When starting a career in the fitness industry, it’s not unusual for new health and fitness professionals to take every opportunity to earn additional income, which usually means seeing clients both early in the morning and later in the evening, in addition to teaching multiple fitness classes in a day. This type of overscheduling is a component of “trainer burnout,” but one that can be remedied with time management and scheduling.

There is, however, another type of burnout that too many health and fitness professionals—newbies and veterans alike—are susceptible to: the physiological overtraining caused by teaching too many fitness classes or participating in too many of the workouts you’re leading without taking the appropriate time for rest and recovery between workouts. This type of overtraining can lead to a number of potential health problems that can negatively impact your overall quality of life.

Are you reading this and nodding your head? Do you worry you’re headed for burnout, but aren’t quite sure how to ease up on your training load or workouts? Read on to learn how to determine if you’re overtraining and, importantly, how to integrate adequate rest and recovery time into a full schedule of training clients and teaching classes.

Overtraining Syndrome

It is a great feeling to lead the workouts that help others improve their lives. However, physically participating in every class you teach, especially high-intensity interval training (HIIT) formats, can be physiologically demanding and lead to overtraining. Obviously, exercise is good for us and can provide numerous health benefits, but exercise is also physical stress applied to the body and too much exercise can lead to a number of health problems that can be classified as overtraining syndrome (OTS). Hausswirth and Mjika (2013) describe OTS as “prolonged, excessive training combined with other stressors and insufficient recovery time, resulting in decreased performance and chronic maladaptations.” Given this definition, it is not surprising that many instructors and trainers are at risk of physiological overtraining, which can easily lead to burnout and general job dissatisfaction.

Technically speaking, OTS is related to performance decrements in a specific sport and, because health and fitness professionals don’t have quantitative, job-related performance metrics like running a specific distance in a certain time or lifting a predetermined amount of weight, it can be a challenge to identify whether an individual is actually experiencing OTS-related fatigue. OTS is recognized as a combination of excessive exercise and too-little rest or recovery between exercise sessions. This makes early recognition of OTS in health and fitness professionals virtually impossible because the only certain sign of this condition is a decrease in performance during competition or training. Furthermore, a definitive diagnosis of OTS requires ruling out an organic disease, iron deficiency with anemia or infectious diseases (Hausswirth and Mjika, 2013). While this criteria makes it difficult to determine whether OTS is the specific cause of burnout or a health issue, combining scientific evidence with anecdotal experience certainly seems to suggest that OTS may play an important role in trainer burnout. Fortunately, this type of burnout can generally be addressed with a few simple changes to work schedule or, most importantly, teaching style.

Case Study 1: The Overtrained Overachiever

Angela Leigh is the program director for Pure Yoga in New York City and has been a group fitness instructor for more than a decade. When she was a full-time fitness instructor and presenter in Los Angeles, she took pride in doing every one of the group classes she taught. Leigh pushed her classes to extreme levels of intensity because she wanted to be known as the hardest instructor in her area. She would teach her normal group fitness schedule, sub classes for other instructors, and then travel to teach workshops or conference sessions on the weekends. In addition to her workload of fitness classes, she was also working with a trainer and doing her own workouts six days a week. Then she started getting sick.

“Colds, sore throats, fevers, the flu—it seemed like I was continuously getting sick,” says Leigh. “When I finally had blood work done, the doctors told me that my white blood cell count was so low they thought I had mononucleosis. They explained that my immune system was so overwhelmed that it did not have the ability to fight any disease. When I looked at my schedule, I realized that I was overexercising, undereating and not paying any attention to the amount of sleep I was getting—all of which led to being overtrained.”

The symptoms Leigh experienced were significant and, in some cases, debilitating. “Even though I was exercising and limiting my caloric intake, I experienced weight gain, I couldn’t sleep at night and, according to the doctors, my immune system was trashed,” she explains. “My body was completely breaking down. In short, I felt like a stranger in my own skin.”

Leigh received her diagnosis in 2015 and still feels that she is not 100% recovered and back to her normal self.

“As I started to focus on getting better, I had to back off exercise, make a specific effort to eat a balanced diet, make time for more sleep and learn how to coach my classes instead of simply leading them through a workout,” describes Leigh. “Now when I teach classes, I focus on coaching my participants to perform their best as opposed to trying to kick their butts with a super-intense workout.”

“As I started to focus on getting better, I had to back off exercise, make a specific effort to eat a balanced diet, make time for more sleep and learn how to coach my classes instead of simply leading them through a workout,” describes Leigh. “Now when I teach classes, I focus on coaching my participants to perform their best as opposed to trying to kick their butts with a super-intense workout.”

One probable cause of OTS is an imbalance between the intensity and volume of exercise and an inadequate amount post-exercise rest, refueling or recovery. Metabolic stress is one criterion for identifying OTS because it can overwhelm numerous physiological systems, including the muscular and the endocrine systems, which are responsible for producing the chemicals that determine cellular function.

During exercise, metabolic stress occurs when a muscle has to produce the energy necessary to contract and perform physical work. When a muscle works to a point of momentary fatigue, that’s a signal that an appropriate amount of metabolic stress has been applied and the involved muscle has depleted its supply of glycogen. One of the most important functions of the post-exercise recovery process is an adequate intake of the macronutrients—protein, carbohydrate and fat—which are used to replace spent energy, repair damaged tissue and support essential physiological functions. As Leigh experienced, combining too much exercise with a reduction in caloric intake can lead to significant health consequences.

Case Study 2: The Rhabdomyolysis Wake-up Call

Desiree,* an ACE Certified Group Fitness Instructor in her early thirties, taught group fitness classes—at least two classes a day on most days of the week—in addition to working a full-time job outside the fitness industry. She also taught workshops for other group fitness instructors and would sub classes whenever she could. This led to teaching group fitness classes for weeks in a row with little-to-no time off—a schedule that ended up putting her in the hospital with rhabdomyolysis.

Rhabdomyolysis, which is a breakdown of creatine in the blood stream that causes the blood to become toxic, can be fatal if not treated in time. It had been extremely hot and Desiree had been teaching more than her normal workload, participating in the classes she taught and pushing her participants to exercise at high levels of intensity. When Desiree could barely walk after her regular Monday night step class, she realized something was wrong and went to the hospital. Doctors immediately diagnosed the issue and determined a course of treatment that enabled her to recover in a relatively short amount of time with no lasting consequences.

Rhabdomyolysis, which is a breakdown of creatine in the blood stream that causes the blood to become toxic, can be fatal if not treated in time. It had been extremely hot and Desiree had been teaching more than her normal workload, participating in the classes she taught and pushing her participants to exercise at high levels of intensity. When Desiree could barely walk after her regular Monday night step class, she realized something was wrong and went to the hospital. Doctors immediately diagnosed the issue and determined a course of treatment that enabled her to recover in a relatively short amount of time with no lasting consequences.

Building lean muscle mass and improving aesthetic appearance is often perceived as an essential requisite for working in the industry, but too much exercise can reduce muscle growth. During the post-exercise recovery process, protein, along with the hormones testosterone, human growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1, repairs muscle cells damaged by the mechanical stresses of exercise. If the volume of exercise is too high and the length of time between workouts is too short, the body may begin to use protein as a source of fuel (the hormone cortisol can help convert protein to ATP during a process called gluconeogenesis), which limits the amount available to repair muscle tissue damaged during the workout (Hackney, 2006).

Case Study 3: The Thyroid Gland That Wouldn’t Quit

Amanda Mercer is an ACE Certified Personal Trainer and the owner of the THRIVEfitt Studio in Marietta, Ohio. In 2015, she experienced a thyroid nodule that grew to three times its original size and restricted oxygen intake into her body. She is convinced that her overtraining as a group fitness instructor resulted in the hyperthyroid condition.

“I believe that high-intensity exercise combined with inadequate sleep and teaching all the classes I could possibly teach in a week while only fueling with granola bars and protein shakes was not sustainable and could have killed me if I had kept following that path,” says Mercer. “Now I monitor how healthy my daily habits really are—if I am too busy to eat real food or get quality sleep, then I need to adjust my schedule.”

Mercer says that the biggest sign that she needs to make a change is when teaching starts to feel more like a chore than a pleasure. “When I start to consistently dread classes, I need to change it up,” Mercer explains. “Sometimes it’s as simple as a new format—other times I need to simply take a couple of days off. I’m working much harder to listen to my body and give it what it needs.” This is good advice for all of us, whether or not we are at risk of overtraining.

Mercer has also become much more adept at leading her classes without having to participate in the full workout. “When I teach, I use students in class to demonstrate an exercise, which helps create engagement in a circuit or boot-camp style format,” she says. “I’ve become a great actor—I don’t always do the classes I teach. [For example,] during cycling classes, I get off the bike and walk around as I coach the riders, rather than simply push them to work harder.”

The perception is that fitness professionals are in extremely good shape and have the ability to exercise all of the time. However, while regular exercise is good for you, these stories demonstrate that too much exercise or exercising at a high intensity too often, and without the proper recovery could be the catalyst for the development of significant health issues or, in certain rare cases, even be fatal. The key to minimizing your risk as a health and fitness professional is to identify specific strategies that allow you to continue doing what you love, while also keeping your body—arguably your most valued asset—in optimal health.

Identify Recovery Strategies that Work for You

Researchers have identified three different types of recovery (Bishop, Jones and Woods, 2008):

- Immediate—the moment between each individual repetition in a set

- Short-term—the time frame immediately after completing a set of a particular exercise

- Long-term—the length of time between workouts

For professionals and clients alike, specific recovery strategies are necessary to help mitigate the effects of exercise and to promote the optimal repair of tissue and the replenishment of energy expended during a workout. In the same way you design specific exercise programs for your individual clients, recovery programs should also be tailored to meet the needs of specific work and exercise schedules. It is important to note that recovery doesn’t just mean rest time and can include a wide range of approaches and tactics. For example, following a high-intensity training day with a low-intensity workout like using myofascial release to reduce muscle tension or simply walking can actually help the body recover more quickly from the challenging workout the day before.

Periodization, which is the process of systematically planning short- and long-term training programs by adjusting the intensity of exercise and allowing for appropriate long-term recovery between workouts, is a great way to avoid overtraining. When planning workouts, the primary purpose of periodization is to schedule an appropriate application of exercise stimulus, manage fatigue and avoid overtraining (Hausswirth and Mjika, 2013). Although periodization was originally developed for use with athletes who have a specific competition schedule, it’s an effective strategy for instructors with an established class schedule. For example, your hardest workouts can happen on days when you don’t teach any classes, or you can perform a lower-intensity, recovery-based workout on days when you have to teach one or more classes.

The Type of Classes You Teach Matters

In recent years, group fitness programming has focused on high-volume, high-intensity formats. Variable, high-intensity strength- and power-training programs, demanding indoor-cycling workouts and excessive exposure to elevated temperatures during heated yoga all apply extreme levels of physiological stress to the body. It’s important to remember that these classes are for the participants to get a workout, NOT the instructor.

In recent years, group fitness programming has focused on high-volume, high-intensity formats. Variable, high-intensity strength- and power-training programs, demanding indoor-cycling workouts and excessive exposure to elevated temperatures during heated yoga all apply extreme levels of physiological stress to the body. It’s important to remember that these classes are for the participants to get a workout, NOT the instructor.

The body adapts to an exercise stimulus during the recovery period between workouts and there are a number of important things that can speed up the repair of damaged tissue and promote muscle growth. The proper care of your muscle and connective tissue, the quality and quantity of sleep and, believe it or not, the types of clothes you wear all can promote the post-workout recovery necessary to help you to maximize the results from your time spent sweating.

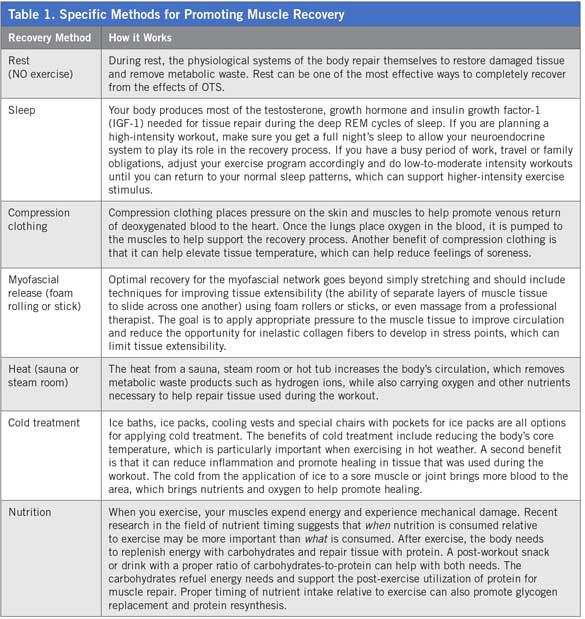

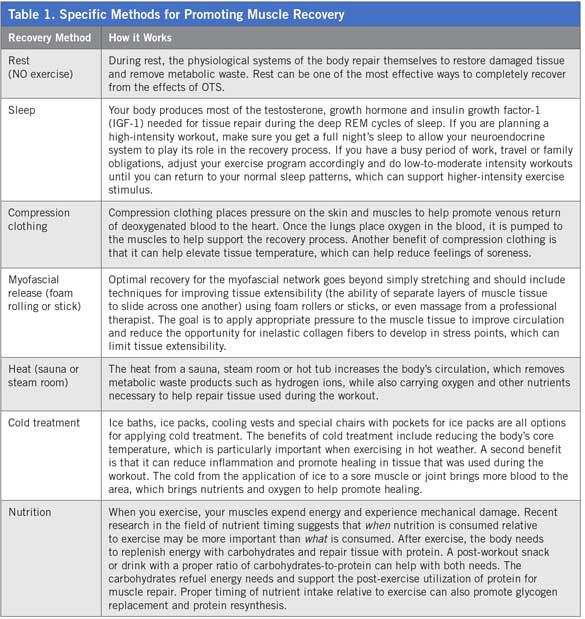

As Bishop and colleagues (2008) astutely pointed out, “Overtraining is under-recovery.” As a health and fitness professional, you are always giving clients advice on how to make healthier choices. Don’t forget that it’s important for you to also slow down, model healthy behaviors and demonstrate successful approaches to recovery, such as those outlined in Table 1.

COACH the Workout Instead of Doing the Workout

Yes, as a group fitness instructor it is necessary to be in good shape and have the ability to do the workout that you are teaching, but one of the most effective recovery strategies for fitness professionals is to stop actually doing the classes you teach and instead coach the participants through the workout.

“I think its important for fitness professionals to realize that they are role models and that daily, high-intensity or long-duration training held up to participants as some example of what they too should be doing is an outdated and, frankly, egocentric model of being an instructor,” says Irene Lewis-McCormick, M.S., a fitness educator and head trainer at Orange Theory Fitness in Ames, Iowa. “It is important to lead by example. If an instructor is constantly exercising both during and after group fitness classes, he or she is not acting as a good role model for clients and class participants. Coaching classes instead of doing them and talking about the benefits of post-exercise recovery are opportunities to educate members on proper self care as it relates to exercise.”

For example, if you’re teaching an indoor cycling class off the bike, let participants know that it is a rest day for you and that, as a coach or instructor, you don’t need to do the work to ensure that everyone in the class meets his or her individual goals. Modeling healthy behaviors can help ensure that the people you influence understand that exercise is more than just what happens in the gym.

“At Equinox, we are aware of the dangers of overtraining for our instructors, which is one reason why we place an emphasis on our instructors' ability to coach a class through a workout,” says Amy Dixon, senior creative manage for group fitness at Equinox and the 2015 IDEA Group Fitness Instructor of the Year. “To help foster this approach, we have designed a number of signature group fitness class formats that allow our instructors to connect with our members as they coach them through a class, as opposed to physically leading the class while the members follow.”

For Leigh, learning how to coach participants through a workout instead of leading them through it by example allows her to avoid a repeat of the health issues that have only recently begun to heal.

“As an instructor, I used to challenge my classes to work harder and push them to exercise at the highest intensity possible while I was doing the class along with them,” Leigh admits. “As I began the recovery process, I starting changing the way I taught so that I didn’t do every single class. I also changed the language I use and how I cue, which has had a powerful impact on my classes.”

Today, instead of challenging her participants to work harder, Leigh coaches them to work at a specific rate of effort or to focus on the movement they’re performing. “I want people to walk out of class feeling successful with a sense of accomplishment instead of leaving feeling wasted and completely thrashed,” she says.

Learning From Others

Leigh makes a compelling argument for why health and fitness professionals need to embrace the concept of recovery, for themselves as well as their clients: “As health and fitness professionals, we work in the service industry—we are here to serve others, not ourselves. “But if we don’t take care of ourselves, we won’t be able to provide the service that our clients and class participants deserve.”

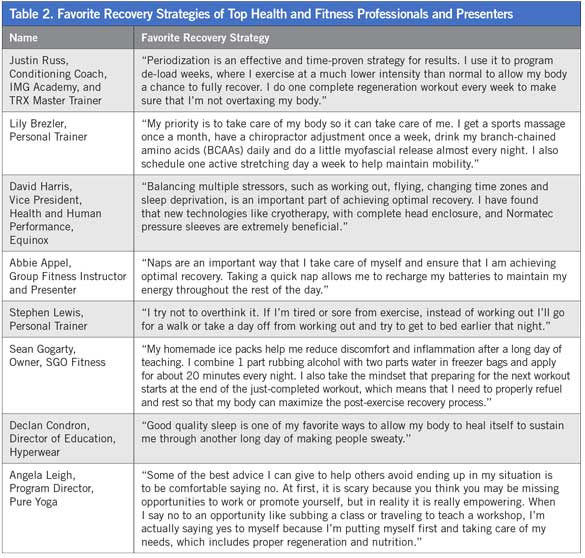

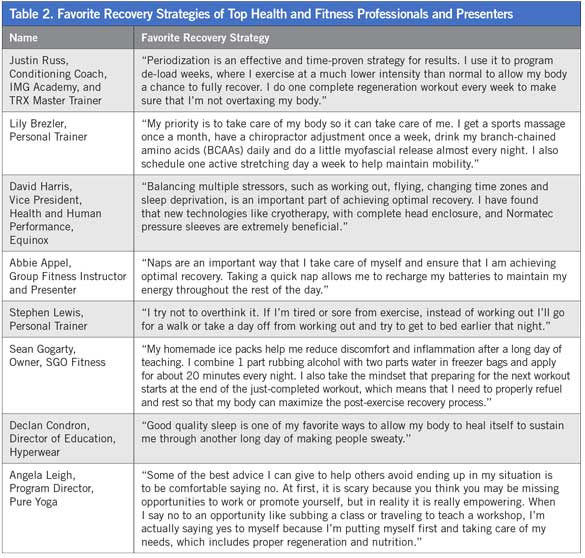

There are many recovery strategies to choose from, and some are more effective than others. In Table 2, a number of veteran fitness professionals share their strategies for maximizing recovery, managing their schedules to avoid OTS, and making an effort to spend time away from the gym. Take a look at their advice and choose the strategies that are most appropriate to your situation.

Regardless of what your teaching and training schedule may look like, giving your body the time to adequately recover from the rigors of this profession is a decision only you can make for yourself. Given that your body is arguably your most valuable asset as a health and fitness professional, choose wisely.

Further Your Knowledge

To learn more about the recovery process and how it replenishes the body’s ability to do physical activities, check out this report on The Science of Post-Exercise Recovery by the American Council on Exercise.

References

Bishop, P., Jones, E. and Woods, K. (2008). Recovery from training: A brief review. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22, 3, 1015-1024.

Hackney, A. (2006). Stress and neuroendocrine system: The role of exercise as a stressor and modifier of stress. Expert Reviews of Endocrine Metabolism, 1, 6, 783-792.

Hausswirth, C. and Mujika, I., (2013). Recovery for Performance in Sport. Champaign, Ill.: Human Kinetics.

by

by

“As I started to focus on getting better, I had to back off exercise, make a specific effort to eat a balanced diet, make time for more sleep and learn how to coach my classes instead of simply leading them through a workout,” describes Leigh. “Now when I teach classes, I focus on coaching my participants to perform their best as opposed to trying to kick their butts with a super-intense workout.”

“As I started to focus on getting better, I had to back off exercise, make a specific effort to eat a balanced diet, make time for more sleep and learn how to coach my classes instead of simply leading them through a workout,” describes Leigh. “Now when I teach classes, I focus on coaching my participants to perform their best as opposed to trying to kick their butts with a super-intense workout.”

In recent years, group fitness programming has focused on high-volume, high-intensity formats. Variable, high-intensity strength- and power-training programs, demanding indoor-cycling workouts and excessive exposure to elevated temperatures during heated yoga all apply extreme levels of physiological stress to the body. It’s important to remember that these classes are for the participants to get a workout, NOT the instructor.

In recent years, group fitness programming has focused on high-volume, high-intensity formats. Variable, high-intensity strength- and power-training programs, demanding indoor-cycling workouts and excessive exposure to elevated temperatures during heated yoga all apply extreme levels of physiological stress to the body. It’s important to remember that these classes are for the participants to get a workout, NOT the instructor.