Behavior change is hard. Not only does it require eliminating habits that bring us momentary pleasure in the pursuit of distant goals, but we must often confront those parts of ourselves that make us feel uncomfortable or ashamed.

When clients come to us with goals of improving nutrition or activity habits, these underlying feelings of discomfort often arise. Our responses as coaches can help or hinder our clients’ behavior-change processes. To foster healthy, sustainable change, it’s not enough to simply offer nutritional education or exercise programming. Rather, we must be able to create a space for our clients that allows for the discussion and dismantling of their fears around changing their eating, movement and other lifestyle habits.

This article explores the challenges many clients face when addressing their health behaviors and offers strategies health coaches and exercise professionals can use to navigate them.

Fear, Insecurity and Self-Doubt

Many clients who elicit the help of a health coach have struggled with changing their eating or exercise habits in the past. This may leave them doubtful of their ability to successfully change.

“It’s extremely frustrating for clients to feel they’ve made countless attempts to change a behavior or achieve results that seem elusive,” says Liana Tsirklin, MS, a health coach at Cigna. Clients often withhold these past behavior-change attempts due to embarrassment or discomfort. This concealment can hinder the client-coach connection and limit a coach’s full understanding of a client’s history.

“What most of my clients don’t share is that they’re afraid of failing,” says David Rodriguez, founder of Center Circle Health and Fitness. “A lot of people with chronic health issues, especially when it comes to diabetes or obesity, have tried over and over again to improve their health by dieting and exercising. This fear of failure speaks to an existential feeling of dread, that they are destined or doomed to be fighting this losing battle for the duration of their life,” he says.

To combat these issues, clearly communicate acceptance and non-judgment. Posing questions about clients' past efforts, without scrutiny or criticism, allows these areas to be fully explored. Clients abandon behavior-change plans for viable reasons and understanding these reasons will help both you and your clients construct more appropriate plans for their future.

Further, clients may have fears around the adoption or abandonment of certain behaviors. “I think our biggest fears lie in abandoning habits we’ve had for years, even decades,” explains Tsirklin. “It’s scary to get rid of something comforting and not know what will replace it.”

Feelings of fear and trepidation often hinder the successful adoption of healthy habits. Self-efficacy, one’s belief in his or her ability to master a particular behavior or skill, is highly related to healthy eating habits and physical activity (McAuley and Blissmer, 2000). Research suggests that self-efficacy is important not only in the adoption of new exercise habits, but also in adherence (McAuley and Blissmer, 2000). Similarly, high dietary self-efficacy is related to improved eating habits over time (AbuSabha and Achterberg, 1997). As such, self-doubt, which is antithetical to self-efficacy, is a major roadblock in the development and maintenance of improved eating and exercise behaviors.

A critical step in overcoming self-doubt is acknowledging its existence. “Inquire about the origins of this doubt,” urges Tsirklin. “Was there a related or unrelated ‘failure’ earlier in the person’s life that made them lose their confidence in their abilities to achieve their goals and succeed?” Digging into these stories provides an opportunity to affirm and support your client. One method for enhancing self-efficacy is via verbal persuasion, where coaches or trainers simply encourage their clients and let them know they believe in their ability to succeed. “Often, when clients come to us, it is a last-ditch effort, as they feel they have tried everything,” says Tsirklin. “When we support them and express our confidence, it can help them develop confidence of their own.”

The adoption of small, manageable steps is crucial in building self-efficacy in the early stages of behavior change. Clients, understandably excited about a lifestyle shift, often want to implement dramatic behavioral changes. However, large-scale modifications are more likely to lead to overwhelm, burnout and abandonment of new behaviors.

“Clients often have a fear of making mistakes, as if going off plan or anything less than complete adherence will negate their progress,” says Rodriguez. “They often view their behaviors as black-and-white, when in reality it’s a spectrum of shades of grey. Helping them learn that their health is the result of the aggregation of their decisions, rather than the result of a single decision, can relieve the anxiety of needing to be 100% on plan all the time.”

Further, mastery experience, which comes from successfully completing small steps, is an integral strategy for reinforcing self-efficacy (Artino, 2012). When clients achieve small successes, they are able to build on these feelings of accomplishment to create longer-lasting change.

If the fear and self-doubt go unchallenged, however, they can become insidious, holding your clients back from fully embracing change for fear of falling short. In discussing their concerns, you can challenge their self-limiting beliefs and build a supportive system that allows for the exploration and adoption of healthier behaviors.

Explicit Verbiage and Implicit Beliefs

The words you use and the beliefs you convey impact what your clients divulge. When clients feel they can share their successes and failures without judgment, they are more likely to be forthcoming about their process.

“Our clients look up to us and see us as experts. They may see us through a lens of perfection, which generates a fear of judgment. As such, they may not be truthful about their actions, which ultimately doesn’t allow us to help them reach their full potential. We must establish a judgment-free zone to make way for honesty, transparency and true progress,” says Tsirklin.

One useful technique is conveying the message that your client cannot fail. Many clients who fear “failing” their coach withhold slip-ups. To reduce this occurrence, have a discussion about the behavior-change process. Describe the normalcy and likelihood of setbacks, and share that any perceived “failure” is just a learning experience.

For example, if a client comes to a session without having completed a single day of his or her intended physical-activity routine, you can frame this as an opportunity for learning. You might question what barriers got in the way, how the client felt about the missed activity sessions or what would make the activity feel more doable. Similarly, if a client comes to you claiming he or she overate one evening, you might explore how the client was feeling. Did he or she have a stressful day? Did the client argue with his or her spouse? Or you might pose questions around physical precursors. Did the client skip out on breakfast or eat a light lunch? In this way, clients are more likely to be honest about their behavior and better understand their triggers.

Your nonverbal communication also affects client behavior. When a client discloses a deviation in his or her plans, what do your body language, tone of voice and eye contact convey? Does the client feel unconditionally accepted, despite his or her behaviors? Psychologist Carl Rogers, founder of client-centered approaches to psychotherapy, suggests that the ideal condition to promote change occurs when clients feel safe and supported and when they believe their environment allows them to work through their problems openly. Rogers notes three conditions that create this setting: empathy, acceptance and genuineness (Csillik, 2013). Acceptance involves a practitioner’s unconditional positive regard for his or her client, such that the valuation involves the individual’s inherent worth as a person, rather than the behaviors he or she performs. When a client is not offered this kind of acceptance, progress is disrupted (Csillik, 2013).

“It’s important to validate clients’ feelings of apprehension toward change,” says Rodriguez. “Change is scary, but it is also important. You can’t expect to be different doing the same thing you’ve always done. I remind clients that if they try something and it doesn’t work, that doesn’t mean it’s a failure. All they’ve done is create data.”

By showing our clients unconditional positive regard, irrespective of their adherence to eating or exercise programming, we establish a safe setting where clients can openly grapple with their struggles and move in the direction of authentic change.

Weighing the Pros and Cons

It can be mystifying to coaches when clients struggle to change their eating or exercise habits. The advice and activities we outline are clear and evidence-based and we devise them to fit within the context of our clients’ lives, so it’s easy to feel frustrated when they forgo them.

One often-overlooked consideration is the benefit clients receive from performing their current behaviors. All behaviors, even seemingly unhealthy ones, serve some need or they wouldn’t be performed. When we struggle to understand why clients continue to perform unhealthy behaviors they claim to want to give up, we should question what benefits they are deriving from those behaviors.

For example, a client plans to go to the gym after work three times a week, but at your next meeting, the client shares that he or she went home to watch television and snack each night instead. Rather than questioning why the client didn’t make it to the gym, you could explore what needs are being met by the client’s current behavior. For this client, it may not be the drudgery of exercise holding him or her back, but the comfort of a nighttime routine he or she is not yet ready to relinquish.

Exploring the drivers of your client’s behavior can illuminate unmet emotional needs. While addressing these needs is outside your scope of practice as a health coach or exercise professional, this process can help your client recognize and attend to his or her emotional needs. Only when the needs fueling an unhealthy behavior are known and met can a sustainable replacement behavior persist.

To promote this exploration, encourage your clients to ask two questions when reflecting on past behaviors they wish to avoid: What am I (or was I) feeling, and what do I need? This allows them to recognize their unmet needs and develop a catalogue of strategies with which to address these needs.

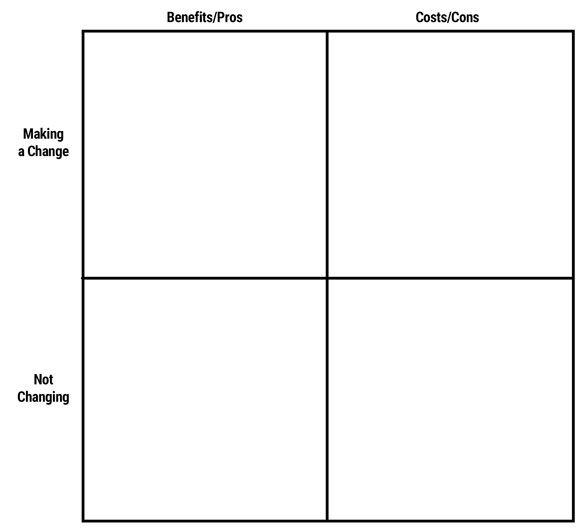

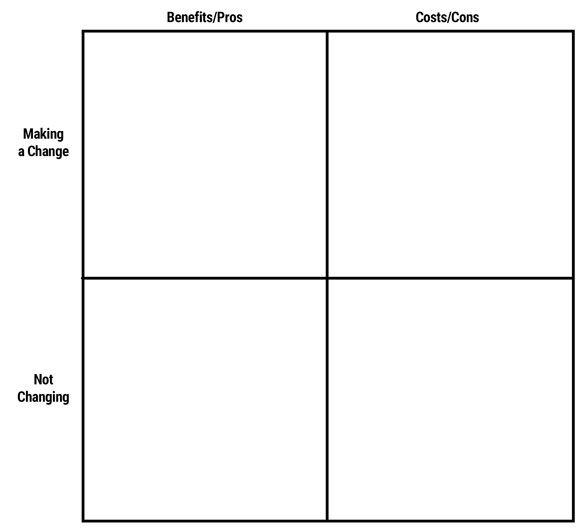

One of the core constructs of the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change (Figure 1), a behavior-change theory that suggests that clients move through defined stages of change, is decisional balance (Figure 2). This process involves the exploration of the pros and cons of both changing and not changing a behavior. For example, a client who wishes to quit eating fast food for lunch and instead bring home-cooked leftovers would explore both the benefits and costs of eating fast food as well as the benefits and costs of bringing food from home. This allows the client to deepen his or her understanding of current behaviors and to determine if his or her ideal plan is feasible. This clarity helps clients choose the most appropriate action plans for their goals, habits and lifestyle.

Figure 1: Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change

Figure 2: Decisional Balance Worksheet

Meet Your Clients at Their Level

In her book, Daring Greatly, shame, courage and vulnerability researcher Brené Brown writes, “Vulnerability begets vulnerability. Courage is contagious.” Brown’s phrase is the synthesis of her years of research—that one person’s vulnerability encourages that of another, and that this vulnerability can help foster connection and act as a catalyst for change.

This philosophy can be applied to your clients. By appropriately sharing your own struggles, you encourage your clients to be open and honest with theirs. If it feels uncomfortable or inappropriate to self-disclose, an alternate strategy is to share similar tribulations and triumphs of other clients, with their permission.

Ultimately, the process of health coaching involves meeting your clients wherever they are to guide and support them toward healthy change. This often requires dismantling fears, questioning self-doubt, offering encouragement and praise, framing failure as a learning experience and digging into their deeper wants, needs and motivations. By creating a safe space for change, you allow this process to unfold, moving clients toward the healthy behaviors and outcomes they desire.

References

AbuSabha, R. and Achterberg, C. (1997). Review of self-efficacy and locus of control for nutrition- and health-related behavior. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 97, 10, 1122–1132.

Artino, A.R. (2012). Academic self-efficacy: From educational theory to instructional practice. Perspectives on Medical Education, 1, 2, 76–85.

Csillik, A. (2013). Understanding motivational interviewing effectiveness: Contributions from Rogers’ client-centered approach. The Humanistic Psychologist, 41, 4, 350-363.

McAuley, E. and Blissmer, B. (2000). Self-efficacy determinants and consequences of physical activity. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 28, 2, 85–88.

by

by