It only takes the choice to change.

I just need motivation, then I can change my habits.

A person must make large efforts to positively impact health.

Changing a behavior is a straightforward process.

I’m too old to make a change in my life.

As a health and exercise professional, it’s likely you’ve heard these types of (or similar) statements before. Prior to starting your professional journey, you may have even held some of these beliefs yourself. Before I became a health and exercise professional, I was completely unaware of how behavior change worked and felt that “if a person just wants to change, they can do it.” How misguided I was.

Today, 18 years into my career with a continuous commitment to learn and grow, my goal is to help others avoid the same mistakes I once made. With this article, which highlights common mindset traps clients and professionals experience regularly, I hope you’ll feel reassured that you aren’t alone in falling into those traps—we’ve all been there—but together we can rise above and elevate not only our own individual practices, but the industry as well.

The Client Lens

It’s not surprising that health-coaching clients experience misperceptions about behavior change, particularly because clients often perceive themselves to be “broken” and need to be “fixed.” As a result, they initially believe that working with a health and exercise professional will be the “fix” they need. However, the work of a health coach and a client (as well as the process of behavior change) isn’t nearly that black and white.

Common client misperceptions about behavior change typically fall into one of the following five themes:

Change must be big. Lee Jordan, ACE Certified Health Coach, professor and national presenter, often hears that it takes extraordinary actions to accomplish extraordinary outcomes. However, Jordan shares, “this rarely works, as people become paralyzed (analysis paralysis) trying to determine what and/or how to execute an extraordinary action. The truth is that extraordinary outcomes (especially sustainable ones) are achieved through ordinary actions done daily.”

Chris Gagliardi, ACE Scientific Education Content Manager, agrees. “Behavior change doesn’t need to be anything big or an ‘all-at-once’ effort.” Rather, says Gagliardi, “meaningful change often comes from small but intentional steps.”

The lesson: Small changes add up to big results. Clients get caught in the trap of needing or wanting to address multiple changes all at once. As coaches, we can help our clients focus on what is the most important to them by aligning their goals with their values.

Change is easy. In reality, change is a nonlinear, back-and-forth process. This is one reason the transtheoretical model of behavior change (Figure 1) is often displayed as a winding road or a funnel image as it accurately represents the fluidity of movement through the stages, lapses and all. Humans travel back and forth and up and down along their journeys. That’s expected. It’s normal. It’s part of the process.

Figure 1

“Change is not easy,” says Dennis Sanchez, ACE Health Coach Education and Training Lead. “It is important that when a professional engages in a behavior-change conversation, that they acknowledge up front that the change process is about learning and exploring, not simply achieving a goal. Normalizing the fact that the journey will have lapses (and in some cases relapses) is an important part of helping clients understand that change involves more than just willpower.”

Change is directed by the professional. It’s a common thought that the professional is the “fix,” or the individual who will solve a client’s problem or concern by directing them toward specific actions and prescriptive steps. Behavior change isn’t something that is done to someone; rather, behavior change happens as a collaborative and guided process. “It is important to remember that the behavior-change conversation has to be done at a time that the client is ready to change,” urges Sanchez. “We do not argue for change or fight for change. We simply create the space for the client to explore what change looks like through their eyes.”

As a health and exercise professional, you may be the content expert, but the client is the expert on themselves. For change to occur, you must recognize and respect the difference.

A lapse equals failure. We’ve all felt the twinge of guilt or sadness when we veer off course while working toward a goal. Clients often feel this during their journey when confronted with a bump in the road. This misperception relates to “change is easy” myth discussed earlier. Lapses and setbacks are bound to occur during the process of change, and they are not synonymous with “failure.” You have an opportunity to reframe this message by helping your clients plan for high-risk situations that may threaten their forward progress.

One change is the cure all. “Clients don’t always perceive the unique differences between isolated acts and lifestyle change,” says Gagliardi. “A single change is not curative.” Lifestyle change requires continuous effort and investment over the long term. You can share this message with your clients by assisting them in establishing short- and long-term process goals.

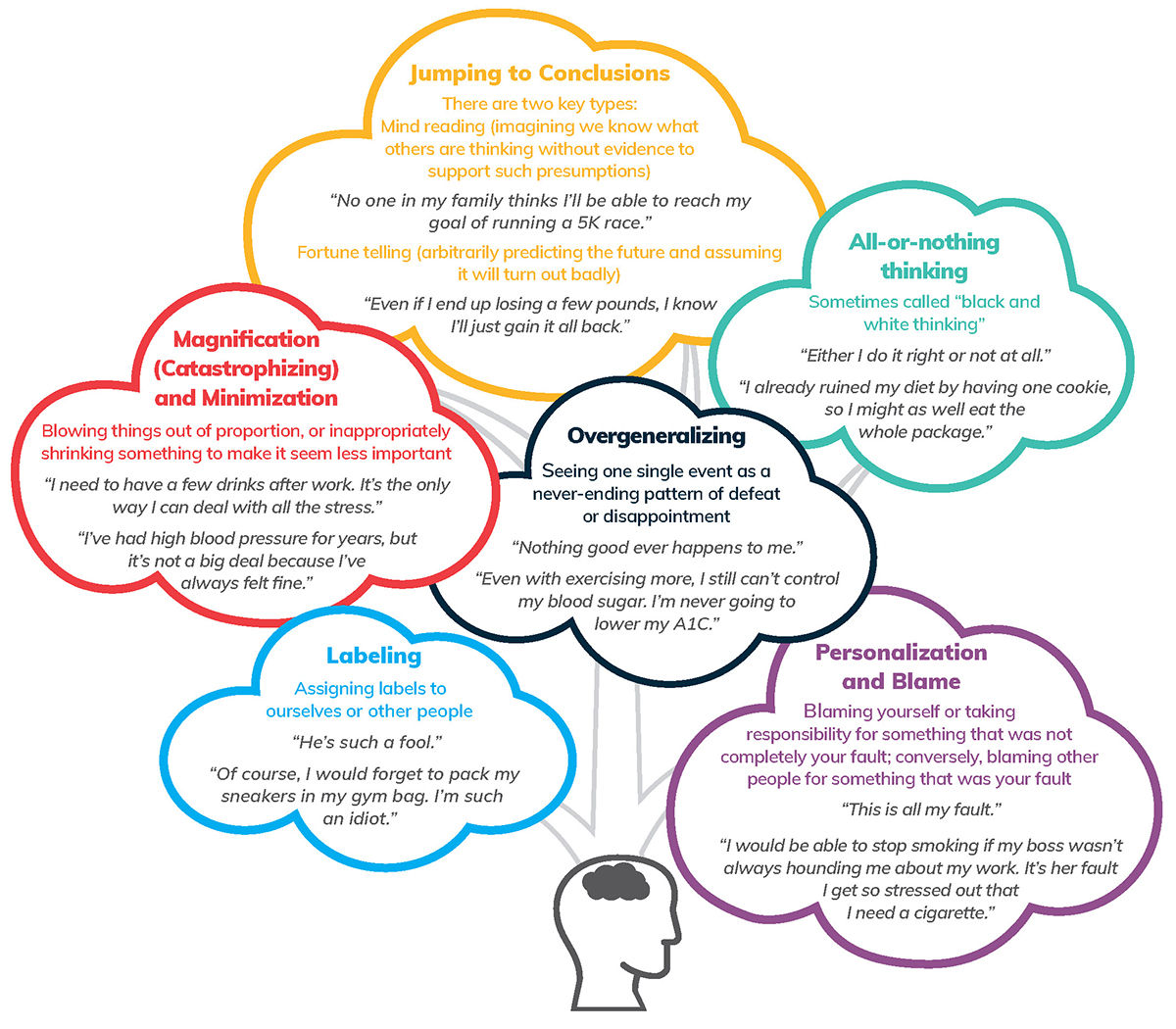

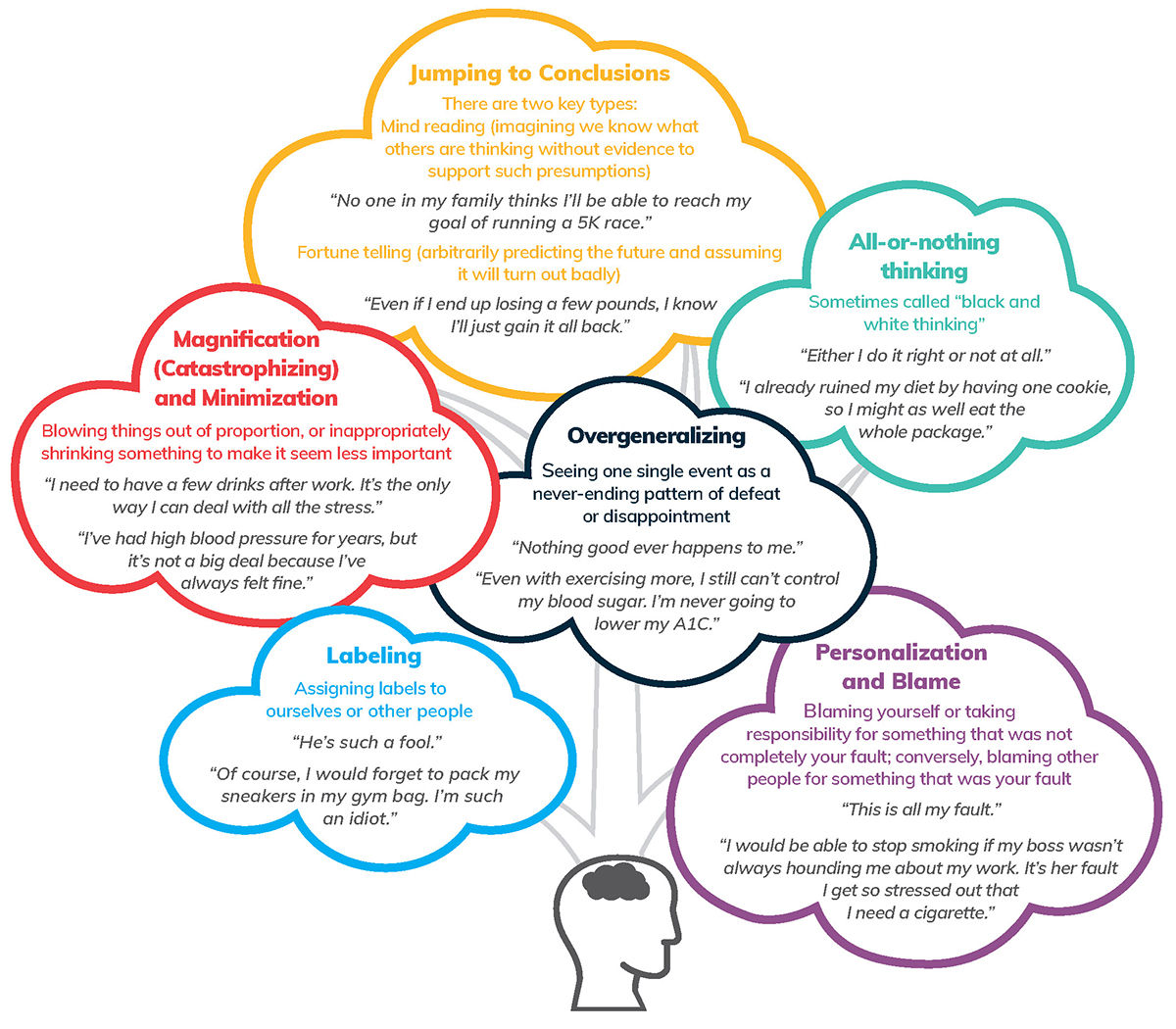

Cognitive Distortions

This graphic presents some additional cognitive distortions that may reinforce your clients’ negative thoughts and feelings and lead to chronically negative and unproductive views of themselves and life.

The Health and Exercise Professional Lens

Misperceptions and misunderstandings aren’t limited to clients and consumers, as health and exercise professionals can also fall into mindset traps that don’t serve them or their clients. Here are six beliefs about behavior change that health and exercise professionals may mistakenly hold:

Knowledge equals behavior change. “It’s not about the knowledge,” insists Gagliardi. “It’s about the application of knowledge and the development of skills that lead to lasting change.” Think about the apple-a-day cliché. It’s far more common for someone to hear “an apple a day keeps the doctor away” than it is for that same person to intentionally consume an apple a day. Therefore, it’s critical that you work with clients on focused skill development and habit formation. Clients require tools, skills and self-monitoring to continue making progress.

I must know it all to be effective. Our practice is ever-changing and our skills, much like our clients’ skills, are always being sharpened and refined. We will never know it all, which is a good thing because it means our field is continuing its evolution and making discoveries as it shifts and grows. The biggest and most important ingredient is passion and commitment to traveling along this journey of change with your clients. “One of the hardest parts of using our skills is to acknowledge that you do not have all the answers,” says Sanchez, “and that the person you are speaking to will always be better equipped to voice what is possible for them.”

More is better. How many of us have thought this during a session with a client? We sometimes neglect to appreciate the silence and hold still in that space. “Sometimes more is just more, not better,” explains Gagliardi. “It’s easy to fall into the righting reflex or give advice. What we need to do is sit quietly, stay present and allow time for the client to reflect. Embrace the pregnant pause, as it is a revealing moment.”

The coach is responsible for program success. Gagliardi used to feel like he had failed his client if they didn’t meet their objectives. “If my client wasn’t successful, I made the inward judgement that I didn’t do something right, that I failed,” he admits. There are, however, many reasons why a program may not be effective. Maybe a client’s goals aren’t aligned with their values. Or the timeline is too rigid and doesn’t leave room for flexibility or change. Furthermore, key elements of social supports may not be identified or utilized. Sometimes a program isn’t successful because of adherence or compliance, or maybe the chemistry between the client and the coach is just “off.” The success of any program (or any change) does not rest entirely on a coach’s shoulders. Change is a collaborative experience.

Coaching skills are generalizable to family and friends. According to Sanchez, a coach can mistakenly believe that they can use their behavior-change skills to influence or change family members and friends. He offers this word of caution: “Behavior-change conversations can only happen under one circumstance—when the client/friend/family member has given you permission to coach. Behavior-change skills are not designed to manipulate someone into change, nor are they designed to be used unsolicited.” In short, for change to happen, it must come from the individual wanting to change, not from the professional telling the individual to make a change. The change must also be personally valuable and relevant to the client or individual.

Motivation is the pinnacle. A coach may mistakenly feel as if the key to changing a behavior is all about motivation, observes Jordan, and that a person simply needs to focus on that aspect. In reality, “motivation is complex, and it changes for people over time. Keeping ‘enough’ motivation is very challenging and a bit like a game of ‘whack a mole.’ A better approach is to address the habit being built by simply reducing its difficulty to meet a person’s shifting motivation level.” By doing this, explains Jordan, the client can lean into frequency, which is key to habit design, “leading to mastery and behavior change.”

In Summary

There are misconceptions associated with every topic we work within: nutrition, exercise, fitness, weight loss, chronic disease management, etc. The source of the misconception may include unqualified influencers on a social media channel, poorly communicated science concepts or our clients’ (or our own) lack of understanding or experience. As health and exercise professionals, we grow in our understanding over time as we gain more experience, make (and embrace) mistakes (some more significant than others), and recover from those errors. And we can do the same for our clients. We can help them grow in their understanding and acceptance that behavior change is a process that requires patience, self-grace and continual commitment.

by

by