This past year has been challenging for kids. From online learning to physical distancing and everything in between, most girls and boys have had a difficult time keeping up with their schoolwork, maintaining social relationships and accumulating the recommended minimum of at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) daily. Indeed, the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has impacted the lives of youth in an unprecedented manner and well-founded concerns about their physical and mental well-being are increasing.

A Pandemic within A Pandemic

Not too long ago, exercise epidemiologists used the word pandemic to describe troubling trends in physical inactivity around the world (Kohl et al., 2012). Now, we have a pandemic of physical inactivity within a pandemic of COVID-19 and both of these conditions will get worse unless action steps are taken to help prevent their spread (Wilke et al., 2021).

Even before COVID-19, a vast majority of youth did not accumulate at least 60 minutes of MVPA daily, and the situation is even worse today. Throughout the COVID-19 outbreak, there has been a decrease in physical activity and an increase in leisure screen time among girls and boys (Moore et al., 2020). Further, performance losses in cardiorespiratory fitness (e.g., progressive aerobic cardiovascular endurance run) and muscular fitness (e.g., push-ups and sit-ups) in school-age youth are now being reported (Jurak et al., 2021; Wahl-Alexander & Camic, 2021).

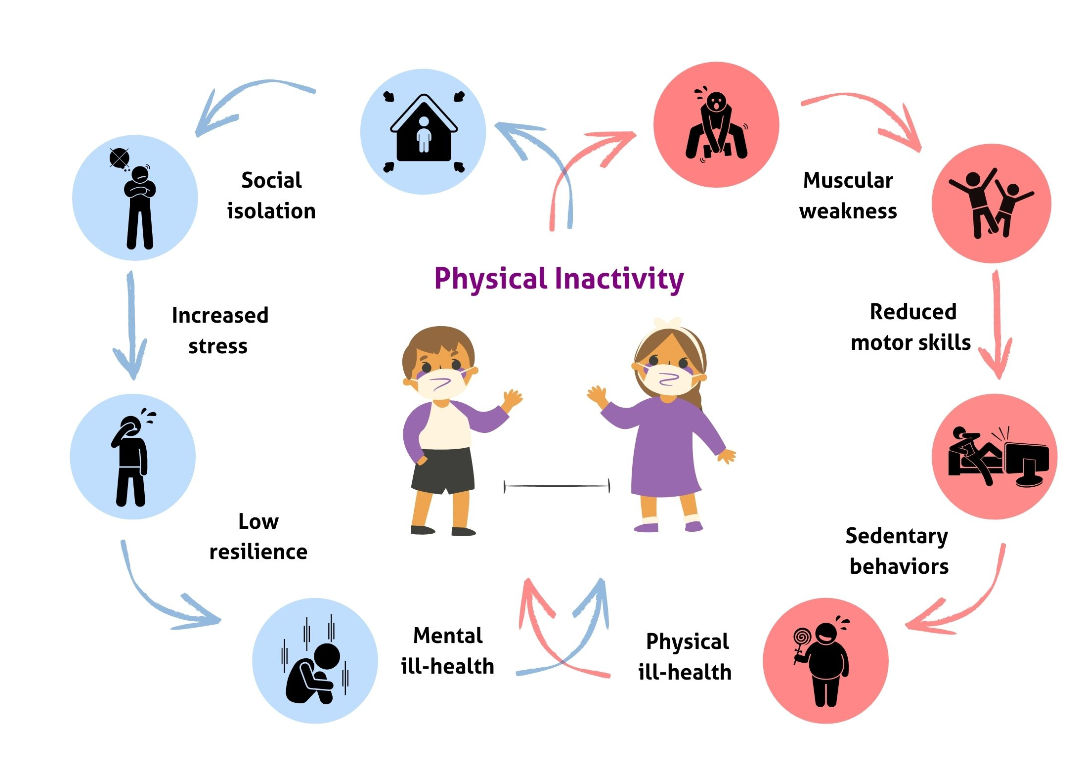

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, time spent at parks and beaches is down and opportunities for kids to be active at school and in fitness centers have decreased dramatically. Given the strong associations between MVPA and health outcomes, the physical and mental health of youth may be compromised due to a reduction in healthy movement behaviors throughout the day (Figure 1). Prolonged periods of physical inactivity can result in muscular weakness, poor motor skills and an inevitable decline in a child’s confidence and competence to engage in nonessential MVPA with energy, vigor and interest.

In turn, youth may spend more time engaged in sedentary behaviors since movement becomes more difficult (and sometimes embarrassing) when their body mass index reaches unhealthy levels. Concurrently, mental health issues may begin to emerge due to limited social interactions and increased stress during periods of home confinement. Impairments in mental-health resilience, due in part to reductions in meaningful social interactions during challenging exercise and sport activities, may increase the risk of mental health issues because youth may be less able to cope with life-changing circumstances.

Physical Activity Is a Polypill

A polypill is a drug that combines multiple active ingredients and can be used to treat a variety of conditions. MVPA can be considered a polypill due to the multitude of physical and mental health benefits that can result from active transportation, outdoor play, physical education, planned exercise and sport activities. Gradually returning to a more active lifestyle at school and in the community can be therapeutic for youth who may have spent more time in front of a screen over the past year than at a playground, fitness center or sports field. While parents continue to face many challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, returning to a more active lifestyle can benefit the whole family.

However, the return to a more physically active lifestyle should not begin with competitive sports. The unexpected year-long pause has resulted in worrisome decreases in physical fitness and, consequently, most participants may not be prepared for the demands of sports practice and competition (Mulcahey et al.,2021). Prior to COVID-19, pediatric researchers raised concern about the declining levels of muscular strength in modern-day youth (Faigenbaum et al, 2020), and now there is a real risk of compounding the impact of physical inactivity with an upsurge of sports-related injuries in young athletes. According to Nicholas DiNubile, MD, an orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine and ACE’s Chief Medical Adviser, “there could be a rash of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries and many other sports injuries, both traumatic and overuse, in young athletes this fall unless preparatory strength and conditioning becomes the new normal.”

Since a certain amount of muscular strength is needed to jump, sprint, kick and throw proficiently, youth with inadequate levels of muscular strength may be less likely to participate in exercise and sport activities and, if they do participate, more likely to suffer an activity-related injury. Supervised and well-designed interventions that target strength deficits have proven to be effective in reducing youth sports injuries (Petushek et al., 2019).

This type of fitness programming, which includes resistance training as well as agility and jump training, is urgently needed to prepare today’s youth for participation in sports. As efforts to integrate MVPA back into the lives of youth are beginning to take shape, exercise professionals have an extraordinary opportunity to build an infrastructure that recognizes the foundational importance of muscular fitness early in life.

Interested in learning more about youth fitness? Become an ACE Youth Fitness Specialist and you will be well positioned to positively impact the health and well-being of children.

10 Tips for Youth Fitness Specialists

- Integrate strength- and skill-building activities into fitness programs

- Encourage outdoor play at parks and playgrounds

- Celebrate efforts to be active throughout the day

- Promote social interactions and encourage youth to help each other

- Keep the fun in youth fitness

- Focus on developing positive lifestyle behaviors, including adequate sleep

- Be a good role model and set an example of expected actions and behaviors

- Encourage parents and caretakers to incorporate physical activity into the daily routine

- Support daily physical education from K-12

- Work with sports medicine professionals to reinforce the benefits of neuromuscular training

References

Faigenbaum, A., et al. (2020). Making a strong case for prioritizing muscular fitness in youth physical activity guidelines. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 19, 12, 530-536.

Jurak, G., et al. (2021). A COVID-19 crisis in child physical fitness: Creating a barometric tool of public health engagement for the Republic of Slovenia. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 644235.

Kohl, H., et al. (2012). The pandemic of physical inactivity: Global action for public health. Lancet, 380, 294-305.

Moore, S., et al (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: a national survey. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17, 1, 85.

Mulcahey, M., et al. (2021). Sports medicine considerations during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 49, 2, 512-521.

Petushek, E., et al. (2019). Evidence-based best-practice guidelines for preventing anterior cruciate ligament injuries in young female athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 47, 7, 1744-1753.

Wahl-Alexander , Z., & Camic, C. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on school-aged male and female health-related fitness markers. Pediatric Exercise Science, 33, 61-64.

Wilke, J., (2021). A pandemic within the pandemic? Physical activity levels substantially decreased in countries affected by COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 5, 2235.

by

by

by

by