the client, it becomes a quest to determine the “why” behind their intended goal and identifying the underlying value system that supports that goal. In contrast, as the coach, you act as the guide—not the source of all answers—whose primary role is to create a safe space for your clients to explore their why and nurture the journey of behavior change. This does, however, raise some interesting questions. Specifically, how does your scope of practice fit in? And how can you effectively and appropriately guide your clients in their goal-setting efforts without “directing” the goal itself?

The Scope of Practice

As with any client–coach or client–professional interaction or exchange, you must remain mindful of your scope of practice and operate within those guidelines. The primary role of the ACE Certified Health Coach encompasses three specific practices:

- Apply effective communication skills (such as motivational interviewing) to help clients uncover internal motivation and establish ownership in their change journey.

- Empower clients to develop and leverage their inner strengths and skills to support the changes they are attempting to adopt.

- Support clients in developing achievable and measurable goals.

The keyword in the third area of emphasis is support. Not direct or tell. You are, by training and scope, a guiding professional. This means you pour your energy into encouraging, assisting and supporting your clients in their efforts to make positive and lasting lifestyle changes. You are a partner in a client’s journey, and you respect that the client is an expert on themselves. It is your job to help clients find their own way by awakening their inner potential and self-directed learning abilities.

The Struggle

Working as a health coach is not devoid of challenges, however. Perhaps one of the most significant struggles health coaches and other helping professionals face is the inherent urge to fight the “righting reflex” or that overzealous desire to steer a client in the “right” or more appropriate direction. This reflex often takes the form of giving advice and identifying solutions for the client rather than asking them what solutions they would like to explore. Miller and Rollnick (2013) captured this best in their statement about directing the course of change. “If you are arguing for change and your client is arguing against it, you’ve got it exactly backwards.”

To Steer or Not

In addition to the scope of practice, there are ethical pillars all health and helping-related professions are built upon. These pillars include autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence and justice (Beauchamp and Childress, 2012). Autonomy means clients must think, decide and act on their own free initiative. This is where your guiding style of communication and coaching is reinforced. Setting a goal for a client and/or telling them how to rephrase a goal or what to focus on does not reflect this pillar’s values. Further, a client will not feel empowered or develop a sense of ownership if a goal is identified and set for them. You are trained to not offer advice directly and to respect that only the client knows what’s best for them. The client makes the decisions that best fit their unique reality and path forward.

Applying Goal-setting Theory to Health Coaching

Though you are unable to abide by ethical guidelines if you steer a client toward a different goal, you can apply the theories and principles of goal setting to thoughtfully aid clients in establishing clarity around an ambiguous or loosely defined goal. To do this, it is essential that you develop a solid understanding of the following:

- How goals can inspire change (goal mechanisms)

- Factors that influence behavior goals (goal moderators)

- SMART goal setting (goal characteristics) and the GROW model (a process)

Goal Mechanisms

Goals are powerful targets that encourage clients to make meaningful changes in their lives. Goals provide direction and serve as a roadmap with milestones along the path. According to Locke and Latham (2002), four primary mechanisms of goal setting drive behavioral change:

- Directed attention — Goals direct client thoughts and actions

- Mobilized effort — Goals increase a client’s effort to achieve the goal

- Persistence — Goals encourage a client to continue working toward the target behaviors

- Strategy — Goals encourage clients to be solution and action-oriented

Without a well-established goal, clients are not clear about their direction and are unlikely to establish the changes they ultimately desire.

Goal Moderators

Locke and Latham (2002) also identify five specific factors that influence how goals affect behavior and the establishment of new habits:

- Commitment — Is the client personally committed to the goal? The more commitment, the more effective the goal (this is where client autonomy is critical).

- Importance — How important is the goal to the client? Does it align with their values? The greater the importance, the greater the motivation to pursue the goal.

- Self-efficacy — The higher the client’s self-efficacy toward the target behavior, the greater persistence during times of challenge and struggle.

- Feedback — Clients who receive feedback on their progress will be more likely to continue in their pursuit of change (this is where regular check-ins from the coach and self-monitoring tools are valuable).

- Task complexity — The greater the complexity of the goal, the more strategies are required. Therefore, helping clients achieve early wins is critical.

In addition to the factors listed above, clients may also need social support and outside resources to achieve the desired change. As part of the goal exploration and clarification process, take the time to engage in an in-depth conversation about what social support looks like for your clients.

SMART and GROW

One of the best and most scientifically supported tools a professional has is the SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-bound) goal-setting approach. Not only does this tool provide you with a framework to ask deeper questions and explore a client’s "why" behind an otherwise vaguely stated goal, it guides the conversation in a way that focuses on the processes or actions a client will take versus a product or outcome they think they want to achieve. A process-oriented goal will lead to a desired outcome because change is rooted in behavior.

When using the SMART approach as your lens through which to view a client goal, consider the following scenario. A client may come to you and say, “I want to eat better.” As the professional, you may wonder what your follow-up question should be. Here, consider asking the client, “What does eating better look like to you or mean to you?” or “If you could define eating better, what do you envision as part of that definition?” By asking these types of open-ended questions, you can help the client peel back the layers of the original statement to better define their goal.

Next, you could ask your client, “What is an action you will take to eat better that fits your definition and needs?” Here, the client might respond by saying, “I will eat a salad with dinner.” This is an action the client can perform and measure if you then ask, “How often will you include this in your meal planning?” The client might say, “I believe I can do this at least three nights a week.” The client has now identified a specific action (S) that is measurable (M) in frequency, and, in all likelihood, both attainable (A) and relevant (R) to them. For the time-bound (T) aspect of SMART, you might inquire: “By what date or timeframe do you wish to fully implement this practice?” Here, the client will identify a timeframe—maybe it’s a month, maybe it’s two. Either way, you can make note of this, and check in regularly with your client to ask about their progress.

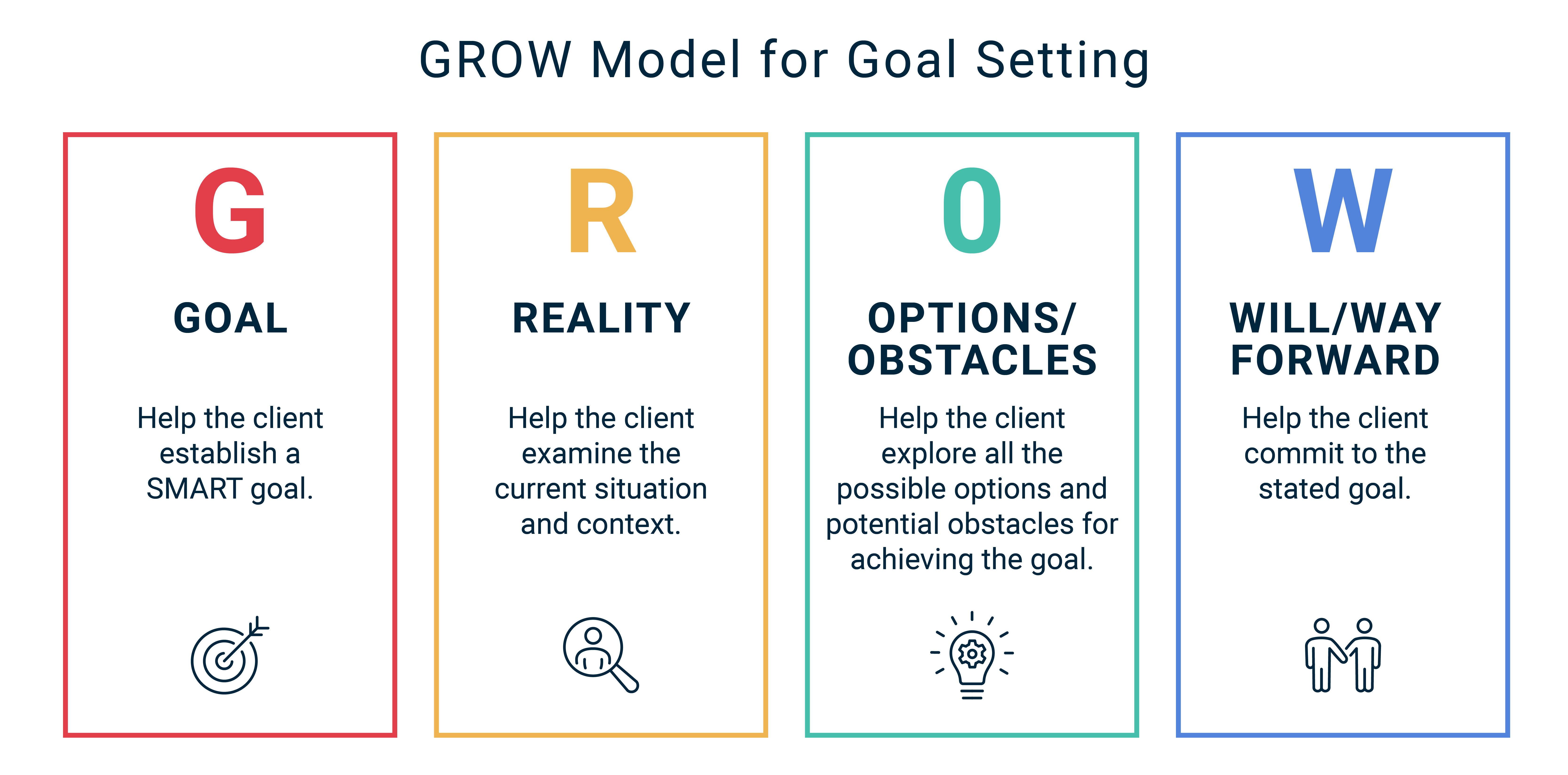

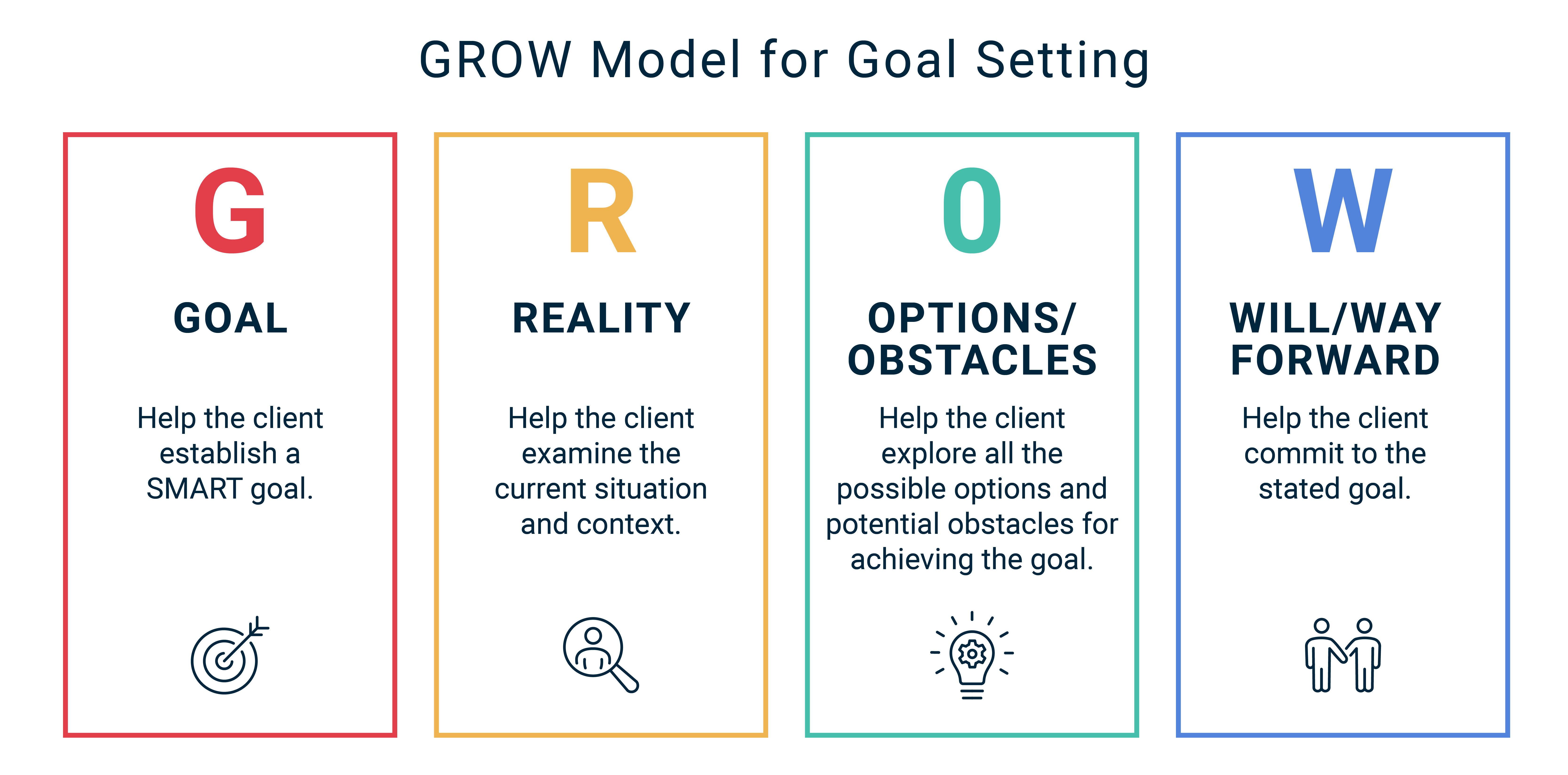

After identifying the SMART components of a goal statement, expand on this process by using the GROW model as your framework. Consider this example from my own practice with a recent client. When discussing why they were interested in seeking my services, the client said, “I want to lose weight.” This is a common goal for many clients, but while it’s a product or outcome, it does not include the actions the client needs to take to get from point A to point B. At this point, the GROW process becomes my focus. The GROW model (Figure 1) is a process of goal setting that helps you capture your client’s priorities. This approach allows you to support clients in moving from a place of goal statement to identified action steps.

When talking to my client about their weight-loss goal (G), I explored their reality (R), worked through a list of challenges or obstacles (O), and collaboratively discussed what they would do to move forward (W). Here’s what that process might look like in your work with clients:

Goal: After a client states a goal, which is likely not as specific (or process-oriented) as it could be, this is your chance to ask the client to describe why this goal is important or of value to them (to establish personal relevance and meaning). This is the start of the “why” reveal. Continue to use open-ended questions as you move through each layer. Then, ask what benefits the client perceives will be the result from achieving the goal (a deeper dig into the "why").

Reality: After gaining clarity on the why (and the client realizing the deeper meaning behind the initially nonspecific goal), ask about the context of their reality. It’s important to learn what is happening in the client’s life and what steps they may have already taken toward that goal. This helps the client identify what things in their current life may impact progress.

Options and Obstacles: Next comes the options and exploring potential obstacles. If a client has been successful with a similar goal in the past, here is the opportunity to ask what they did that resulted in success. I also like to ask clients what they feel their potential obstacles might be (lack of social support, traveling, access to a gym, etc.). Depending on what is identified, encourage clients to think about how they may work to overcome or confront those barriers. The last question—and it’s a powerful one—is to ask clients to contemplate what they might need to start doing to achieve the goal (this often uncovers the behaviors that become part of the process of change).

Will or Way Forward: The last step is about “the will,” not willpower. What will the client do to move forward? At this point, strategic questions such as “How do you plan to move forward?” “How do you think you might monitor your progress?” and “How often will you evaluate your progress?” become the focus. This is the point at which you help the client commit and outline at least two action steps they will take over the next predetermined period of days or weeks. Establish the timeline and provide the client with a summary of their plan moving forward. Bookend the conversation by asking the client how they feel about the work they did in the session and any action steps you plan to take to support their efforts.

At the link at the top of this page, ACE Certified Professionals can access a supplemental worksheet that demonstrates the GROW Model in action and outlines how to use it with clients.

Through clear, guided and open conversation, clients realize their "why" and that reason becomes the motivation to establish a change process. Using the SMART and GROW approach simultaneously, you can guide clients toward self-discovery and remain well within your scope of practice. Keep the focus on asking the right questions, not on providing answers or strategies. If you approach this type of conversation with curiosity and unconditional positive regard, your clients will naturally direct themselves.

References

American Council on Exercise (2019). The Professional’s Guide to Health & Wellness Coaching. San Diego, Calif.: American Council on Exercise

Beauchamp, T.L. and Childress, J.F. (2012). Principles of Biomedical Ethics (7th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Locke, E.A. and Latham, G.P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57, 9, 705-717

Miller, W.R. and Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Expand Your Knowledge

|

As an ACE Behavior Change Specialist, you’ll learn to build supportive client–coach relationships to help people make healthy, productive and permanent life changes.

|

|

Explore the many ways to empower your clients using their collected wearable data, allowing you to create an even more personalized and more effective workout.

|

by

by