Staying in your Lane

We've all been there—stuck in the "fast lane" behind someone who's driving slowly. While the unwritten rules of the road may tolerate a slow driver coasting in the fast lane, such concessions within the fitness industry have considerable ramifications.

For example, consider the health and exercise professional who applies a manual, hands-on approach to solve his or her clients’ pain problems. Make no mistake, the influence that manual therapy can have on an individual’s chronic pain can be profound, but this lane of "hands-on treatment" is reserved specifically for those with highly specialized training and regulated licenses.

For the health and exercise professional, navigating the turbulent waters of chronic pain requires one to become proficient with designing strategic and personalized exercise programs.

Primary Objectives: Your 80/20

Working with individuals in chronic pain is undoubtedly complex. It can sometimes feel like a labyrinth of ambiguity, particularly when clients begin referencing their symptoms. What’s more, coupled with subjective symptoms is the challenge of deciphering each client’s assessment results. It can sometimes be difficult to even know where to begin.

This is where scripting specific objectives and adhering to the 80/20 principle can yield enormous dividends. This principle asserts that 20% of one’s focus will determine 80% of the desired outcome. In relating the 80/20 principle to programming and analyzing assessment data, a key question to consider becomes: "What were the biomechanical constraints that consistently showed up in the majority of the client's assessments?"

For example, was the client’s left hip lacking sufficient amounts of internal rotation no matter which global assessment was performed? Perhaps the client’s inability to load in the frontal plane was observed in his or her single-leg stance, anterior lunge and gait assessments.

These are examples of identifying consistent, inefficient movement patterns. These patterns are what Pain-free Movement Specialists refer to as their "big rocks," and it's these big rocks that not only guide the specific objectives accompanying effective program design, but also influence the order and sequence of exercises.

A Framework for Exercise Progression: Levels A-D

Just how significant is the sequencing of exercises? Think about what would happen if you had the correct numbers to unlock a vault, yet you were unaware of the order and sequence in which to place them. Without proper order and sequencing (syntax), the numbers are essentially useless. The vault will remain locked.

The same principle holds true with programming. Each exercise should prepare the body for the next. Therefore, logic and intent guide each of the exercises selected. This process can be broken down into four levels of exercise progression, each of which ascend through the cognitive, associative and autonomic phases of motor learning.

Level A Corrective Exercises

Level A corrective exercises are floor-based exercises (prone or supine) that provide an optimal environment in which to facilitate new motor learning strategies. The climate created here focuses on the cognitive phase of motor learning, enhancing each client’s intrinsic awareness, while simultaneously establishing trust between you and your client.

Level B Corrective Exercises

Level B corrective exercises are performed on all fours (quadruped), kneeling and/or from a seated position. The ascending complexity here provides a novel movement strategy by associating it with an existing central motor program already stored in the client’s movement "database." This is where the client enters the associative phase of motor learning.

Level C Corrective Exercises

Level C corrective exercises are standing exercises that provide at least three points of reference for the body. The objective here is to create an environment where the body is upright and parallel to the forces of gravitational pull. These exercises provide an optimal environment to begin transitioning from the cognitive and associated phases of motor learning toward the autonomic phase.

Level D Corrective Exercises

Level D corrective exercises are performed in a bipedal or unipedal stance with a maximum of two points of reference. These exercises are designed for the autonomic phase of sensory-motor integration and should require no need for cognitive processing. Minimal verbal instruction/coaching is required. The interplay of gravity, ground reaction force, mass and momentum, acceleration and deceleration, various myofascial slings and multiple body segments are all elements that may be associated with level D exercises.

Each individual views the world through a different lens, ultimately shaping and molding his or her unique perspective. This is particularly relevant when working with clients in pain. And because pain is much more than just a sensory mechanism, experiencing pain on a consistent basis can negatively transform an individual’s thoughts, feelings, perceptions and beliefs regarding movement, influencing not just biological, but psychological and social factors as well.

Therefore, an important question to consider when navigating program design is, “What does a successful corrective intervention look like to the client?” To some, success is walking upstairs with confidence, free from knee pain. To others, standing for prolonged periods of time while cooking dinner is the desired outcome.

The art of a successful intervention involves understanding and validating each client’s emotional, psychological and social concerns, while addressing his or her unique biomechanical needs. Together, these ingredients yield a comprehensive framework toward designing a strategic and personalized fitness program strategy.

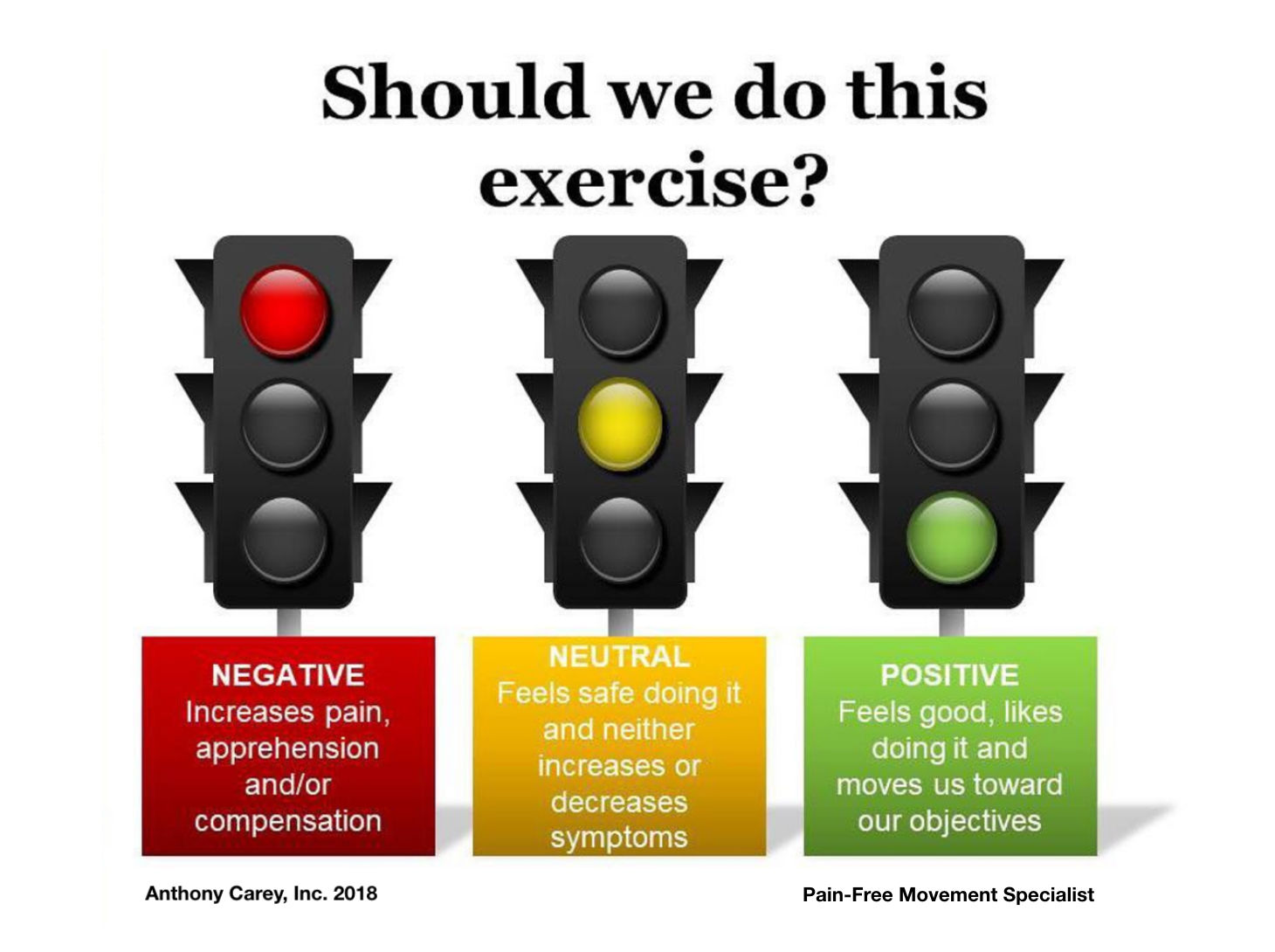

The image below provides clients with a graded scale of psychosocial autonomy and self-reliance where the re-education of movement modulation and exercise tolerance is based on their own intrinsic awareness and overall sense of safety.

Summary

Above all, the genesis of creating change is deeply rooted within a health and exercise professional’s awareness of the multidimensional interaction between biological, psychological and social factors, all of which contribute to an individual’s pain experience.

And should you ever find yourself adrift, floating down the river of program-design insecurity, remember that working with individuals in pain is a reciprocal, collaborative process. It’s a script in which each client is cast as the main character in his or her story, with the health and exercise professional functioning as a guide, a fellow traveler guiding each individual toward arriving safely (and pain-free) at the desired end.

Reference

Koch, R. (2011). The 80/20 Principle: The Secret to Achieving More With Less. Danvers, Mass.: Crowne Publishing Group.

by

by

by

by