Come on! You can do it! These are familiar words to health and fitness professionals, as we consistently attempt to motivate our clients. It often seems to work, particularly when we are right there, standing next to her or working out with him.

But what REALLY motivates our clients to exercise when they are not with us? Do we hope that our inspiring, strong voices ring in their ears when we are not with them? Do we assume that our passion for fitness can transfer onto our clients so they will love fitness and exercise as much as we do? These are key questions often overlooked or not explored deeply enough.

And yet we wonder why so many of our clients do not return to class after three weeks, or why our once-enthusiastic client decides to not continue with personal training after the initial six-session introductory special. Understanding the deeper elements related to human motivation could transform how we approach our clients and design successful fitness programming. It will also inform how we purposefully interact with our clients to help them develop intrinsic motivation for exercise for greater long-term adherence.

The comprehensive theory of human motivation, Self-Determination Theory (SDT), developed by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan (1985), suggests that intrinsic motivation, the most internalized form of motivation, is dependent on the fulfillment of three basic human needs: autonomy, competence and relatedness. If these needs are indeed fulfilled, self-determination to engage in a particular behavior is much more likely.

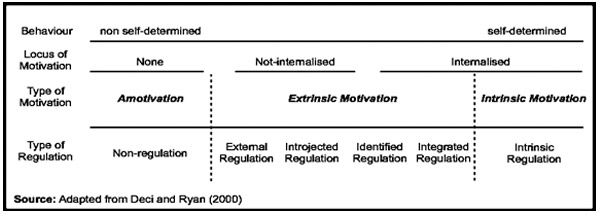

To illustrate more clearly the internalization process of motivation, Deci and Ryan (2000) developed the Self-Determination Continuum, which nicely showcases three main types of motivation: amotivation, extrinsic motivation and intrinsic motivation.

Amotivation refers to the complete absence of motivation for a particular behavior. Extrinsic motivation contains four subcategories, which, from left to right, increase in internalization of motivation. External regulators include rewards, such as money, prizes or perhaps status like winning a competition. Avoiding penalty or applying external force to complete a certain behavior are also considered external regulators. Doing a particular behavior because of guilt or wanting the approval of others drives introjected regulation and is slightly more internalized than external regulation. Someone who experiences identified regulation may participate in a behavior because it may be beneficial in achieving an important goal; however, the activity may still not be enjoyable to this individual.

The most internalized form of extrinsic motivation is integrated regulation. Here, the individual experiences an agreement between personal values or beliefs and the behavior. For example, one may see that exercise is beneficial for his or her overall health and because this individual values health, engaging in exercise is agreeable, even if it is not enjoyable.

At the very right of the continuum is intrinsic motivation. Someone who is intrinsically motivated does not really need encouragement because the activity itself is enjoyable. Typically, this individual’s needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness are satisfied here. This client may simply need you as a means for learning new skills, continued relatedness and challenge.

Here are three practical tips for how you can translate this knowledge about human motivation into practice in the context of exercise to foster greater long-term adherence for your clients:

1. Conduct an honest self-evaluation of how you deal with the motivation for exercise with your clients. Do you assume that they are intrinsically motivated? Do you know what motivates your clients? Have you thought about human motivation before? What methods do you use to motivate your clients? Which methods have actually worked?

2. Consider integrating motivational assessment tools during your initial screening and testing process with your clients, such as the Exercise Motivations Inventory (EMI-2) or the Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire (BREQ-2).

3. Develop a specific plan, based on the assessment, to assist with the internalization process of motivation for exercise for each client along with your exercise/fitness plan. How can you increase and enhance your client’s autonomy, competence and relatedness in the context of exercise and physical activity? How can you increase the agreement between personal values and beliefs and exercise? Are your methods of external regulators hindering or halting your client from internalizing motivation for exercise?

Take your fitness practices to a deeper, more effective level by integrating theoretical and practical concepts of human motivation related to exercise behavior change as you start the New Year 2015. Come on! You can do it!

by

by