For people struggling with long COVID, having the illness can sometimes feel like the collective experience the world faced with the pandemic itself, filtered down to the personal level. A persistent lack of clarity about who gets it and why. Questions of how long it’s going to last and what it will take to get “back to normal.” Confusing and inconsistent symptoms. And the psychological difficulty and often overwhelming stress that come with facing so much uncertainty.

There is a common misperception that long COVID involves an extension of the flu-like symptoms typically associated with COVID-19. Others may believe it’s simply a later flare-up that causes a person to feel ill for a second time. The truth, however, is that long COVID is a much more profound and troubling condition than most of us realize.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), long COVID involves a “wide range of new, returning or ongoing health problems that people experience after first being infected with the virus that causes COVID-19” and “can last weeks, months or years.”

Unusual Amounts of Fatigue

As you can see from this description, there is no “typical” case of long COVID—it can have any number of symptoms for any length of time. All of this hit close to home for the ACE family when Cedric X. Bryant, PhD, FACSM, ACE’s President and Chief Science Officer, began his own fight against long COVID earlier this year. The following is a quick rundown of his experience, along with some insights he wanted to share with ACE Certified Professionals who may have clients returning to exercise after having long COVID.

Dr. Bryant was infected with the omicron variant during the first week of January 2022 and his only discernible symptom was mild fatigue for 24 to 36 hours or so. He then felt perfectly fine for about four or five weeks, at which point he began to feel diffuse joint pain and stiffness and unusual amounts of fatigue.

The symptoms persisted, so Dr. Bryant reached out to his physician, who suspected that he was going through a post-COVID inflammatory episode and did labs to measure his C-reactive protein level, which is a marker of general inflammation and often used to determine a person’s risk of cardiovascular disease. Dr. Bryant’s C-reactive protein level was shockingly elevated, at more than 40 times above normal levels.

Given this result, Dr. Bryant was referred to a rheumatologist to rule out various types of arthritis and all test results were clearly negative, at which point Dr. Bryant was diagnosed with long COVID.

Over time, the pain and stiffness subsided, but the fatigue and general malaise persisted. “I love to be active,” he says, “so I thought, well, maybe if I do some light exercise—and I really mean light in terms of being well below the talk-test threshold—I might start to feel more energetic, but the exact reverse happened.” After 15 minutes of super-low intensity cycling on a recumbent bike, Dr. Bryant says he was “wiped out.”

It took another six weeks before he was able to tolerate moderate levels of activity. Then, in mid-May, Dr. Bryant, a self-described “golf addict,” decided to play 18 holes. He purposely chose a relatively flat course to avoid overdoing it. The next day, he says, “I felt like I’d run a marathon.” Then, he began to have a relapse of malaise associated with both mental and physical exertion.

This is another way in which long COVID is reminiscent of the pandemic itself, as a false sense of normalcy sometimes appears and causes people to modify their behavior in an effort to get back to the way things were before. Remember the lifting then reinstituting of mask mandates and the opening then reclosing of gyms and restaurants? Dr. Bryant felt himself feeling better and loosened the restrictions on his physical and mental exertion levels, only to have to go back into shutdown mode.

He also realized that he had to become more judicious with the use of his time with any tasks that required cognitive abilities, particularly if they included screen time. For example, he limited his reading and editing to 60 to 90 minutes before he’d need to take a nap. For context, when healthy, Dr. Bryant often walks on the treadmill for up to four hours at a time while editing manuscripts, as he likes to couple his physical and mental activities to maximize his time. With long COVID, either form of activity alone prompted severe fatigue.

To Learn More…

If you or any of your clients are battling long COVID, Dr. Peabody suggests the following resources to learn more about the condition:

The Dangers of Pushing Through Fatigue

One of the hallmarks of long COVID is post-exertional malaise, and this proved to be the centerpiece of Dr. Bryant’s experience. After his body’s response to his golf outing, his physician recommended that he learn to find a “new normal” in terms of his physical and mental exertion, and that he avoid pushing himself anywhere close to his limits, as the overexertion and resulting malaise would be detrimental to his overall recovery.

Dr. Stephanie Peabody, PsyD, HSPP, neuropsychologist and the Founder and Executive Director of the Brain Health Initiative, who herself has had a prolonged battle with long COVID dating back to early 2020, says that we must educate everyone who is touching the lives of people who are impacted that trying to push through fatigue or malaise can cause injury—and even permanent injury—to those with long COVID. The Brain Health Initiative is dedicated to collecting data and raising awareness that the physiological and cognitive symptoms that people experience are real. Health coaches and exercise professionals can play a vital role in increasing the public’s awareness of the severity of this condition.

This is where the psychological battle with long COVID comes in, as patients are forced to balance the desire to get back to normal with the need to recover. Dr. Bryant says his post-golf fatigue was the last wake-up call he needed to do everything required to recover. That meant being patient and going against his natural instincts, which tell him that movement and exercise are essential and normal parts of his daily routine.

The malaise caused Dr. Bryant to spend a lot of time in his recliner resting and taking naps, so much so that he realized that he needed to keep his core strong to prevent low-back pain. So, he began doing a few minutes of stretching each day, along with some planks—and that was the extent of his physical activity efforts while he recovered. On the cognitive side, he scheduled breaks between on-screen meetings and between tasks that required high levels of mental focus.

I’m happy to report that since mid-June—after a nearly five-month journey—Dr. Bryant feels like himself again and has been able to consistently exercise at a level adequate to meet the Physical Activity Guidelines (four or five moderate-intensity cardio workouts each week, along with two rounds of light resistance training) without feeling any undue fatigue afterward.

Research into Long COVID

The research into the symptoms and long-term effects of long COVID is ongoing and we may not know the true cost of the COVID-19 pandemic for many years. That said, researchers have already painted a pretty dramatic portrait. One of the most shocking things about long COVID—and perhaps the reason that diagnosis and care are so difficult—is the broad range of sometimes confounding symptoms. On its “Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions” page, the CDC actually has a section entitled “Symptoms that are hard to explain and manage.”

The Patient-Led Research Collaborative (PLRC) is a group of long COVID patients who are also researchers and whose work has informed most long COVID guidelines, including those from the CDC and the World Health Organization. Their initial research included a survey of 3,762 people and has since grown to include approximately 8,000 patients from 80 countries.

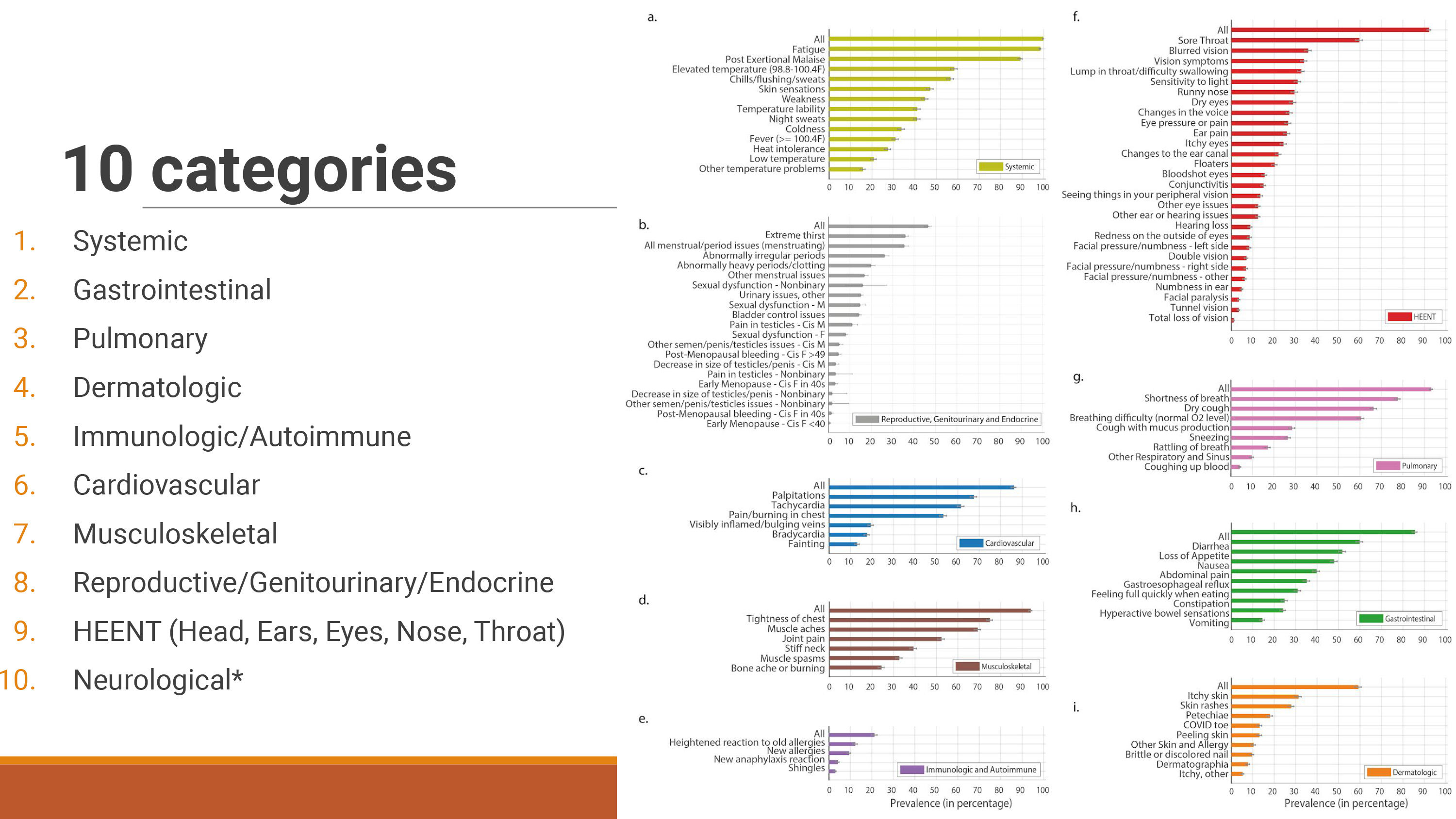

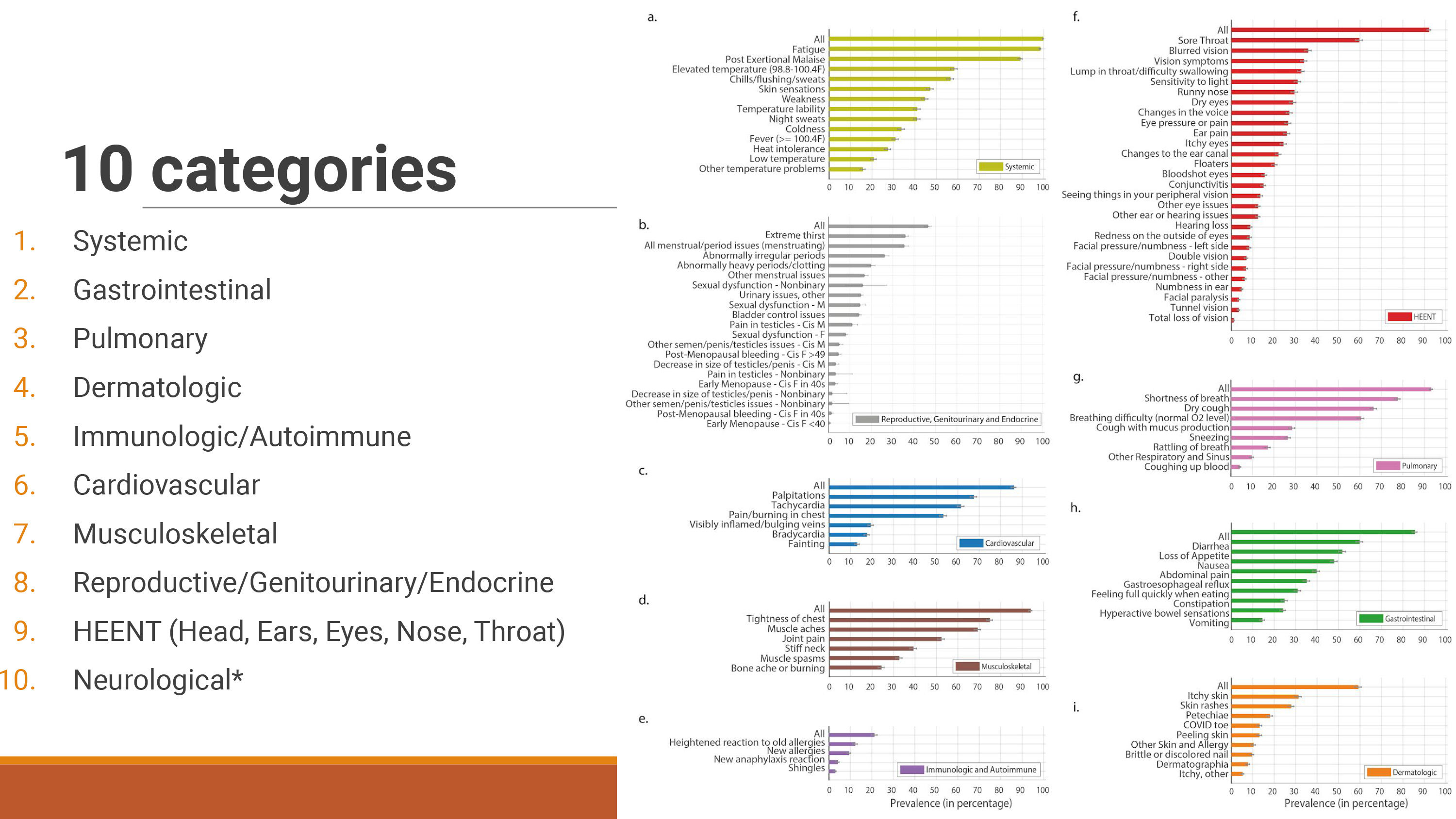

The PLRC asks participants to complete a 500-question survey that covers symptoms, treatments, medical care and stigma, impact on life and pre-existing conditions, along with a number of pieces of qualitative information. According to their findings, the average long COVID patient experiences 56 symptoms over an average of 91 days, and more than 200 symptoms have been identified through their surveys. These symptoms fall into 10 categories, as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. 10 Categories of Long COVID symptoms. Used with permission from Hannah Davis’s presentation “Long COVID & the Brain” at Drs. Stephanie Peabody and Shelley Carson’s Harvard course Psych #1612, The Science and Application of Brain Health and Performance.

The two most common symptoms are fatigue and post-exertional malaise, which are obviously of concern to the work of exercise professionals. “The main point,” says Hannah Davis, who is the cofounder of the PLRC and has a background in data analysis and machine learning, “is that long COVID patients with post-exertional malaise can’t exercise—it can worsen symptoms and cause them to become bedbound. It is counterintuitive because exercise helps so many illnesses, but it worsens symptoms for many people with post-viral conditions.”

In fact, exercise worsens symptoms in 75% of long COVID patients, while improving them for only 1%. Other research has shown that long COVID patients experience exercise intolerance and adverse effects from exercise.

For these reasons, Davis goes on to say that, “Any exercise program needs to rule out post-exertional malaise before undertaking any exercise protocol.” This, she says, is the key takeaway that all health coaches and exercise professionals should know.

The body simply doesn’t respond to exercise in the same way in long COVID patients, for reasons that are not entirely understood. They don’t appear to be the result of being out of shape or having experienced any lung or heart issue due to COVID-19 or long COVID. In the exercise intolerance study cited above, for example, patients had a lower oxygen consumption and were short of breath following exercise but had no problems with lung or heart function. What they found was that some veins and arteries were not functioning properly, preventing oxygen from efficiently reaching the muscles, though no one knows why the blood vessel issues occur.

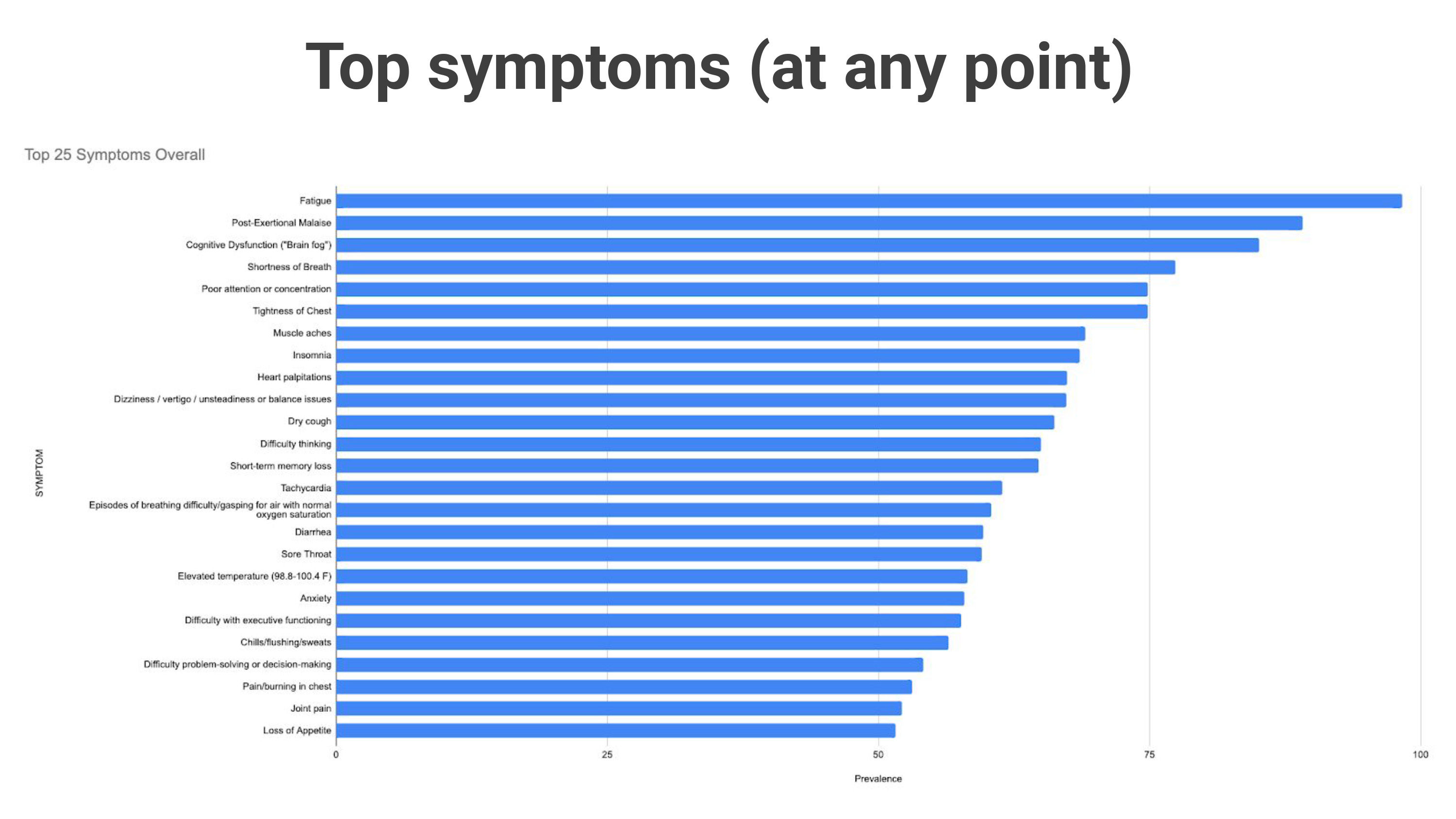

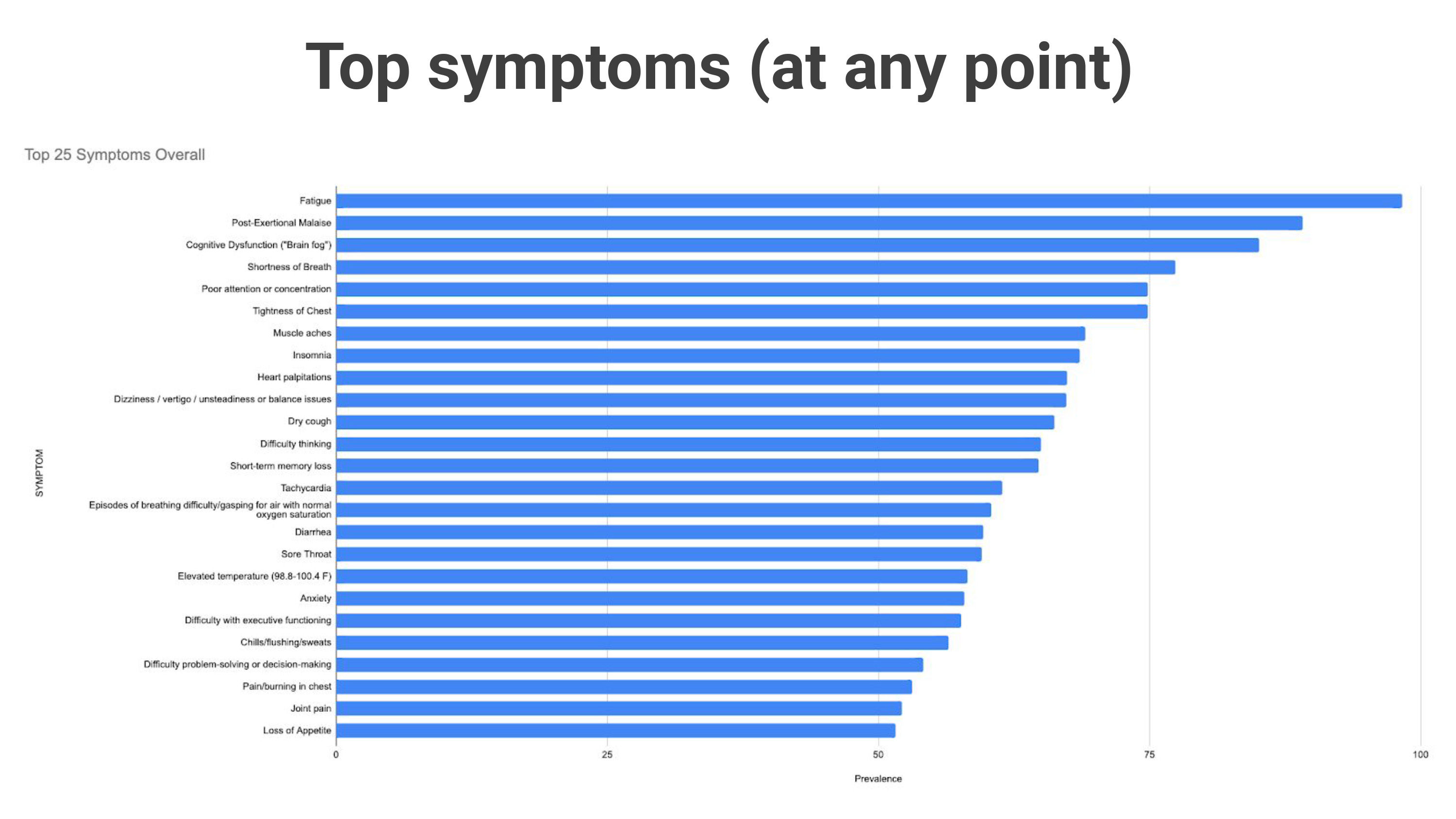

Following those two “physical” symptoms, the list of common symptoms moves into cognitive function, with numbers three and five (with shortness of breath sandwiched in at number four) being cognitive dysfunction (i.e., “brain fog”) and poor attention or concentration (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Common Symptoms of Long COVID. Used with permission from Hannah Davis’s presentation “Long COVID & the Brain” at Drs. Stephanie Peabody and Shelley Carson’s Harvard course Psych #1612, The Science and Application of Brain Health and Performance.

While physical activity is typically credited with improving or helping maintain cognitive function, this is not the case with long COVID patients. “The brain definitely does not respond the same way to physical activity,” explains Davis. “There is a symptom related to post-exertional malaise called post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion, where the brain basically shuts down from exertion.” This is something that she, Dr. Peabody and Dr. Bryant all experienced during their battles with long COVID.

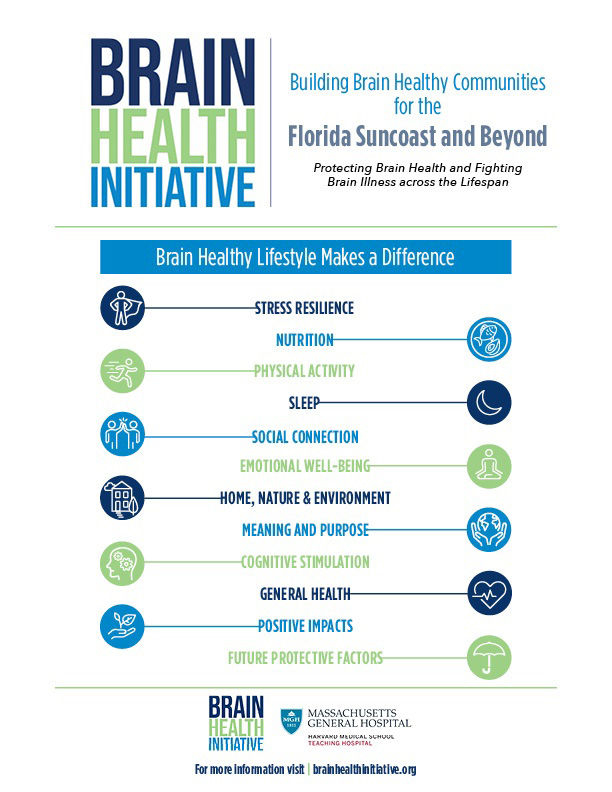

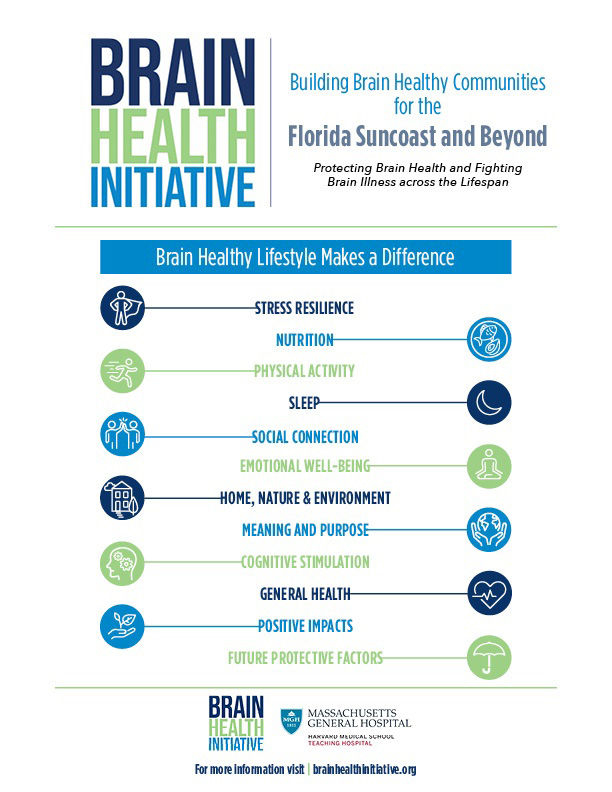

It is important to highlight the fact that you should continue to advocate for healthy lifestyles when working with clients who have long COVID. A healthy lifestyle involves much more than physical activity. “I think it’s really important to understand that for some patients, physical activity is not indicated, but for all patients, the protective factors of brain health, in general, are key supports,” explains Dr. Peabody. “Those lifestyle practices that support physical and brain health are extremely important,” she continues, “not only in terms of prevention, but also in terms of recovery and in terms of symptom reduction” (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Lifestyle Practices for a Healthy Brain

Maintaining a healthy lifestyle can be particularly difficult when managing extreme physical and cognitive malaise. “When you are experiencing this malaise, you want to just lie down and sleep, and you have to be able to do that when it’s necessary, says Dr. Peabody. However, “trying to get yourself, over the course of time, onto a sleep routine that improves quantity and quality is really important.”

Other lifestyle factors that Dr. Peabody highlights include a healthy diet that helps to reduce inflammation, stress resilience through mindfulness and meditation, and a positive attitude about your meaning and purpose, which can have a profound effect on pain levels, energy, mood and cognition.

What This Means to Health Coaches and Exercise Professionals

When it comes to working with clients coming back from long COVID, Dr. Bryant suggests that you focus on your communication skills and take an approach that begins at a very low level of activity and builds slowly from there. The real risk comes from people trying to get back to normal too quickly, so Dr. Bryant suggests adhering “to what you already know about proper progression and abide by the concept of the ‘minimum effective dose’ for each client.”

“Think about the ACE Mover Method™ and ACE ABC Approach™,” offers Dr. Bryant. “Ask helpful questions like whether the client has identified clear triggers that cause them to feel less well and find out if there are any things that they found in working with their healthcare providers or through trial and error on their own that have helped them manage those symptoms once they come on.” He suggests asking clients if they can identify any strategies that may help them avoid any triggers.

“The focus has to be on making sure they’re giving their bodies adequate rest and recovery to ensure they give themselves appropriate reserves where they avoid triggering any symptoms,” continues Dr. Bryant. Speaking of those reserves, Dr. Bryant’s physician used the analogy of a tank of gas to explain this concept. If a person typically functions with a 20-gallon tank of gas, someone with long COVID may have a 5-gallon tank, so they have to be wise in how they use their limited fuel supply. As a health coach or exercise professional, your primary goal when working with long COVID clients should be to avoid emptying that gas tank and leaving them vulnerable to relapse.

Finally, be mindful of the psychological and emotional toll this experience may be having on your clients. There is not a lot of definitive information on the duration and severity of long COVID, so the lingering question of “How long am I going to be like this?” can be emotionally exhausting. The key here is to provide as much encouragement and empowerment as you can, and to help the client build a much-needed network of social support.

In Conclusion

Like most things exercise-related, the relationship between long COVID and exercise is complex and requires a personalized approach. While physical activity may play a part in helping people recover from long COVID, a carefully balanced program that considers their physical, cognitive and emotional well-being is essential. It’s a good idea to remain cautious when working with clients returning to exercise following a bout with long COVID and be sure to always adhere to advice or guidelines from each client’s healthcare provider.

It’s important to remember that, just like with COVID-19, every individual responds differently to long COVID. Therefore, there is no “one size fits all” approach, which means constant communication between you and your clients is vital, as is communication between your clients and their healthcare teams. The long COVID journey is truly individualized, so take the time to understand what your client has gone through, where they are now and where they want to be. Only then can you design an approach that accounts for their symptoms and goals and can safely and efficiently improve their overall health and wellness and help them “get back to normal.”

by

by