Ask ACE: How to Help Clients Who Have Heart-related Concerns Exercise Safely

In this series, ACE experts answer your health and exercise questions. From nutrition to exercise programming, you’ll find detailed answers to many of the questions that may come up in your work with clients. If you have questions you’d like to ask our experts, please email us at Christine.Ekeroth@acefitness.org.

The Expert: John P. Porcari, PhD, is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Exercise and Sport Science at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse (UWL). He retired from UWL in 2021. John was the Program Director of the Clinical Exercise Physiology graduate program and Executive Director of the La Crosse Exercise and Health Program, the University’s on-campus Phase III cardiac rehabilitation program. He taught courses in exercise testing and prescription, cardiovascular physiology, electrocardiography and statistics. John and his colleagues conducted over 450 research projects during his 32 years at UWL, evaluating a wide variety of fitness products and exercise training techniques. He has authored or co-authored over 250 research articles and 350 abstract and is the lead author on the joint ACE/FA Davis textbook entitled Exercise Physiology. John is a Fellow of the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and a Master Fellow of the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR). He was President of AACVPR in 2003 and won the AACVPR Award of Excellence in 2010.

Q: Several of my clients are taking beta blockers, and they often get frustrated because according to their heart-rate readings on their smartwatches, they aren’t reaching their target heart rates even when they’re exercising vigorously. What advice can I give them, so they don’t want to give up on exercise altogether?

A: As hard as it may seem, if clients are on beta blockers may need to totally disregard their heart rate when they exercise. Beta blockers, as the name suggests, partially block or blunt exercise heart rates when a person is exercising. They are one of the most common drugs used by individuals who have coronary heart disease or high blood pressure; they work by limiting the increase in heart rate and blood pressure during exercise, thus reducing the workload on the heart.

As you indicate, many people guide their exercise programming by exercising at a certain percentage of their maximal heart rate. That is assuming, however, that the client knows their maximal heart rate. Ideally, they have had a maximal exercise test on either a treadmill or cycle ergometer to determine that number. While there are several prediction equations available, they all provide rough estimates and aren't very useful in practice. In reality, maximal heart rate varies greatly among people of the same age and estimated maximal heart rate is just that—a rough estimation. For a client who is taking beta blockers, unless they have had a maximal exercise test while they were on the same dosage of their beta blocker, they will have no idea what their maximal heart rate is or should be. It is impossible to predict. Beta blockers typically blunt maximal and exercise heart rates by 10 to 40 beats per minute, but the degree of reduction varies greatly based on the specific drug, the dosage and individual variation to the drug. The bottom line is, if you don’t know what someone’s maximal heart rate is, there is no way to use heart rate or percentages of maximal heart rate to guide exercise training.

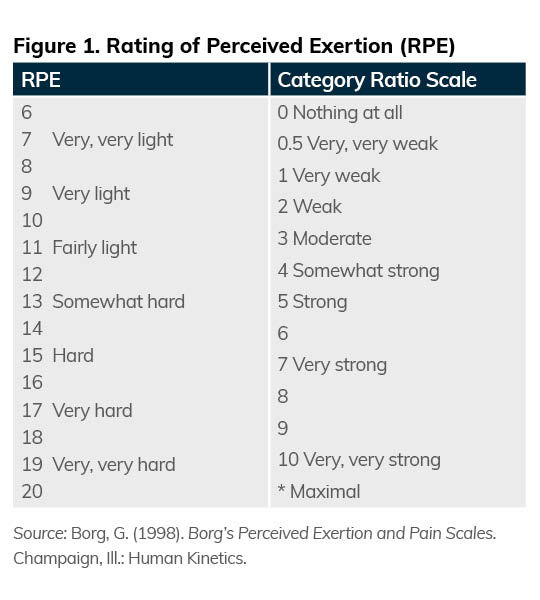

So, what is the alternative? These individuals need to use subjective methods to guide their exercise intensity. The two recommended methods use ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) or the talk test. There is extensive research to validate both methods and both correlate very closely to exercise intensities determined using specific target heart-rate ranges calculated using maximal heart rate. The Borg RPE Scale(Figure 1) uses numbers and associated verbal anchor points to guide exercise intensity. For instance, moderate-intensity exercise is usually conducted at RPE values of 12 to 13, which corresponds to approximately 64 to 76% of maximal heart rate. Vigorous exercise is usually conducted at RPE values of 14 to 17, corresponding to 77 to 95% of maximal heart rate. And RPE values of ≥18 are considered very intense exercise and correspond to heart-rate ranges of approximately ≥96% of maximal heart rate. The verbal anchor points associated with these intensities correspond subjectively to “somewhat hard,” “hard” and “very hard” exercise, respectively.

uses numbers and associated verbal anchor points to guide exercise intensity. For instance, moderate-intensity exercise is usually conducted at RPE values of 12 to 13, which corresponds to approximately 64 to 76% of maximal heart rate. Vigorous exercise is usually conducted at RPE values of 14 to 17, corresponding to 77 to 95% of maximal heart rate. And RPE values of ≥18 are considered very intense exercise and correspond to heart-rate ranges of approximately ≥96% of maximal heart rate. The verbal anchor points associated with these intensities correspond subjectively to “somewhat hard,” “hard” and “very hard” exercise, respectively.

Alternatively, there is a growing body of research literature supporting the use of the talk test to guide exercise intensity. The talk test is based on the relationship between the ability or inability to talk comfortably during exercise and someone’s lactate threshold (also called ventilatory threshold). Lactate threshold is when lactate begins to accumulate in the blood because the energy demands of exercise cannot be met solely with aerobic metabolism and must be supplemented using anaerobic processes. Steady-state aerobic training is conducted below the lactate threshold and interval training is conducted above the lactate threshold (see the next question for more on interval training). If someone can carry on a conversation during exercise, they are most assuredly below their lactate threshold. The exercise intensity at which normal speech becomes difficult (or equivocal) corresponds almost identically to an individual’s lactate threshold, and when normal speech becomes impossible, the person is clearly above lactate threshold. The equivocal stage of the talk test occurs, on average, at an intensity of approximately 80% of maximal heart rate. During moderate exercise training, most exercise is conducted at an intensity just below where a person loses the ability to carry on a normal conversation. For interval training, individuals take brief excursions above the lactate threshold (and thus can’t talk comfortably) and then recover.

While these subjective methods might not seem that precise, they are very reproducible within individuals. By trial and error, your clients can learn the association between a certain degree of perceived effort or the ability to talk, and the corresponding heart rates. Then, with this information, you can basically “reverse engineer” their exercise programming. For instance, using a smartwatch, a client may observe that when they exercise at an RPE of 12 to 13, their corresponding heart rate is 120 to 130 bpm. Together, you can then use these heart rates to guide their moderate-intensity training. If your client is engaging in interval training and you know that they lose the ability to speak comfortably at a heart rate of 135 bpm, you can use this value as the lower limit of where they conduct their higher-intensity intervals.

The good news is that if your clients on beta blockers can’t achieve the same heart rates during exercise as they did before they went on the medication, it means that the drug is doing what it is supposed to do. Fortunately, there are simple subjective alternatives to guide their exercise program, and with your help and a bit of trial and error, they can home in on a method that works for them and still achieve the same exercise-training benefits.

Q: I have a client who has numerous risk factors for developing coronary artery disease (e.g., high cholesterol, high blood pressure, elevated blood glucose, overweight) and is interested in incorporating interval training into their fitness regimen. Given the potential risks and benefits of high-intensity exercises for individuals who have heart disease or are at high risk for developing coronary disease, is it safe to introduce interval training? What should I consider to ensure this type of training is both safe and effective for my client?

A: Incorporating intervals into the fitness programs of individuals with a wide variety of health concerns has been one of the biggest breakthroughs in exercise programing in the past decade. The benefits of interval training have been shown to be equal to, or greater than, the benefits associated with traditional aerobic training and can be accomplished in a relatively shorter workout time. Interval training also adds variety to an exercise program and can break up the monotony of doing the “same old, same old” often associated with doing the same steady-state workout day after day.

First, we need to define “interval” training. Interval training is simply alternating bouts of relatively more intense exercise with less-intense recovery periods. The more intense bouts are generally conducted above the lactate threshold, while the recovery periods are conducted at an intensity that results in complete recovery before the next interval. One of the reasons interval training is such an attractive workout technique is that there are so many variables that can be manipulated. For example, the intensity of the intervals, the length of the intervals, the length of the recovery period, the number of intervals and how often interval training is performed can all be varied.

There are always risks associated with exercise and there is no way to “ensure” the absolute safety of any exercise program. However, even in individuals with known heart disease, appropriately conducted interval training has proven to be extremely safe and effective. In fact, interval training has been incorporated into most cardiac rehabilitation programs, even in patients with heart failure, with no increase in the number of untoward cardiovascular events.

One way to influence the safety of an interval-training program is to require that any client have a sound aerobic base before trying interval training. The individual should be able to perform 20 to 30 minutes of steady-state, moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, at least three days per week, for a minimum of four weeks prior to initiating higher-intensity training. They should also be aware of any abnormal signs and symptoms associated with exercise (e.g., extreme shortness of breath, palpitations, dizziness). Also, because more intense exercise is associated with higher heart rates and blood pressure, it is important to check with the client’s physician to make sure there is no reason to limit a client’s exercise intensity.

In the research literature, intervals ranging from 15 seconds to four minutes have been utilized for interval training. In fitness settings, interval durations of 20 seconds to one minute are most common, with longer durations (greater than one minute) typically reserved for competitive athletes. A general rule to keep in mind when introducing interval training is to keep the high-intensity segments relatively short (15 to 30 seconds) and the recovery periods relatively long. Over time, the goal is to lengthen the duration of the “hard” segments and reduce the length of the recovery segments. A sample program might involve having the client complete a 10- to 15-minute warm-up at their normal training pace. Then, you might add in 30 seconds of relatively higher-intensity exercise, followed by a two-minute recovery period just below where they normally perform their aerobic training, which should ensure a complete recovery. This pattern could initially be repeated three to five times, followed by a five-minute cool-down. Over time, the client could gradually increase the duration of the more intense segments (up to one minute) and reduce the length of the recovery period (down to one minute), until there is a one-to-one work-to-recovery ratio. You could also increase the number of intervals they perform, if appropriate. In practice, you may find that clients will have varying preferences as to which variables are manipulated, and the possibilities are endless in terms of the varying combinations you can devise. Additionally, keep in mind that interval training does not need to be conducted during every workout. One to two interval sessions per week is generally recommended.

Q: We have a new client at our club who recently completed cardiac rehabilitation at a local hospital after experiencing a heart attack approximately four months ago. Are there any specific precautions they should take when starting back to exercise? Is it safe for them to lift heavy weights?

A: First, let’s be clear that resistance training should be an integral component of any fitness program, regardless of the health status of the individual. In everyday life, we are all required to lift and carry things and walk up stairs (for instance), all of which require a certain degree of muscular strength. Increasing muscular strength makes performing everyday activities such as these perceptually easier, and individuals who have experienced a health setback are no exception.

When an individual returns to exercise following a cardiac event such as a heart attack, there are a number of factors that should be considered, such as the age of the individual, any additional health concerns they may have, and what were they doing from an exercise perspective prior to their heart attack. It is also imperative to try and get the records of the individual and see what they were doing in cardiac rehabilitation. If they are joining the club immediately after completing cardiac rehabilitation, they should have some idea of what their capabilities are from an aerobic exercise intensity point of view. They should also be alert to any abnormal signs and symptoms that might occur while they are exercising. If there was not much of a delay between the completion of cardiac rehabilitation and joining the club, the individual may be able to pick up where they left off for aerobic exercise.

In terms of resistance training, most cardiac rehabilitation programs now include resistance training as part of a well-rounded program. However, the resistance training is generally low-intensity and involves resistance bands and light dumbbells. In a club setting, it is generally considered safe for clients with known heart disease (e.g., heart attack, stent, bypass surgery) to perform resistance training. If the individual has not done any resistance training prior to their heart attack or while in cardiac rehabilitation, it is prudent to have them start with light dumbbells, focusing on range of motion, proper technique and breathing. The most important thing to avoid in individuals with cardiac disease is the large increase in blood pressure associated with the Valsalva maneuver (i.e., holding their breath while exerting force). Once they feel more comfortable doing some resistance training, it is generally considered safe for them to do more “traditional” weight training using machines and some free weights.

Guidelines from all the major fitness organizations conclude that it is safe for patients with cardiovascular disease to perform moderate-intensity resistance training. This exercise intensity ranges from 40 to 60% of one-repetition maximum (1-RM) or uses a weight that the individual can lift 10 to 15 times with a moderate degree of subjective effort (RPE 11 to 13). This amount of weight seems to strike a good balance between building muscular strength and endurance, while minimizing the spike in blood pressure typically associated with resistance training. It should be noted that studies investigating resistance training in cardiac patients have not shown an increase in adverse events if the weight is moderate and the person avoids the Valsalva maneuver. In fact, participants in cardiac rehabilitation have fewer cardiovascular issues during resistance training compared to aerobic training. Because there is a slightly higher diastolic blood pressure during resistance training compared to aerobic training, coronary artery blood flow is enhanced, resulting in better cardiac function.

In terms of lifting “heavy” weights, there are several factors to consider. Heavy weights are typically defined as being greater than 80% of an individual’s 1-RM. The main factor to consider is what the individual was doing from a resistance training point of view prior to their heart attack. Unfortunately, we are seeing younger and younger men and women suffer from cardiovascular disease, which means both clubs and health and exercise professionals are increasingly likely to work with individuals with these concerns. Some of these individuals were lifting “heavy” weights prior to their heart attack or may need to return to jobs that require heavy lifting or exertion. The literature indicates that individuals who were lifting heavy weights prior to their heart attack can resume the same level of activity as before their heart attack if they progress back slowly and are cognizant of their breathing. When individuals are lifting heavier weights, they usually do fewer repetitions. With resistance training, blood pressure goes up in a stair-step fashion with an increase in the number of repetitions. Because the individual is performing fewer repetitions, the fact that they are lifting a heavier weight is balanced out by the lower number of repetitions and shorter exercise duration.

Expand Your Knowledge

Practical Tools for Cardiorespiratory Training

Cardiorespiratory fitness is the ultimate marker for heart health and decreased risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), yet it is often neglected by exercise professionals and perceived as training clients should do on their own time. You can greatly enhance your clients’ cardiorespiratory training using evidence-based solutions found in the ACE Integrated Fitness Training® (ACE-IFT®) Model. In this course, you will gain practical tools to deliver individualized cardiorespiratory programs—in-person and virtually—that facilitate adherence and goal attainment.