ACE-sponsored Research: Are Activity Trackers Accurate?

![]()

Activity trackers are everywhere these days, but when it comes to tracking steps and calories, are they really accurate? A new ACE-sponsored research study examined five popular activity trackers to determine whether or not they are worth your time or your money.

It’s that time of year, when everyone recommits to a more healthy lifestyle. Increasingly, people are turning to activity trackers—electronic devices that track everything from caloric expenditure to quality of sleep—to help them stay on course and meet their health and fitness goals.

An estimated 19 million devices were in use in 2014, and that number is expected to grow exponentially over the next few years. In fact, a recent report by Juniper Research predicts that the use of activity trackers—also called fitness wearables—will triple by 2018.

While all this new technology is really cool and some of it is really fun to use, very little published research exists demonstrating the accuracy or validity of these devices. How closely do they predict caloric expenditure or track the number of steps taken? Given the increasing prevalence of these devices, the American Council on Exercise enlisted a team of researchers from the Clinical Exercise Physiology program at the University of Wisconsin—La Crosse to examine five popular activity trackers to determine whether or not they are worth your time or your money.

The Study

For this study, five popular activity trackers were chosen: Nike+ Fuelband ($99-$149), Fitbit Ultra ($99), Jawbone UP ($99), BodyMedia FitCore ($99) and the Adidas MiCoach ($199). [Note: Since this study was completed, BodyMedia was purchased by Jawbone.]

Researchers recruited 10 healthy men and 10 healthy women, ages 18 to 44, to participate in the study, which was divided into two parts: one to measure energy expenditure and the other to measure the number of steps taken. The protocol was the same for both studies and they were conducted concurrently.

Along with wearing the activity trackers, subjects wore a portable metabolic analyzer and the NL-2000i pedometer, which has proven reliability, to make an accurate determination of calories burned and steps taken. Each subject performed a series of different exercises wearing all of these devices at the same time; the testing was conducted in two separate 50-minute sessions.

The first session included walking and running on a level treadmill. Each subject walked at a self-selected speed for 20 minutes and then rested for 10 minutes before running for 20 minutes at a self-selected pace.

The second session was completed on an elliptical crosstrainer that worked both the arms and legs; participants completed 20 minutes of exercise at a self-selected intensity. After a break, subjects performed sports-related exercises, including ladder drills, basketball free throws, T-drills and half-court lay-up drills.

After completing both sessions, the values were recorded from each device and compared to the portable metabolic analyzer energy expenditure values and the number of steps taken.

The Results

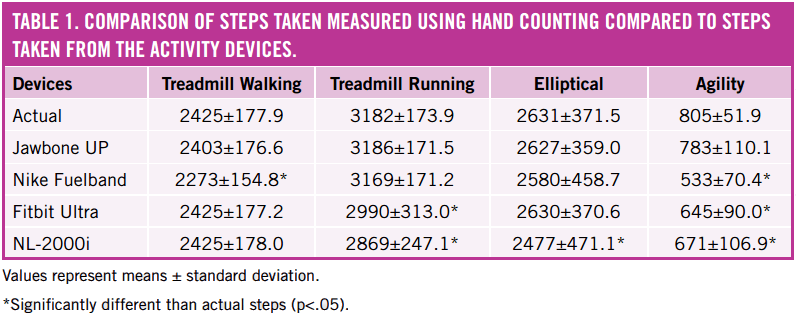

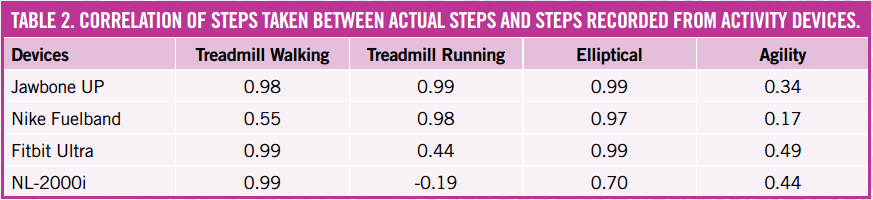

When it comes to tracking steps, the activity trackers were pretty reliable, says lead researcher Caitlin Stackpool, M.S., with the accuracy depending on the type of exercise being done. All five devices predicted within 10 percent accuracy the number of steps taken during treadmill walking and running, as well as during elliptical exercise (Tables 1 and 2).

During agility drills, however, there was a larger underestimation, but Stackpool explains that this is likely due to the variety of more complex movements. Smaller or quicker steps taken may not always register on the activity trackers, and also appeared to lead to less arm movement, which would then affect the accuracy of the activity trackers that were worn on the arms or wrists (the Fitbit is the only device in this study that is not worn on the wrist).

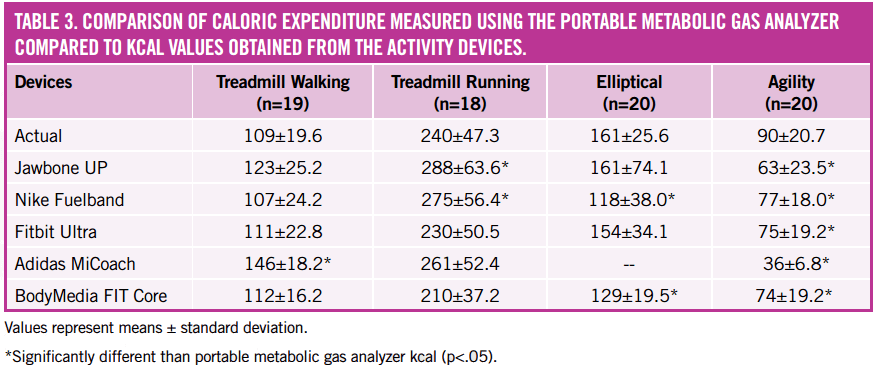

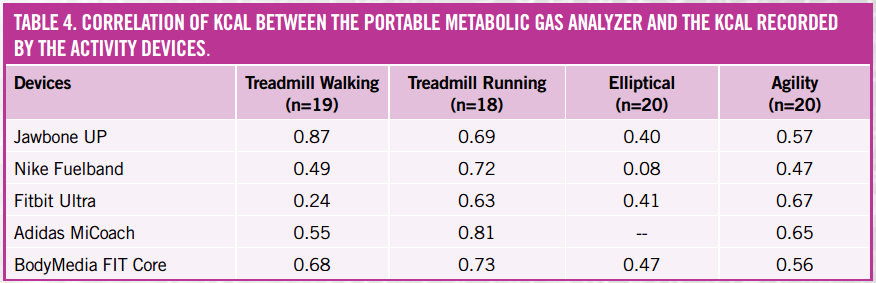

The devices were a little less accurate when estimating energy expenditure (Tables 3 and 4). Recording energy expenditure is a more complex process, explains John P. Porcari, Ph.D., head of the University’s Clinical Exercise Physiology Department. It also involves incorporating data measured by the device into a regression equation within the devices’ software. This is likely why there was more variation in the recordings.

The difference between measured and predicted kcals ranged from 13 to 60 percent, with some devices overpredicting and some devices underpredicting. None of the devices were accurate across all the activities for recording calories burned, so picking an activity device to record caloric expenditure may not be the best option.

The Bottom Line

When choosing a device, researchers advise consumers to think about the information they want to track. If looking at steps taken, the Jawbone UP appears to be the best activity device to choose. If an individual is more concerned about calories, there was a wide variety of results, depending on what type of activity was being performed.

“Most devices are pretty good for measuring steps taken during traditional activities,” says Porcari. “Once you start getting outside of that—like elliptical or sports-related movements—it becomes harder to detect actual steps taken.”

“These activity trackers work best for lower-intensity activities such as walking,” adds Stackpool, who thinks these devices are especially beneficial to new exercisers. “It gives them a way to assess where they are, set goals and see improvements.”

And what about caloric expenditure?

“Predicting calorie burn is a complicated thing,” explains Porcari. “People vary how they move their arms, for example. Some are more efficient and some are more variable. Most devices probably won’t get within 10 to 15 percent accuracy because there is simply too much biological variability.”

But that doesn’t mean there still isn’t a benefit to using an activity tracker, says Stackpool. “Activity trackers show people how active they are throughout the day. Being sedentary 90 percent of the time and performing 30 minutes of exercise does not necessarily make a person ‘active.’”

By wearing the devices all day, people can see whether or not they need to add more activity throughout the day. In fact, according to Porcari, “Studies show that people are 30 to 40 percent more active when they use activity trackers.” So, perhaps the absolute accuracy of the device is less important than the fact that they do a good job of getting people up and moving.

And that, says Stackpool, is the take-home message for consumers: Do whatever it takes—whatever works for you—to be more active. If wearing an activity tracker helps you do that, your best bet is to choose a device based on comfort, ease of use and whatever additional features might appeal to you.

More Articles

- ProSource™: January 2015

How You Can Help Clients With Chronic Pain

Health and Fitness Expert

- ProSource™: January 2015

New Year, New Opportunities: Becoming a Group Fitness Instructor

Health and Fitness Expert

- ProSource™: January 2015

When Intuitive Eating Is Counterintuitive: How to Help Clients Learn to Listen to Their Bodies

Contributor

- ProSource™: January 2015

Under-the-radar Strategies for Marketing Fitness on Social Media

Health and Fitness Expert